FRI: My Book World | Daniel Fitzgerald , Faded Dreams: More Ghost Towns of Kansas

TUES: A Writer's Wit | Ruth Westheimer

WEDS: A Writer's Wit |Margaret Drabble

THURS: A Writer's Wit | Pierre Corneille

|

Up Next:

FRI: My Book World | Daniel Fitzgerald , Faded Dreams: More Ghost Towns of Kansas TUES: A Writer's Wit | Ruth Westheimer WEDS: A Writer's Wit |Margaret Drabble THURS: A Writer's Wit | Pierre Corneille

0 Comments

Coming Next:

THURS: A Writer's Wit | Chinua Achebe FRI: My Book World | Casey McQuiston, Red, White & Royal Blue

FRIDAY: My Book World | Reinaldo Arenas's The Doorman

My Book World Tolstoy, Leo N. What Is Art? Translated from the Russian by Almyer Maude [sic] with an introduction by Vincent Tomas. Indianapolis: Sams, 1960 (1896). I was assigned to read this book for a half-credit, pass-fail humanities class in college. There is little indication that I actually did so (a few underlined passages in Chapter Two). It seems like a challenging read for eighteen-year-olds who’ve had little exposure to argumentation or (unless they have studied art as children) art. In general, to summarize an often unclear thesis, Tolstoy seems to believe that art is a feeling that the artist would like to infect the watcher, listener, reader with. He believes that high art is so only because it is heralded by the upper classes. Tolstoy goes on and on about how bad Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is, in part because Beethoven was deaf, and how could the composer possibly compose if he couldn’t hear? And besides, Beethoven is attempting to combine two arts: music and chorus (based on another’s lyric). Tolstoy abhors contemporary opera, Wagner in particular, again because it combines visual art, drama, music, singing, and more. When he uses the invective “filthy” to describe it, it seems he has a prejudice he can’t explain. In fact, he leaves a lot unexplained by way of sometimes poor or faulty logic, and by using terms he has defined to his own satisfaction. He asserts that beauty is not art. He asserts that the basis of art must be religious, i.e. Christian (I think). However, Tolstoy does make a prescient remark when he argues that art (music, drawing, creative writing and more) should be taught to all children so that they may create art for all their lives, in order to enrich their lives and the lives of the people they love. That seems to be the most positive assertion that he makes, and, because many American school districts have abandoned the teaching of art, the result being a certain poverty, I believe he is right. The rest of this work seems like a highly subjective opinion he took fifteen years to develop; if he’d tried hard he probably could have done it in four or less. NEXT FRIDAY: My Book World | Sayaka Murata's Convenience Store Woman

My Book World Vreeland, Susan. Girl in Hyacinth Blue. New York: Penguin, 1999. In contemporary times, a Philadelphia professor calls a colleague (who is an art scholar) into his locked study to reveal what he claims is an original work of the Dutch artist, Vermeer. The colleague argues against such a claim, but the man insists. He is in a bind because his father has confessed that he himself stole it from a Jewish home while he was working for the Nazis in WWII, but he cannot reveal such indicting provenance. Each succeeding chapter takes the reader farther back in history (à la the film The Red Violin) to reveal previous owners, right up to, the reader must assume, Vermeer himself. All owners are fascinated by the painting and yet must depend on its sale to save themselves or their family from financial disaster. The author explores the value of art. Is it entirely intrinsic, or is it monetary, or is it a bit of both? Vreeland manages to explore this unique idea in a poetic manner which is both compressed, yet expansive, a valuable topic for discussion. The novel is a timeless read, and I’m glad a friend recommended it to me long ago and that I finally took the time to read it. NEXT FRIDAY: My Book World | Alison Smith's Name All the Animals

Dear Fellow Travelers, This first installment of my Barcelona Photographs—made during UMC's Seniors Are Special trip in November—is comprised of as many candid shots I could get of our group of thirty-two. In the coming days I'll also post photographs of the region's architecture and its colorful people. Stay tuned! NEXT TIME: My World of Short Fiction 2018

