I meant to observe this website's 10th anniversary in 2021, but the Covid pandemic seemed to put the kibosh on that for a number of reasons. If you have time, feel free to browse the six tabs or pages by clicking on the links below. Each one sports a new look and updated information.

Home

Books

Journals

Blog

Photos (Scroll down to view new photos 2019-2023)

Podcasts

Thanks for helping me celebrate 12 years online! RJ

|

0 Comments

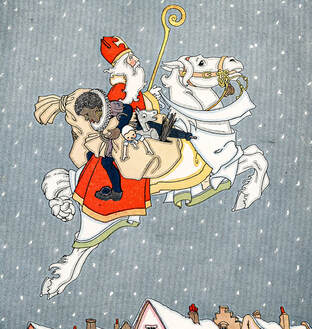

My Book World Miller, Olive Beaupré, ed. With illustrations by Maud and Miska Petersham. Tales Told in Holland. Chicago: Book House for Children, 1926. My paternal grandparents immigrated from the Netherlands over a hundred years ago. My father spoke only a little Dutch and visited Holland once. I, a nonspeaker, have been there twice. I’ve always been fascinated with the culture of this tiny country that would fit nearly two times inside the Texas Panhandle where I live, yet its rich cultural history makes it seem larger than life: Hans Brinker; or, the Silver Skates: A Story of Life in Holland is just one fine example. I’m not sure where my parents found this book, but it has been on our family shelves for a long time, I having absconded with it when my parents were no more. And until now, I’m not sure I’ve ever read it, or had it read to me. There are little crayon marks my late sister made when she was little, and it sat on her shelf. The illustrations are quaint and in that sense make it a children’s book. However, some of the tales are a bit gruesome, and some broach the blunt side of history and politics, making it a book for everyone, I should think. One tale that has always intrigued me is “The St. Nicholas Legend,” which begins like this: “Every winter the good old bishop, St. Nicholas, comes in his ship over the sea from Spain. And who is that with him? It is his servant, a little Moor, named Black Pete[r]. They are bringing goodies and toys for the children of Holland” (88). This tale also connects the Netherlands with its Spanish roots, having been subjected for a time to Spain (as well as France): Look, yonder comes the schooner, When I heard this story as a child—it is simply too hard to be good all the time—I fully expected to wake up one Christmas morning and find in my stocking (one year it was a wooden shoe) a switch. Maybe that is where my parents departed from the Old World traditions, and I am glad.

NEXT FRIDAY: My Book World | TBD

Bailey, Blake. A Tragic Honesty: The Life and Work of Richard Yates. New York: Picador, 2003. Tragedy is a horrendous thing for any human to endure, and yet we all do endure it to one extent or another: adverse childhood experiences, deaths, career failures, and more. The author of this exhaustive literary biography, Blake Bailey, does not employ the word lightly, neither in the title nor how he uses it throughout the book. Bailey’s subject, novelist Richard Yates, born in 1926, has about as tragic life as one can live, yet Yates uses it to formulate his fiction with a high degree of success, perhaps too well, to listen to some critics, many of whom are put off by his lack of “happy endings” or his “dim view” of humanity. No matter what, Yates comes by his viewpoint honestly. In short, his parents’ divorce, not to mention he is raised by a mother who probably has a better opinion of herself than her real talents manifest themselves in her life. She believes herself to be an “artist,” and because of her opinion, her two children (Richard and sister Ruth) are always at the bottom of her priorities. On the other hand, she is a highly seductive person, among other things, encouraging her young son to sleep in her bed. On nights that she stays out late or all night, the boy child lies in bed, wondering where she is. And when she comes home and falls in next to him and vomits on his pillow, his rage is stoked in a way that remains with him his entire life. Some nuggets: “. . . he fixed on his round eyes and plump lips as physiognomic signs of weakness; more to the point, he thought they made him look feminine, ‘bubbly,’ and he had a lifelong horror of being perceived as homosexual” (39). Hm, I wonder why, with the mother thing he has going on. Anyone wanting to get inside the head of one of the greatest American twentieth-century novelists must consider reading this book. It’s that great. My second-hand copy is marked with a “WITHDRAWN” stamp from the Mishawaka-Penn-Harris Public Library in Indiana. Guess it wasn’t much of a hit there.

NEXT FRIDAY: Michael Waldman's The Fight to Vote

My Book World Arenas, Reinaldo. The Assault. Translated from the Spanish by Andrew Hurley. New York: Penguin, 1994. Think Animal Farm meets Nineteen Eighty-Four. Arenas creates his own biting satire of what life is like for Cubans, homosexuals in particular, in Castro’s Communist Cuba. Rather than recreating this hell realistically (as he does in Before Night Falls), Arenas limns a dystopian animal world in which the narrator—a hardline, hateful, and clawed beast—searches out his mother so that he can kill her. He also orders that any man (or woman) who dares to stare at an attired male animal’s crotch (even for a microsecond, as if one might discern such a move) will be annihilated. This cruelty is so absurd as to be laughable in a manner it would not be if portrayed realistically. I’m issuing no spoiler alert (oh, I guess this is it): narrator searches and searches for his wicked mother whom he hates with all his might, to no avail. Meantime, for his fine work killing queers, he is awarded one of the highest honors to be bestowed by the Represident. The narrator is shocked to learn that this represident is none other than his mother! He obtains a raging erection which is not allayed until he porks (to put it nicely) his own mother, she explodes into a million bits, and the narrator’s rage is finally released (ew). Ah, now that’s a climax: Killing queers and the Oedipal impulse all in one go. NEXT FRIDAY: My Book World | Joseph Epstein's Stories Fabulous Small Jews