My book WorldI'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the twenty-third in a series of twenty-four.  Isherwood, Christopher, author, and Don Bachardy, artist. October. Los Angeles: Twelvetrees, 1981. In October of 1979, these two men who were longtime companions produced material for this art book with pages of twelve by nine inches. Isherwood wrote text for each day of the month, and Bachardy produced thirty-two portraits of their friends or associates. The text is not coordinated in any way with the drawings, nor should it be. This is one of print run of 3,000 copies, and much of the text repeats or is a variation on material that Isherwood has already covered in either his diaries or other contemporary books, such as Kathleen and Frank, a memoir of his parents. Nuggets: “The beginning of October is a joyful, hopeful, inspiring time of the year for me—it always has been. For me, born so late in the summer, autumn is my spring. This is the season which I associate with fresh work-projects in their earliest, most creative phase—the phase of discovering what the project is really about, rather than how I can execute it” (8). October is a project the two men designed so that they might work together (although they did also collaborate on a number of scripts). Nonetheless, I enjoyed reading the book and look forward to viewing the drawings again and again.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016 A WRITER'S WIT Reno, Nevada—August 3, 2014 NEXT TIME: NEW YORKER FICTION 2014

A WRITER'S WIT More Antics The photos below are brought to you courtesy of our backyard birdcam by Wingscapes. You can set up the camera in a variety of ways. The most successful way for us has been to prop it up several feet from a small pool. The movement as well as the creature's heat trigger the camera. It has some faults. You can't control the exposure, getting some shots that are underexposed and some that are overexposed. The lens isn't the best. The smaller birds seem to evade its powers, but I think it's a matter of going into the bowels of the camera and changing the settings, which we plan to do soon . . . if we can figure out how. We believe the directions originated in Chinese and then were fed into Google Translate, and we all know how that works. NEXT TIME: NEW YORKER FICTION 2014

A WRITER'S WIT My Book World  Doidge, Norman. The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science. New York: Penguin, 2007. I don’t often read “science” books, but I was tempted away from literature by my partner to read this one. Dr. Doidge, through years of research, proves that the human brain is capable of being rewired, even after being damaged, even in old age! Neuro is for “neuron,” the nerve cells in our brains and nervous systems. Plastic is for “changeable, malleable, modifiable.” At first many of the scientists didn’t dare use the word “neuroplasticity” in their publications, and their peers belittled them for promoting a fanciful notion (xix). One aspect that makes the book fascinating is the number of case studies that Doidge brings to the reader’s attention: people with brain injuries, people born with only the right side of their brain, people with extreme emotional problems resulting from childhood trauma. Doidge contends that with exercise, people can change their brain “maps,” can change their brains. He tells of Arrowsmith, a school that takes these kinds of exercises seriously. The brain exercises are life-transforming. One American graduate told me that when he came to the school at thirteen, his math and reading skills were still at a third-grade level. He had been told after neuropsychological testing at Tufts University that he would never improve . . . after three years at Arrowsmith, he was reading and doing math at a tenth-grade level (41). The concept of brain plasticity helps to explain or reexamine all sorts of problems or phenomena. Language development, for instance, has a critical period that begins in infancy and ends between eight years and puberty. After this critical period closes, a person’s ability to learn a second language without an accent is limited. In fact, second languages learned after the critical period are not processed in the same part of the brain as in the native tongue (52). One of the experts that Doidge studies, Michael Merzenich, continues the line of thinking: If two languages are learned at the same time, during the critical period, both get a foothold. Brain scans . . . show that in a bilingual child all the sounds of its two languages share a single large map, a library of sounds from both languages (60). Merzenich strongly believes that older persons should continue “intensive learning,” that such an activity strengthens our brains. Merzenich thinks our neglect of intensive learning as we age leads the systems in the brain that modulate, regulate, and control plasticity to waste away. In response he has developed brain exercises for age-related cognitive decline—the common decline of memory, thinking, and processing speed (85). Wow! Doidge goes on to say that is why learning a new language in old age is so good for improving the memory generally (87).

To summarize the rest of the book, the author connects brain plasticity with love and personal relationships, imagination, rejuvenation, as well. I concluded the reading of this book with great optimism. One’s brain does not have to wither and die with age. One can and should continue to learn. One may now approach the learning of things that he or she has always wanted to do but was afraid to try, with a totally new point of view, a renewed confidence. Doing so will increase the plasticity of the brain and thus strengthen it overall. When I was young and would sometimes glance ahead, with fear and trepidation, to growing old, I often sought out older people for inspiration. The “seniors” I admired the most were the ones who continued to learn, continued to forge new pathways through life. One woman in particular, Naomi, at age fifty-five—after finishing the rearing of her children and serving as caregiver to both her mother and mother-in-law—finished her BFA and moved to Taos, New Mexico. There she reinvented herself as a visual artist, who counted among her closest friends Agnes Martin, renowned abstract expressionist. Naomi lived well into her eighties, even outlived a daughter who died of cancer, before succumbing to the disease herself. I still think of Naomi as a superb model for all of us. Whenever I’m tempted to feel sorry for myself, I think of Naomi and what she accomplished the last thirty years of her life. We must continue to learn, continue to forge for ourselves the lives that will most bring us satisfaction. By way of the Internet, by way of local schools and classes, we can learn almost anything we wish. It’s the least we can do for ourselves and for those who are to follow us. May they admire us as much as I’ve admired Naomi. Related websites: www.normandoidge.com www.lumosity.com WEDNESDAY: PHOTOGRAPHY A WRITER'S WIT Yellow House Canyon FRIDAY: NEW YORKER FICTION 2014