My Book World Fallada, Hans. Every Man Dies Alone. Translated by Michael Hofmann, with an afterword by Geoff Wilkes. New York: Melville, 2009 (1947). This novel, originally published in German in 1947, is the fictionalized story of a true-life married couple who denounce the Nazi regime. The couple are solid followers of Hitler until their only son is killed in battle. They then turn their anger outward in a quiet manner by handwriting postcards of denunciation which they deposit all over the city of Berlin. They carry on for over two years, placing nearly 300 cards without notice. Yet their campaign is basically a failure because most people who find the cards turn them into the Gestapo so that they do not themselves wind up in trouble. Due to a bit of carelessness, the couple are caught and wind up in prison. Fallada deftly portrays their ending as fearful but brave souls who have no problem talking back to prison officials. Fallada concludes the novel on a positive note by bringing back into view a boy who, because of his terrible home life, has begun a life of crime until he is adopted by a caring and loving couple who help to change his ways. Fallada’s writing is very nineteenth century by way of its omniscient point-of-view in which we know what every character is thinking. He is also quite skilled in creating a large number of characters, yet giving the reader periodic hints about who is whom, thus keeping the narrative moving. Finally, he, from time to time, repeats or skillfully echoes his title, Every Man Dies Alone, in ways that expand its obvious or concrete meaning. Fallada’s novel is a keen reminder that freedom requires sacrifice, that no matter what culture we live in, we must always be on guard against its being taken away from us, or worse yet, that we hand it over without question. NEXT FRIDAY: My Book World | Reinaldo Arenas's Novel The Assault

My Book WorldMaugham, W. Somerset. Of Human Bondage. New York: Doubleday, 1936. “It sings, it has color. It has rapture. In viewing it one finds nothing to criticize or regret.” —Theodore Dreiser The blurb above appears on the dust jacket edition of the novel I read. In its foreword, the author explains, in part, why he writes the novel: “I began once more to be obsessed by the teeming memories of my past life. They came back to me so pressingly, in my sleep, on my walks, at rehearsals, at parties, they became such a burden to me, that I made up my mind there was only one way to be free of them and that was to write them all down in a book” (iv)  My central response to the novel is that, knowing Maugham divorces his wife and lives in a domestic setting with two different men, I believe the book is the perfect portrayal of a closeted homosexual or bisexual male. Like many Englishmen of his period, Philip Carey attends all-boy schools, and Maugham describes some of these young men in lustrous detail, whereas his descriptions of females are not as pointed or glowing. Carey’s relationships with women are fraught with one of two modes. The woman, such as his mother or his aunt, is motherly and nurturing or she, like two women he becomes involved with romantically, are not nurturing. In fact, one, Mildred (portrayed by Bette Davis in the 1934 film), tests the limits of credulity. Yet, when aligned with the profile of a closet homosexual (trying hard to fit into heterosexual life), may be quite accurate. Philip is convinced he loves Mildred and rejoins with her several times after she rejects him, and, except for the final fling, always takes her back no matter how cruel she has been, in one instance, wrecking his apartment and destroying all of his valuables, including paintings he has made or bought. This character knows, even if he has carnal relationships with women, he should not get married. “In Paris he had come by the opinion that marriage was a ridiculous institution of the philistines” (276). When he finishes medical school, he wants to travel, see the world. He only chooses to marry on the last page of the book, when, at last, he has matured and realizes he must settle down. One other observation about the novel I would make is that, in contrast to how fiction writers have worked for the last fifty years, Maugham tells a great deal more than he shows. He spends many, many pages, sometimes, foreshortening a long period of time or era in Philip’s life. Of course, as a playwright, his dialog is on the mark and believable, and the characters do act out some of their emotions, but many times Maugham takes the short-cut of telling the reader how the characters feel. Yet, I do have to say that Maugham does manage to hold my attention for over five hundred pages, and that is saying a lot. NEXT FRIDAY: My Book World | TBD Because I am needed to care for a loved one following his surgery, I am suspending my blog activity, hopefully for no more than several months. Also, I MUST finish writing a book I've been working on for over three years. When I've achieved those two things, I'll return to posting three or four times a week. Until then, please feel free to browse through my archives located to the far right. Below you can find links to a few of my favorite posts from the past year. RJ Sally Field's Memoir Is Powerful Thanks for stopping by . . . until we meet again, keep reading!