A WRITER'S WIT Kolorful Kayaks On this day in October 2008, Idaho's Red Fish Lake appeared like glass. Though Ken and I returned to the lake several times in the coming years, we never saw a day that the water was this calm. Moreover, upon one visit, we would see the kayaks piled on top of one another, their vivid colors faded by the elements. This photograph seems to have caught them at their best. Also the sky. The forest. A perfect day, a perfect peace.

FRIDAY: NEW YORKER FICTION 2014 A WRITER'S WIT Route 66 Meets New Destiny  This past weekend Ken and I took yet another chance to flee West Texas. While the Panhandle suffered single-digit temperatures, we experienced, by comparison, much milder temperatures in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The Laguna tribe has built a casino, The Route 66 Casino, on land that would otherwise be useless, and they seem to have turned it into a thriving business. Unlike a number of other casinos we've been to, the Route 66 is kept clean from the busy carpet of old Route 66 icons, and an "asphalt" road making up all the major aisles of the casino and hotel to each and every machine. Employees work hard to keep ashtrays emptied and machines free of finger prints. I find it easy to see how one can get hooked on gambling. The hum of the machines, each with its own two-speakered music coming at you, each with its own characteristic sounds. The thrumming reward you receive when you make fifty dollars on a Wheel of Fortune turn of the wheel. It spurns you to press the Max Bet a few more times. And then you win maybe two hundred dollars, and you think this will go on forever. And sometimes it does, all the way to four hundred dollars. Never mind that you've allowed the machine to suck you dry to the tune of a hundred dollars to win that much. But then there are all the other machines. Penny machines. Dollar machines. Machines with almost every worldly motif: pyramids, TV shows, movies, myths, old and new. There's blackjack, if you're into that sort of thing. Real poker games, though video poker has its own rewards, if you're shrewd enough to outmaneuver the machine. In addition, the place has three eating establishments, a pool, and a work-out area. It's not Vegas, but it's a nice weekend getaway! And it's only six hours from home. FRIDAY: NEW YORKER FICTION 2014

A WRITER'S WIT Fort Ticonderoga, New York, 2003 I'm not sure why I love this photograph so much. Maybe it is the point of view—I was able to scoot down onto a series of steps, aiming my camera at calf level. Perhaps it is the wonderful contrast of dark navy and scarlet. Perhaps it is catching these eighteenth-century gents in a twenty-first century stance, cell phones vibrating in their pockets, their parallel shadows in the afternoon sun of an August day in 2003. Perhaps it is the patch of sky located below the stained drum, the turquoise cannon aged by time. The stone wall still standing after all these years. I could now go back eleven years later, and, though the young men would have spread to the far corners of the earth, this wall would remain essentially the same. I would just bet on it. THURSDAY: NEW YORKER FICTION 2014