My Book World Weinman, Sarah. The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel That Scandalized the World. New York: HarperCollins, 2018. Weinman takes two narratives—one, the actual kidnapping case of Sally Horner, in 1948, and two, author Vladimir Nabokov’s shaping of his 1950 novel, Lolita—and weaves them into a single, seamless story. About halfway through the Weinman’s book, Sally Horner is rescued by the FBI and returned to her mother. Two years later, Sally dies, at fifteen, in a car accident, and I wonder, In what direction could the author possibly now take this book? All along, Weinman has woven the saga of how Nabokov writes Lolita with the story of Sally Horner, providing textual proof by way of his notecards and other documents that Nabokov was indeed influenced by Horner’s story. To what degree foments a debate between Nabokov and the literati that Weinman covers extensively. She also develops the idea that Nabokov has long been fascinated by the narrative of pedophiles and the children to whom they are attracted; in Lolita he finally produces the right combination of elements, one of which is the deployment of an unreliable narrator to steer the reader away from what a sinister crime he is actually participating in. Weinman skillfully stitches together these two narratives and provides a long, relaxed denouement tying up all the loose ends: relatives affected by Sally’s premature death, the imprisonment of her captor, a discussion of the abuse of young girls and women, and more. Because of her unrelenting research and attention paid to detail, Weinman provides a satisfying read combining the genre of true crime with serious literary discussion of Nabokov’s novel. It is one of the few books I’ve read this year that I have not been able to put down once started. It’s that good. NEXT TIME: My Journey of States-31 South Carolina

My Book World Ginna, Peter, ed. What Editors Do: The Art, Craft, and Business of Book Editing. Chicago: U of Chicago, 2017. Ginna has amassed a large number of essays by editors and agents, or those who used to be one or the other. He organizes their pieces around broad topics such as acquisition, editing process, and publication. But he also includes a section concerning memoir and one about careers in publishing. Writers have heard ad infinitum what editors want when they attend workshops, but somehow, when one is suddenly on the other side of the desk peering through the eyes of those editors one begins to understand. One begins to change how one might structure one’s book or write a book proposal. One suddenly sees what is important. One sees what editors do not want to see. I found three essays to be particularly helpful to me, but I imagine that each reader of this book may find others more attractive precisely because they have different priorities than I do. 1. “The Other Side of the Desk: What I learned about Editing These essays are ones that I shall refer to again and again as I attempt to maintain a writing and a publishing life. Perhaps the reader might like them, as well.

NEXT TIME: My Journey of States-29 Hawaii

My Book World  Pam H., R. Jespers, K. Dixon, 2005, Taos Pam H., R. Jespers, K. Dixon, 2005, Taos I first heard Pam Houston speak in 2000 when she gave a reading for her new book, Waltzing the Cat. As she addressed a sizeable audience, and, as I met her afterward at a reception I told myself if I ever got a chance to take one of her workshops I would. I managed three: Taos, 2004 and 2005; I even journeyed to Mallorca, Spain to study with her. I didn’t do so as a groupie necessarily (though I am); it took me three different week-longers to digest her method for creating fiction—a method that resonated with me, using one’s own life and one’s own observations to create narrative. I’ve always admired Houston’s ability to transform intensely autobiographical information into strong fiction. Some writers refuse to touch such material; others wallow in their biographies like dogs in the dust, trying but failing to rid themselves of their demon fleas. Pam has been the most influential contemporary writer, in that respect, on my thinking about writing. She taught me how to transform my autobiographical material, or perhaps she taught me to give myself permission to do so because by being that honest writers can hurt someone they love or even people they don’t. And you have to balance your honesty against how much you value the relationship, and honesty doesn’t always lose out. Anyway . . . I feel that I was in on the inception of Contents, as well as several of its chapters because during class or at a meal, Pam would share an anecdote that eventually wound up in this novel. In 2008, at a Point Reyes bookstore, I heard her read one of the book’s short chapters-in-progress. At the time, she planned, I think, to write 144 of those chapters giving voice to the many hundreds of trips she had taken around the world, the hundreds of places she had visited in the States, the myriad human beings who had influenced her life. Why 144? “I have always, for some reason, thought in twelves” (308), Pam declares in the very last section of her book, the “Reading Group Guide.” She ends up with 132 chapters and 12 airplane stories, but still, I think she delivers on her original plan. The novel feels very global, in its fast-paced, jet-flight episodes knitted together like bones on the mend. How else could she portray a trip around the world, one which may never end as long as she lives? Both Pam-the-person and Pam-the-author nearly lose their lives as four-year-olds when their fathers seriously abuse them, and their mothers cover up the story, amuse themselves through retelling it over cocktails, falsehoods about her pulling large pieces of furniture over on top of herself. Nearly losing their lives gives both Pams permission to push their lives to the limits because otherwise they might not be worth living. Planes that almost fall out of the sky. Boyfriends who don’t work out. Bedeviled by chronic pain since the childhood accident. . . neither Pam is comfortable unless her contents have shifted a bit since her last outing. She must be on the move, searching for that next glimmering glimpse of life, whether it is of a Tibetan monk or the life of a child whom she helping to raise. She must move. Such a novel reflects the life that Pam lives, right? In any given year, Pam-the-author is equally at home on her ranch in Colorado, which she purchased after the phenomenal success of her first book, Cowboys Are My Weakness, equally at home on campus, equally at home teaching scores of workshops or giving readings, equally at home traveling to remote parts of the world to test her physical or emotional strength, equally at home revealing the parental abuse she was subject to as a child, lovers who have betrayed her. In this book, in particular, she manages to transform the latter three issues into a gross of clipped chapters, in which Pam-the-character (in the manner of Christopher Isherwood naming his protagonist Herr Issywoo after himself) makes herself at home on flights to Exhuma in the Bahamas, to places as obscure as Ozona, Texas. Tibet. New Zealand. Paris. Chapters named with a flight number: UA #368. Your life, as long as you are reading this book, is as discombobulated as Pam-the-character’s. You live it with her, the flashback in which Pam-the-character is hospitalized for injuries caused by her abusive father. Pam Houston—the author—gives her all to every minute that she lives, I would suspect, even when she is lying very still, devouring the pages of a new book or romping with her Irish wolfhounds through the meadowlands of her ranch. As long as she is breathing, she is inhaling the content of her next book, itself spinning inside her brain while all she seems to do is become a vessel for it, channeling the narrative burning inside her at that moment. That is what Contents May Have Shifted is about. After having been moved and enlightened by her first four books, I can now say the same for this one. And Pam Houston’s new tome, Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country, comes out January 29, 2019. You’d better believe I’ve already ordered it, that I can’t wait to begin feasting on her pages once more. You see, I’m still learning from Pam. NEXT TIME: My Journey of States-23 Tennessee