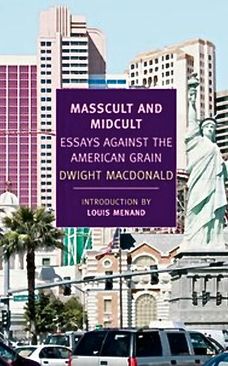

A WRITER'S WIT Terms We Should Remember: Masscult and Midcult  Macdonald, Dwight. John Summers, editor. Louis Menand, introduction. Masscult and Midcult: Essays Against the American Grain. New York Review Books. New York, 2011. I became interested in this book when I saw it reviewed in The New Yorker. Then after I received my copy, I found that this blurb from the back cover gives the reader a great introduction to Macdonald, who published most of these essays prior to 1972: “An uncompromising contrarian, a passionate polemicist, a man of quick wit and wide learning, an anarchist, a pacifist, and a virtuoso of the slashing phrase, Dwight Macdonald was an indefatigable and indomitable critic of America’s susceptibility to well-meaning cultural fakery: all those estimable, eminent, prizewinning works of art that are said to be good and good for you and are not. He dubbed this phenomenon ‘Midcult’ and he attacked it not only an aesthetic but political grounds. Midcult rendered people complacent and compliant, secure in their common stupidity but neither happy nor free.” Wow! Some Nuggets from a Book Filled with Them On the Mags: “This is a magazine-reading country. When one comes back from abroad, the two displays of American abundance that dazzle one are the supermarkets and the newsstands. There are no British equivalents of our Midcult magazines like The Atlantic and the Saturday Review, or of our mass magazines like Life and The Saturday Evening Post and Look, or of our betwixt-&-between magazines like Esquire and The New Yorker (which also encroach on the Little Magazine area). There are, however, several big-circulation women’s magazines, I suppose because the women’s magazine is such an ancient and essential form of journalism that even the English dig it” (59). 1960 On Speculative Thinking: “Books that are speculative rather than informative, that present their authors’ own thinking and sensibility without any apparatus of scientific or journalistic research, sell badly in this country. There is a good market of the latest ‘Inside Russia’ reportage, but when Knopf published Czeslaw Milosz’ The Captive Mind, an original and brilliant analysis of the Communist mentality, it sold less than 3,000 copies. We want to know how what who, when, where, everything but why” (208). 1957 Middlebrow: “The objection to middlebrow, or petty-bourgeois, culture is that it vitiates serious art and thought by reducing it to a democratic-philistine pabulum, dull and tasteless because it is manufactured for a hypothetical ‘common man’ who is assumed (I think wrongly) to be even dumber than the entrepreneurs who condescendingly ‘give the public what it wants.’ Compromise is the essence of midcult, and compromise is fatal to excellence in such matters” (269). 1972 I was fascinated with this man’s informed opinions because essentially little has changed since he made these assertions (when I was but a child or youth). If anything, such conditions have worsened. What can be more Masscult than People Magazine? And has even The New Yorker slipped a bit? Are we getting stupider as a culture, or was Macdonald too smart for his own good?

WEDNESDAY: SHORT ESSAY AND PHOTOGRAPH A WRITER'S WIT Las Vegas: Misc. Signs THURSDAY: FOURTH AND LAST PART OF AN UNFINISHED STORY