My Book World Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. With a new introduction by the author. New York: Anchor, 2017. I suppose I always felt this book, originally published in 1986, was a woman’s book—chick lit—but after viewing the MGM/Hulu production of Atwood’s novel, I believe I was wrong. A dystopian world in which women are nothing more than baby makers and terribly devalued if they cannot deliver is not a world any of us want to live in. Such a world is also one in which all human beings are devalued, consigned to rigid gender and social roles. Atwood herself may articulate the novel’s greatest value in her new introduction: “But there’s a literary form I haven’t mentioned yet: the literature of witness. Offred records her story as best she can; then she hides it, trusting that it may be discovered later, by someone who is free to understand it and share it. This is an act of hope: every recorded story implies a future reader. Robinson Crusoe keeps a journal. So did Samuel Pepys, in which he chronicled the Great Fire of London. So did many who lived during the Black Death, although their accounts often stop abruptly. So did Roméo Dallaire, who chronicled both the Rwandan genocide and the world’s indifference to it. So did Anne Frank, hidden in her secret annex” (xviii). Indeed. A novel in which almost half of the chapters are entitled “Night”—and are alternated with ones like “Jezebel’s” and “Salvaging”—readers should be duly warned that we, too, could descend into a world of moral darkness, that we should take heed from this, our literature of witness.

NEXT TIME: My Journey of States-20 Florida

My Book World St. Aubyn, Edward. Patrick Melrose. New York: Picador, 2015. I more often read a novel before viewing a film version, but less often do I read the novel after tuning into something like, say, Showtime’s “five-part limited series,” of the same title. It is one of those series which may have been equal to the book, or books, because Patrick Melrose is a compendium of St. Aubyn’s five novels about the same character, and it unfolds almost as luxuriously as the book. Patrick Melrose may be one of the best contemporary novels to come to grips with the life of a drug addict. But more important, I believe St. Aubyn traces the aspect of abuse within a family over several generations, and how, unaddressed, it can devastate a family—wealthy or not. Substance abuse is merely a symptom of the deeper problems buried in the Melrose family history. Patrick Melrose, born in 1960, approximately the same time as his creator, experiences physical abuse when his father perpetrates sodomy on him at an early age—repeatedly over several years. But then there is also the emotional abuse, when Patrick’s father, David, swears Patrick to secrecy or he will be “very severely punished” (79). (In the film, he says he will snap him like a twig.) Patrick’s mother? Well, her abuse of him manifests itself as ignorance—blissful, willful ignorance of how David is treating their son. She, too, has suffered abuse as a child and at the hands of her husband, and they, without even trying, do their best to destroy Patrick’s life. What is most remarkable about this novel is that St. Aubyn manages to limn the skeletal remains of the several generations of this family without any shortcuts or platitudes. On the next to the last pages of the book, Patrick has earned the profound conclusions at which he arrives: “He imagined himself as the little boy he had been at that time, shattered and mad at heart, but with a ferocious, heroic persona, which had eventually stopped his father’s abuses with a single determined refusal. He knew that if he was going to understand the chaos that was invading him, he would have to renounce the protection of that fragile hero, just as he had to renounce the illusion of his mother’s protection by acknowledging that his parents had been collaborators as well as antagonists” (855-6). My God, in a nutshell, the entire novel portrays the unraveling of this moneyed British family, their accumulated abuses and how they lead to “drug and alcohol abuse” by Patrick, his chosen method of coping. Cause and effect, folks. Cause and effect.