A WRITER'S WIT Las Vegas: Architecture THURSDAY: A STORY PART 3

A WRITER'S WIT Las Vegas: Landscape and Pattern THURSDAY: PART 2 OF THE STORY

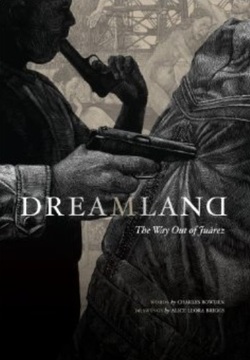

A WRITER'S WIT My Book World  Bowden, Charles and Alice Leora Briggs. Dreamland: the Way Out of Juárez. Austin: University of Texas, 2010. I read this book, illustrated by my friend Alice Briggs, in 2010, when it came out, but for some reason, I did not make a note of it in either my blog or my reading journals. Perhaps it is too disturbing. Perhaps I could not fully grasp what Bowden & Briggs have accomplished. Both Bowden and Briggs spent months, if not years, researching their book, exposing themselves to the same dangers that the residents of Juárez do every day. To get the story of the informant who murders a man while U.S. agents listen in and do nothing, to understand the dynamics of this and a thousand other stories, they both make themselves vulnerable to the ragged life on the border, where, because of a few political decisions made in the past, life is a constant battle between those who are selling drugs and those who would steal the contraband and/or the money it generates. It is a bloody war, one that the United States quietly participates in with its insatiable thirst for more and more illicit drugs. It is a war the U.S. ignores as well, for it is a war so deeply entrenched in the two countries’ economies, whose balance will be tipped if an “Immigration Policy” is ever brought to light. Bowden provides the illuminating prose, and Briggs the exquisite drawings that expand that which he cannot say with words. The gist of Bowden’s entire narrative might be captured in the following passage: “One of the early priests after the conquest of Mexico, Fray Durán, knew the old tongue and listened to the old men and wrote down their tales of what their world had been and what it had meant to them. They had been very rich and feared by other nations. They told the priest of the tribute once brought to their emperor: mantles of various designs and colors, gold, feathers, jewelry, cacao, every eighty days a million Indians trudged in bearing tribute and the list was so complete that even lice and fleas were brought and offered. The tribute collectors told the emperor, ‘O powerful lord, let not our arrival disturb your powerful heart and peaceful spirit, nor shall we be the cause of some sudden alarm that might provoke an illness for you. You well know that we are you vassals and in your presence we are nothing but rubbish and dirt.’ ¶ That was half a millennium ago and yet the rich still get tribute and the people who give them tribute feel as dirt and rubbish. ¶ For years and decades, for almost a century, people have looked at this system and sensed change or noticed hopes of change. And yet they all wait for change” (67). Bowden is well aware that this journey the Mexican people make is one that started long ago and continues, for all we know, far into the future: The combination of Bowden’s stunning and lyrical prose combined with Briggs’s dramatic but subtle sgraffito illustrations make a powerful statement of our problems on the border. No wonder some want to fortify the barriers that already exist there. It is an ugly world, and we certainly don’t want it spilling over into ours. “In the Florentine Codex, a record of the Indians’ ways that Cortés crushed with his new empire, it is noted that men who die in war go to the house of the sun and then they become birds or butterflies and dance from flower to flower sucking honey. In the old tongue, flower is xochitl, death is miquiztli” (80).  Sáenz, Benjamin Alire. Everything Begins and Ends at the Kentucky Club. El Paso: Cinco Puntos, 2012. The Kentucky Club is a bar on Avenida Juárez in Juárez, the twin city to El Paso, Texas. Most of these seven stories reference a number of things in each one: The Kentucky Club itself, bourbon (or some other strong liquor), stout coffee, fathers who fail their sons in a variety of big ways, and mostly men who fail each other in love. Sáenz’s style is deceptively simple, strong on declarative sentences and plenty of pages with a lot of white space because his dialog is, if not terse, then spare, lean. Most of the characters, gay men of various ages, live in Sunset Heights, a neighborhood in El Paso, but plenty of them cross the bridge between the two cities, the two countries as easily as most of them switch from Spanish to English—as if they are two forms of the same language. That’s life on the border: with its own lingo, its own culture, like many of the men in these stories, crossing easily from one life to another, but not without a price. And one must not construe that this is a "narrow" book of gay men’s fiction, many of which made their way onto the shelves in the late eighties because gay men were hungry to read about themselves. It is not one of those books. Some of the protagonists are straight, some gay, some are bisexual. Each one is his own person, whether he is yet whole or not. In the final story, “The Hunting Game,” the main character, a high school counselor, speaks of one of his students, who has been abused all his life by his father. Sáenz’s metaphors, like his prose, are deceptively simple: “We grabbed a bite to eat. He ate as if he’d never tasted a burger before. God, that boy had a hunger in him. It almost hurt to watch. ‘I’ll be eighteen in three months. And I’m going away. And he’ll never be able to find me’” (209). The image is so simple, yet so profound, the hamburger that symbolizes a future that might just satisfy the boy’s hunger to be loved. It has little to do with food; it has to do with hunger, the hunger of the human spirit to find meaning. On the same page, Sáenz demonstrates through “dream” how the paths of these two males (one older, one very young) will cross one another by virtue of the pain both have suffered at the hands of their fathers: “I wanted to tell him that his father would always own a piece of him, that he would have dreams of his father chasing him, dreams of a father catching him and shoving him in a car and driving him back home, dreams where he could see every angry wrinkle on his father’s face as he held up the belt like a whip. He would find out on his own. He would have to learn how to save himself from everything he’d been through. Salvation existed in his own broken heart and he’d have to find a way to get at it. It all sucked, it sucked like hell. I didn’t know what to tell him so I lied to him again. ‘He’ll just be a bad memory one day.’ He nodded I don’t think he really believed me, but he wasn’t about to call me a liar” (209). This PEN/Faulkner award winner has written seven striking stories I believe I should read again and again because I sense there is much I may have missed the first time around. This book is one that my friend Alice Leora Briggs gave me. For me, it is a bookend to the one she illustrated, Dreamland, profiled above. This one gives the reader yet another view of life along the border between Mexico and Texas.