I have only a couple of observations which might manifest themselves as criticisms: In spite of St. Aubyn’s lyrical and commanding prose, sustained over nearly nine hundred pages, I was often distracted. First, he participates in what American workshoppers call head-hopping, that is, employing the third-person omniscient point of view, not commonly used since the nineteenth century. Yet, I must probably applaud him because he manages to employ it with great skill, and, in a novel of this breadth, it is amusing and strategically important for the reader to know exactly what each character is thinking at any given time. And two, the author uses, repeatedly, speech attributions which seem inappropriate or awkward. What do I mean? Any speech attribution, to my way of thinking, ought to be a synonym for the word “said,” or “spoke”: “declared,” “replied,” or similar verbs. Not so here: “The daughter is impossible,” grinned Laura (408). “Grin” is not a synonym for “said,” and it gives the sentence an amateurish patina. I wonder: Is this an acceptable practice in the writing of fiction within the United Kingdom? I should hope not. Another scathing example: “You may well ask,” scowled Nicholas (704). Seriously? How is “scowling” like “speaking?” This questionable practice is rife throughout the novel, marring what is otherwise impeccable prose, and could have been nipped in the bud by a good editor. Please help me to understand, Mr. St. Aubyn. Why would you do this to your book? NEXT TIME: Final Installment of Defeating A Fib At Last

My Book World Aciman, André. Call Me by Your Name. New York: Farrar, 2007. This novel is a romance, both with a capital “r,” the kind that emphasizes subjectivity of the individual, and the small “r” kind, the Harlequin type that you must devour page by page, word by word, until you come to the final sentence of this desperate love affair between two young men. I found the first half tediously slow. But then I thought, Aciman must want us to be inside the head of the protagonist narrator, Elio. These are the mind and heart of a seventeen-year-old boy who can’t decide who he is whether it’s with regard to sexual orientation or his prodigious musicianship (he transcribes manuscripts from one instrument to another and sells them). His mind belabors everything including the appearance of a young graduate student, Oliver, who comes to live in his family’s Italian villa for the summer of 1983, a tradition Elio’s father, a professor, has begun years before: the summer intern. Both Elio and Oliver waste half the summer semi-rejecting one another, making love to girls, until finally Elio becomes more aggressive and discovers Oliver has wanted him since they first met. Their first kiss doesn’t occur until page 81. But for a short, intense two weeks they become so close that they almost become one, wearing each other’s clothing, Elio especially in love with a red swim suit of Oliver’s. The very idea of calling each other by their own names—taking the name your parents have given you and calling your lover by that name—is a mental flip the reader must make to understand the depth of their intimacy: “Perhaps the physical and the metaphorical meanings are clumsy ways of understanding what happens when two beings need, not just to be close together, but to become so totally ductile that each becomes the other. To be who I am because of you. To be who he was because of me. To be in his mouth while he was in mine and no longer know whose it was, his cock or mine, that was in my mouth” (142-3). Aciman carries the development of this intimacy, which in the form of a deep friendship is to last forever, to the very last sentence of the book: “If you remember everything, I wanted to say, and if you are really like me, then before you leave tomorrow, or when you’re just ready to shut the door of the taxi and have already said goodbye to everyone else and there’s not a thing left to say in this life, then, just this once, turn to me, even in jest, or as an afterthought, which would have meant everything to me when we were together, and, as you did back then, look me in the face, hold my gaze, and call me by your name” (248). Through the specificity of this scenario, Aciman reveals a universal story of desire and love. We’ve all been there, and wow, should our lives turn out as exciting as those of the two men characterized in this romance.

NEXT TIME: My Literary World

My World of Short Fiction January/February 2018, David Greendonner. “Lionel, for Worse”: This story, winner of the Kenyon Review Short Fiction 2017 competition, is a gem of understatement. Narrated by a woman, she tells of her husband, Lionel, who a month earlier has lost his best friend, Stan. The woman and Lionel discuss how they’d like to have their ashes disposed of someday. While making a trial run on the shore of Lake Michigan of just such a disposition, using ashes from their own hearth, they encounter some high school girls, one of whom says, “I’m so sorry for your loss” (5). The line is both humorous and subtly poignant concerning the man’s true loss. Profile of author from contributor’s page: "David Greendonner is from Bridgman, Michigan, and is a graduate of Western Michigan University’s MFA program in fiction. From 2015 to 2017 he was the managing editor of the literary magazine Third Coast" (115). NEXT TIME: My Journey of States | 2-Oklahoma

New Yorker Fiction 2017***—Excellent **June 26, 2017, William Trevor, “The Piano Teacher’s Pupil”: Compression is the primary gift of this story in which a woman, Elizabeth Nightingale, takes on a new young pupil whose genius she detects immediately. ¶ Soon after, following each boy’s lesson, Nightingale notices that little items begin to disappear: a snuff box, a porcelain swan, an earring, among a host of others. The thefts compel her to recall others more significant: the sixteen years she has given to a lover who would not leave his wife, the life she sacrifices for her father because he has given his to her. A master can break all the rules—no dialogue, perhaps too much exposition or telling—but Trevor does so with impeccable taste and grace. By story’s end we both adore and pity Miss Nightingale.