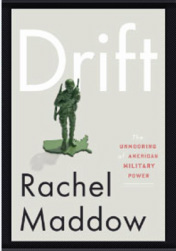

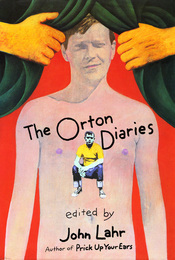

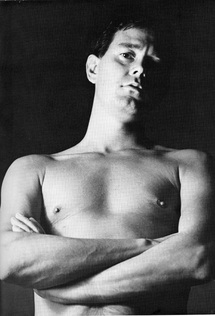

Men in power can easily change borders on maps with the quick exchange of currency, but borders that exist in people’s hearts are much more difficult to traverse. WEDNESDAY: LAS VEGAS PHOTO ESSAY Ken Dixon at the Museum of South Texas  Dixon's Order & Disorder: "Maze" Dixon's Order & Disorder: "Maze" For several decades Ken Dixon, visual artist, has provided exhibitions for the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi, Texas. On Saturday, November 9, the museum honored all the artists who have contributed work to its permanent collection, an exhibition entitled "Forty Works for Forty Years." For more details click on the museum link. Look below to view a slideshow of snapshots from the evening (all iPhone pics). Nighthawks Reading  Sporting My "Burroughs" Look Sporting My "Burroughs" Look For over five years I've been part of a writing group that meets at the local Unitarian church. For a modest annual fee, we meet monthly to critique and celebrate each others' writing. Our approach is positive, even when the piece under consideration may have some difficulties. As a result of this nurturing approach, we've all grown, and so has our confidence. New works are constantly finding their way into print because of our sensitive efforts to help one another grow. On Thursday, November 14, we staged a reading of our recent works-in-progress. Barbara Brannon read a series of sonnets that trace the life of her adult daughter. Michelle Kraft shared a prose piece about how her childhood home in North Texas later became home to an Army Corps of Engineers lake. Marilyn Westfall, poet and leader of our group, read a number of linked poems, among others, about a recent trip to the Isle of Wight off the coast of England. Actor and playwright Juanice Myers organized a troupe of players to present her monologues limning characters—from an old woman regretting how her looks have faded to one that looks back at the fun times the alcoholics in her family provided. I read excerpts from the first chapter of my memoir concerning my twenty-seven years of public school teaching. Thanks to everyone who came, and to the Unitarian leadership for providing us with a place to present our work to the public. Below find photos documenting our efforts. Ken Dixon, photographer.  Dixon Minutes Before Exhibition Opens Dixon Minutes Before Exhibition Opens My partner Ken Dixon recently produced an exhibition, which opened at William Campbell Contemporary Art Gallery in Fort Worth, Texas on October 19 and will remain through November 16. Titled 3 Short Stories & 12 Options, the collection is comprised of "fifteen large-scale, mixed media pieces completed over the past year and inspired by Dixon's decades-long fascination with the Texas Hill Country and northeastern United States. A visual convergence of art, science, and culture, the collection explores themes of order and disorder on both macro and micro levels within the environment. Additionally, Dixon addresses the role of technology in art and nature as he intermingles digital imaging with painting and collage." Needless to say, I couldn't be happier for his continued success. Please click on the link to Campbell's gallery to find out more. I've also placed a link to the gallery in my sidebar, should one need to locate it later rather than sooner. If you will be in the DFW area in the next few weeks, stop in and take a look! Below are photos from the opening festivities. All My Antique Valentines  I've said this before, but my mother saved everything. In this case she collected scores of Valentine cards from the 1920s and 1930s. I posted them on a bulletin board when I taught sixth grade in the seventies and eighties. Even then they were antiques, but the kids seemed to enjoy them. I don't know about Valentine cards today, but these rely heavily on the pun. A number of them have moving parts. Most of them have a good sense of design and plenty of RED. I share them once again with all you grown-up kids out there! Trash Galore In many of my posts I've spoken of items that do not recycle. An artist friend, Aidan Grey, of Denver, told me he would take any of those items when I was through writing about them. So I later packaged them up and sent them off. Recently, his show, Trash, opened at Denver's Edge Gallery. To your left you see my photo of the blue rubber rings that Target Pharmacy uses to identify its prescription bottles. Note below how Aidan transforms this gasket trash, as well as other pieces, into art. My Book World Drift by Rachel Maddow I made a number of notes (as well as using Kindle’s handy yellow highlighter), but I fear they would interest only me, so I introduce Rachel Maddow's book by way of the following passage. “‘Not since the peace-time years between World War I and World War II,’ according to a 2011 Pew Research Center study, ‘has a smaller share of Americans served in the armed forces.’ Half of the American public says it has not been even marginally affected by ten years of constant war” (202). And yet I wonder . . . haven’t more than half of Americans been . . . affected? Haven’t more than half of us known at least one family affected by the war, at least known of a soldier (even a friend of a friend) killed or disabled by the war? Haven’t more than half of us known at least one person whose business has folded during this decade in which the war-induced deficit (along with other controllable factors) has crushed the economy? In addition to demonstrating how the country has drifted to a new kind of warfare—distant, affecting civilian life hardly at all, almost unreal because it’s kept out of the public eye—Maddow brings to our attention how little U.S. citizens have at stake, apparently. Because our last two wars have been fought without a draft, without civilian sacrifice (except for, needless to say, the friends and relatives of over 4,500 men and women), without the approval of the civilian population who is paying and will continue to pay for these wars—we are a population that has drifted into war and will be less and less likely to drift out of it. My grandfather, my father, my uncles, my cousin all fought in various wars with mixed results. What will be the ultimate result of our decade of war? Maddow, despite the progressive stance she takes on her show, manages to approach her subject objectively--siting support from military experts at both ends of the political spectrum. My only criticism concerns Maddow’s prose. Her writing is both elegant and pedestrian, at turns. It is elegant when she is making a point, employing “drift” as a fine extended metaphor throughout the book, articulating herself with a vocabulary that reflects her education. On the other hand, her prose sometimes reads as if she has dictated one of her evening presentations complete with single-word fragments, not to mention using the word “busted.” Okay, it’s fine to opt for busted in informal usage or a context pertaining to police work (The detective busted him on the spot.), but in a book in which Maddow has gone to great lengths to be accurate and eloquent, might she please avoid the word “busted?” A “busted fuel line” (230) could easily be transformed to a “broken fuel line,” a “damaged fuel line.” In another instance, “broke-down busted, overgrown, spongy stairs,” (243) seems a bit like overkill—particularly in the context of describing the home Maddow and her partner are buying. Surely any editor over the age of forty—an editor who has mastered grammar and composition—could catch these instances and elide them. 25th Anniversary of Prick Up Your eArs In 1987 two books concerning the life of British playwright Joe Orton were published. In June of that year I read The Orton Diaries edited by New Yorker critic John Lahr (son of Wizard of Oz actor Burt Lahr). Orton’s journal is comprised of brutally frank entries about his openly gay life in 1960s London. He offers his opinions on literature and the world of the theatre that he so desperately seeks to be a part of. Below is a sample of his candor.  Joe Orton, Playwright Joe Orton, Playwright “When I left, I took the Piccadilly line to Holloway Road and popped into a little pissoir [rest room at the Tube Station]—just four pissers. It was dark because somebody had taken the bulb away. There were three figures pissing. I had a piss and, as my eyes became used to the gloom I saw that only one of the figures was worth having—a labouring type, big, with cropped hair and, as far as I could see, wearing jeans and a dark short coat. Another man entered and the man next to the labourer moved away, not out of the place altogether, but back against the wall. The new man had a pee and left the place and, before the man against the wall could return to his place, I nipped in there sharpish and stood next to the labourer. I put my hand down and felt his cock, he immediately started to play with mine. The youngish man with fair hair, standing back against the wall, went into the vacant place. I unbuttoned the top of my jeans and unloosened my belt in order to allow the labourer free reign with my balls. The man next to me began to feel my bum. At this point a fifth man entered. Nobody moved. It was dark. Just a little light spilled into the place from the street, not enough to see immediately. The man next to me moved back to allow the fifth man to piss. But the fifth man very quickly flashed his cock and the man next to me returned to my side lifting up my coat and shoving his hand down the back of my trousers. The fifth man kept puffing on a cigarette and, by the glowing end, watching. A sixth man came into the pissoir” (105).  Orton Orton On and on Orton continues describing a situation where as many as eight men engage in illicit, illegal sex. As far as I know, he never used this material per se in any of his dramatic or fictional works, but here he arranges the material as if he is creating a scene in a novel—and it is quite instructional. Orton is brutally frank concerning more substantive matters, as well. “I got to Brian Epstein’s office at 4:45. I looked through The New Yorker. How dead and professional it all is. Calculated. Not an unexpected line. Unfunny and dead. The epitaph of America” (73). Whether he’s right or wrong, he seems to state his opinion with authority.  In 1987 John Lahr published a biography of Orton called Prick Up Your Ears (a motion picture starring Gary Oldman as Orton and Alfred Molina as Halliwell was soon followed). Lahr borrows his title, Prick Up Your Ears, from one of Orton’s that he himself deemed “too good to waste on a film [Up Against It]” (88). “Ears” is Orton's anagram for his favorite part of the male anatomy. From a large number of sources, Lahr details Orton’s life from early childhood, to his first few successes on the London stage, to his relationship with lover, Kenneth Halliwell, who, in 1967 bludgeoned thirty-four year-old Orton to death with a hammer and then killed himself. Fifteen years earlier, Halliwell, well-educated but lonely, had taken a poor teen-aged Orton under his wing, to educate him and provide him a safe haven in which he might develop his craft. Halliwell considered himself the writer in their duo, and when Orton began to experience success that included a bigger bank account, Halliwell’s jealousy got the best of him. One can extrapolate from Orton’s journal entries that he was fed up with Halliwell and nearly ready to leave him. Recently, I re-read both of the Orton books, twenty-five years after first devouring them. I've also seen the film version of his hit play, Entertaining Mr. Sloane. I still find his works astonishing. In them I find the courage to be the writer I would like to be: saying that which I believe is true, rather than that which will be acceptable to the public. Of course, I still succumb the latter. I would like to be read by a broad audience. Still . . . I look to his journals for the right tone, the point of view that tells the rest of the world to go f@#k themselves while creating the works I wish to create. A Workshop For Editing the NovelIn July I attended a workshop in Alpine, Texas sponsored by the Writers League of Texas. Alpine is part of an interesting trio of towns in far West Texas, Marfa and Ft. Davis being the other two. Alpine is home of Sul Ross State University. More like a small college nestled into a shining hill, it served as a great setting for our workshop. As we only had an hour to eat lunch each day, we often ate a great meal in the union. Several deluges pelted us during the week, but no one complained. Just a year before the area had suffered great loss from fires due to the long drought (see rainbow photo by Tanner Quigg.) Author Carol Dawson, with at least four books to her credit, conducted the week-long course on how to revise and edit a novel. I’ve attended writing workshops before, mostly those concerning the writing of short stories. In this one, every exercise had to do with the novel manuscript I had brought to the group. At our first meeting, Ms. Dawson told an amusing tale of overhearing one of her students saying, “If you take Carol’s class, you’d better wear your big-girl panties.” Even though our group was evenly divided between men and women, no one disagreed with the idea that we were in for a tough ride. Actually, the workshop—painful as it was at times (seems that my novel didn’t have a hook, that opening line that makes someone want to forget his or her chores and read on into the night)—was also quite helpful. Editing requires one to leave his or her creative shoes at the door. It requires one to look at his or her text as if it belongs to someone else. One must cut, cut, cut. One must chop "ly" adverbs away from speech attributions (he said hesitantly). One must cut most adjectives. One must cut material that doesn’t move the narrative along. I returned home with much to think about, and much to do. I highly recommend Dawson’s course, particularly if it’s held in Alpine.  Poet Scott Wiggerman Poet Scott Wiggerman On Thursday night, two of the WLT’s instructors gave readings at Front Street Books in Alpine. Poet Scott Wiggerman read from his recent volume of poetry entitled Presence. In addition to his writing pursuits, he is chief editor of http://dosgatospress.org/ in Austin.  I loved hearing Scott read his poem, “Letter to My Father-in-Law,” in which the persona skewers his partner's father for not accepting him. It begins with “I rode your son real hard last night/broke him like a wild stallion/head puled back, nostrils wide as moons . . . .” The piece--the tone of which is bold, angry--ends with the lines, “I’m reconciled to the fact that you’ll be dead/before I ever set foot on your farm/I should like to see the house your son grew up in/the acres he worked, the home he escaped/But the biggest draw will be standing on the land/that I’d been banned from, knowing that you/will be in your grave, writhing without a shotgun/ when your son and I get down in your dirt.” Whooee, what a ride.  Joe Nick Patoski Joe Nick Patoski Joe Nick Patoski, read passages from two of his books: Dallas Cowboys: The Outrageous History of the Biggest, Loudest, Most Hated, Best Loved Football Team in America and his 2008 biography of Willie Nelson. Dallas Cowboys is more of an expose of the city of Dallas than it is about the cowboys. His prose is as wild as the rides he takes you on. Patient BacklashI've received a couple of great comments about my last post, “Tickety Tick Tick Tick,” and I’d like to share them with you. My friend Val Komkov-Hill has this to say: “Can’t tell you how much I related to your doctor story. Mine is not as dire but at Christmas my PCP, let’s call her Dr. No Nonsense, said my lab tests had found hematuria (red blood cells in my urine) and set me up to see a urologist, who, of course I could not get in to see until two weeks ago. (four months later) Good thing I wasn’t, you know, dying. I had shifted my Yoga classes since I had to show up when they deigned or it would be another 3