NEXT TIME: My Book World

New Yorker Fiction 2017***—Excellent  Carlos Javier Ortiz Carlos Javier Ortiz ***June 5 and 12, 2017, Will Mackin, “Crossing the River No Name”: Some Navy seals in Afghanistan, in 2009, set out to ambush a group of Taliban. ¶ In this rich story the narrator relates two flashbacks, one rather lengthy, which seamlessly portray the complexities of wars and those intrepid souls who fight them. The author creates character more by interior shots and with zingy names such as Hugs and Cooker than by things visual. He creates character when the narrator encounters a vision of the Virgin Mary in a near-drowning situation. The narrative’s climax may occur when Hal, the Big Kahuna, disappears beneath the surface of a river that appears on no map, that virtually disappears in different seasons. Is Hal alive or not? The narrator apparently does not know because even though Hal is his best pal, he must carry out a mission of war. This story—with its rich imagery and figurative language—is the sort I love most, one that carries me into a world I would never encounter first-hand, nor want to, but with great skill Mr. Mackin snatches me up and returns me safely to my seat when he has finished with me. If I were awarding four stars it would receive five. The author’s debut collection, which I can’t wait to read, will come out in March 2018. Photograph by Carlos Javier Ortiz. NEXT TIME: New Yorker Summer Fiction Issue 2017

New Yorker Fiction 2017***—Excellent  Ben Newman Ben Newman ***May 29, 2017, Samanta Schweblin, “The Size of Things”: Enrique, a wealthy young man who lives with his mother, is abruptly cast aside and begins to live in a toy shop he often patronizes. ¶ For his keep he reorganizes the store for the owner, arranging toys by color instead of type. Business booms! The author seems to withhold as much as she reveals about Enrique. Why has he been kicked out by his mother? Why is he so child-like? Why are his unconventional methods so successful? Readers only know what the store owner knows, and though an omission of detail would normally be a storytelling sin, it seems to work here. It allows me to imagine. The author’s book, Fever Dream, recently came out in English. Illustration by Ben Newman NEXT TIME: My Book World

MY BOOK WORLD Whitehead, Colson. The Underground Railroad. New York: Doubleday, 2016. The tight structure of this novel is based on twelve chapters—six named for characters and six named for states or regions in the US. Each one shifts readers to where they need to be to follow the life of a runaway slave, Cora, in the pre-Civil War South. Cora’s grandmother, Ajarry, was a slave, and so was her mother, Mabel, who abandons Cora when she’s eleven. Rage governs Cora’s life, fuels her temper and her senses, both of which serve to save her life as she shapeshifts to fit varying situations above ground. The unsuspecting reader who learned in elementary school that Harriet Tubman’s underground railroad was not literal is in for a fantastical ride as Whitehead brings it alive, with stations and steam engines and schedules, even a pump handcar that serves as Cora’s final vehicle of escape. The author’s grasp of history, his simple yet elegant prose, and his understanding of the complex humanity of master and slave serve to create a novel that is worthy of all the praise and accolades it has received. NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2017

My Book World Furbank, P.N. E. M. Forster: A Life. New York: Harcourt, 1977. After reading Christopher Isherwood’s entire oeuvre in 2015-6 and seeing what an influence Forster had been on the man, I felt compelled to read this Forster biography, as well. Isherwood credits Forster with, among other things, providing him with a creative mantra: Get on with your own work; behave as if you were immortal. Isherwood reminds himself, page after page in his journals, that he must remain industrious. Since Furbank does not provide a complete list of Forster’s titles but offers them up in the narrative (and index) instead, it is difficult to realize that Forster, too, produced a broad variety of works, well over twenty. So, a generation apart, Forster provides the model for Isherwood’s ethic. They seem to share similar ideas on literary quality, standards, a certain fussiness in regard to everything. Yet there exist differences between the two men born a generation apart. Forster, though he does write about sex between men, does not allow it to be seen, particularly Maurice (which is written in 1913-4 but published posthumously in 1971 and made into an Ivory-Merchant film, in 1987) until after his death. Though he becomes sexually active with men at one point, it is not to the degree, I believe, that Isherwood does, the latter claiming to have had over four hundred partners, and yet sharing his last thirty-three years with one man. Forster is never able to find that one man, though I believe he would have liked to. He did have close emotional relationships with other men, but they were mostly married, and in no way did he wish to interfere with those, or gay friends to whom he was not physically attracted, such as his peer, J. R. Ackerley. Isherwood made a break with British culture by making his home in America in 1938-9. Though well-traveled throughout the world, and though he empathized with a great many others, Forster’s being was too deeply rooted in Britain ever to leave. Just the story of the home he lived in with his mother for so many years is enough to complete this picture. When finally vacating West Hackhurst, a rather large estate, it takes the man many months to categorize all the collections of things that had come down to him, and, that as an only child, he now must be rid of: decades, if not centuries, of useless family letters and documents, furniture, clothing, carpets, dishes, art. Nuggets: Personal writing of Forster, in which he goads himself to improve his lot: Furbank’s biography combines two volumes with separate pagination, totaling over six hundred pages, a slog of a reading but well worth the time if one is interested in how a particular author writes, his opinions, his family, his friends and lovers. If one is searching for, as Isherwood does, a literary hero, E. M. Forster possesses a generosity of spirit that, dead or alive, is difficult for one to reject.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2017

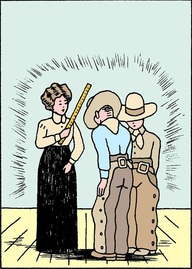

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Alain Pilon Alain Pilon November 28, 2016, Robert Coover, “The Hanging of the Schoolmarm”: In some iteration of the Old West, a schoolmarm closes down a saloon by winning it in a card game. ¶ One supposes that this short short story is a satire of our civilization in general. Schoolmarm rules the roost until the sheriff usurps her power and condemns her to hanging. She is a brave one, claiming that self pity “is the lowest state to which a person’s mind can fall” (81). One wonders if schoolmarm isn’t a mouthpiece for Coover: “A landscape of rocks evokes a time before time, and the end-times as well, forcing us, while contemplating it, to live in all time at once, where words have nothing to attach themselves to” (81). Is this old man’s story deliberately attributed to two-dimensional characters, or is it an example of philosophic sophistication that one admires? The reader must judge the schoolmarm’s words: “‘That is what rocks express. Though they are otherwise meaningless, they are, in this respect, the most meaningful thing we have, putting us in touch with oblivion. Which is the ineffablest thing of all’” (81). Coover, eighty-four, not even listed in the Contributors for this issue, has a novel coming out in January: Huck Out West. Illustration by Alain Pilon.  READ MY ‘BEHIND THE BOOK’ BLOG SERIES for My Long-Playing Records & Other Stories. In these posts I speak of the creative process I use to write each story. Buy a copy here! At new prices. Paper: $10.75 | £7.75 | €8.50 Kindle: $2.99 Introduction to My Long-Playing Records "My Long-Playing Records" — The Story "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "Ghost Riders" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Blight" "A Gambler's Debt" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Engineer" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "The Age I Am Now" "Bathed in Pink" Listen to My Long-Playing Records Podcasts: "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "My Long-Playing Records" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "Bathed in Pink" Also available on iTunes.

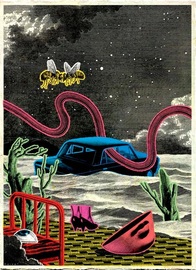

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Chloé Poizat Chloé Poizat October 31 2016, Anne Carson, “Back the Way You Went”: This sparse story is divided into three parts, each, it would seem, tangentially or even obscurely related to the other. ¶ In “Garland,” a woman recovering from loss becomes a bee as her two bee friends, later divorcing, attempt to ease her pain. In “Mexico,” a woman and her elderly mother visit her father, an Alzheimer’s patient, in the facility she refers to as the Last Lap. “Trouble in Paradise,” written in first person from an adult daughter’s point of view, highlights a quiet Christmas she spends with her mother-in-law in Ohio. She ends their dishwashing conversation by saying she’s brought a recording of Lubitsch, presumably a silent film by the German director, known for his avant-garde style. This reference, like Carson’s allusion to Gogol, perfectly suits this story which seems to exist outside of any conventional sense of time. Carson’s second New Yorker story in 2016. Her collection, Float, is out now. Illustrated by Chloé Poizat NEXT TIME: My Book World

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Andrew B. Myers Andrew B. Myers October 3, 2016, Etgar Keret, “To the Moon and Back”: A young Israeli father buys a multicopter drone for his six-year-old son and presents it to him the day after his birthday. ¶ Why? Because he’s divorced, and the mother never allows this father to be present on the kid’s birthday. On this day after, this father take his kid to the mall to get batteries for the drone remote, and at some point a cash register becomes a point of contention when the boy, Lidor, wants that for his birthday present—simply because Daddy has said he can have anything in the store as his second present. Later, having given up on the cash register purchase (offering 2,000 shekels), the father and his son fly the drone at the park. The father cajoles his Lidor: “Who loves Lidor the most in the world?” I ask, and Lidor answers, “Daddy!” This story both irritates and delights. You absolutely hate that this father has to perform acrobatics to see his kid and get him to love him, but you love the fact that the father’s willing to perform such acrobatics in order to hear that “killer laugh of his. There’s nothing nicer in this stinking world than the sound of a kid laughing” (65).  READ MY ‘BEHIND THE BOOK’ BLOG SERIES for My Long-Playing Records & Other Stories. In these posts I speak of the creative process I use to write each story. Buy a copy here! Introduction to My Long-Playing Records "My Long-Playing Records" — The Story "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "Ghost Riders" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Blight" "A Gambler's Debt" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Engineer" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "The Age I Am Now" "Bathed in Pink" Listen to My Long-Playing Records Podcasts: "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "My Long-Playing Records" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "Bathed in Pink" Also available on iTunes. A WRITER'S WIT Hot Time in Tucson  Pacaud/Roberts/Shere Pacaud/Roberts/Shere September 22, 2014, Victor Lodato, “Jack, July”: Jack, twenty-two, of Tucson, is a meth addict who’s been rejected by his mother, his sister, and girlfriend, Rhonda. ¶ In a way you feel like a voyeur while reading this story, so intensely does Lodato let us in on what it is like to be a crystal meth user. Living fast is what Jack calls it, life speeded up past the speed of sound. You witness Jack’s stink. You witness his thoughts of the past (sister mauled by a dog, a less than competent mother). You feel the searing July 4th heat as Jack negotiates this fast life. You even glide into the fuzzy, foggy world of meth as he returns to the place where he’s flopped for the last two weeks, the only home he has left. His obese roommate pats his kimono pocket, and answers Jack's silent question with “I do I do I do.” Life couldn’t seem any bleaker than this, yet somehow you hope. You hope. Lodato’s novel, Mathilda Savitch, was published in 2010. Illustration by Julien Pacaud. Left: H. Armstrong Roberts. Getty (Dog). Right: Sam Shere. Time Life Pictures / Getty (Man). I WILL MAKE NO MORE POSTS UNTIL AFTER SEPT. 30 | PLEASE PERUSE BLOG ARCHIVES IN RIGHT SIDE BAR. THANKS! A WRITER'S WIT Do It Yourself or Use Company "Services"? It is possible, if you know what you’re doing or if you’re willing to conduct your own on-the-job-training, for you to print a book at Amazon’s CreateSpace for FREE. That’s right! But it means you must also know (or learn) how to manipulate their software once your manuscript is uploaded, to get the fonts you want, positioning text on the page. You must upload your own cover image(s), place them where you want them, select background and font colors and sizes. The final result may be much simpler looking than you would have hoped. But, if your funds are limited and you just want to get a book out there, this might be the route to take.

I would suggest going online to the CreateSpace home page. There you will find six categories. Click on the subheadings to find out more. Also, CS has any number of videos you can view to assist you in every category. I took the path of investing what I think is a reasonable amount of money, largely because I wanted the book to have the best chance possible of having high production values. Having said that, I felt that CS wanted too much money for editing services, given that all my stories had previously been published. Instead, I located someone local, a friend and colleague named Barbara Brannon, to copy edit the final MS for me. Not only had she critiqued a good number of my stories in the writing group I belong to but she had edited more than sixty books in her career as editor and writer, so I felt quite confident in her abilities. And even though all the stories in my collection had been vetted, in a sense, by way of their appearance in nationally recognized literary journals, Barbara still located errors! And there was stylistic consistency, an overall look of the MS, to consider. She also cleaned up the MS by inserting page breaks where appropriate and using a paragraph indention of .4 of an inch instead of the standard tab indention. She prepared the MS to upload for the Kindle app! And she charged me far less than CreateSpace would have, what the local market would bear. Depending on where you live, you too may be able to find a competent editor for less money than CS will charge you. And no matter how fine a writer you are, you will need to find an editor or copy editor. If you go it alone, your eyes may overlook the same homonym error a million times or perhaps that unintended fragment or comma splice. A fine editor will not interfere too much with the content of your work; a fine copy editor will see to it that your copy reads smoothly and in a consistent voice throughout the MS. A fine editor will give you choices when it comes to revising the copy so that it reads well and conveys the meaning you originally intended. CreateSpace offers services to help the writer develop the interior and cover of his or her book. CS also makes available marketing services. Again, I urge you to locate the CS home page online and find out what services it provides. CS also affords you a handy device that allows you to calculate what your royalties might be, thus allowing you to set a reasonable price for your book. Most of all, I believe, self-publishing is about creating a book that represents your sensibilities. The one problem with traditional publishing is that once your MS is purchased, your MS ceases to be yours! NEXT TIME: NEW YORKER FICTION 2014 A WRITER'S WIT My Book World  Macaulay, Rose. The Towers of Trebizond. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. New York, 1956. I came upon Ms. Macaulay when I was searching for a female writer born on August 1 to use in my “Writer’s Wit” citation for that date. The book sounded interesting because according to the woman’s biography, she struggled at times with whether she would live a secular life or a Christian one, and her work reflected such a conversation. The book obviously takes place in Turkey, throughout the Middle East of a much earlier time. And obviously, neither men nor women could easily travel there today. Information I’ve adapted from the back cover tells the plot in a nutshell: The narrator, Laurie, relates the story of herself, her Aunt Dot and camel (whom Laurie borrows from time to time), and Father Hugh Chantry-Pigg. They are traveling from Istanbul to Trebizond to spread Christianity; Laurie is perhaps more devoted than her Aunt Dot, though they both seem to fade in and out on that matter. Along the way this troupe encounters spies, a Greek sorcerer, an ape, and Billy Graham with a busload of evangelists. The novel is part travelogue and part comedy of manners, “a bracing meditation on the perils of love, doubt, faith, and spirituality in the modern world.” This novel is considered by many to be Macaulay’s finest. I found it interesting, but I must confess that it would have been more entertaining had I ever traveled to that part of the world myself . . . and if I’d studied more ancient history; many of the references were lost on me. And I believe her “wit” to be a bit anachronistic, perhaps understandable to the British and/or those who lived as adults at the time she wrote this book. I have the hard copy if anyone should want to borrow it! Let me know. NEXT TIME: DIY PUBLISHING 101-C |

AUTHOR

Richard Jespers is a writer living in Lubbock, Texas, USA. See my profile at Author Central:

http://amazon.com/author/rjespers Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

Blogroll

Websites

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed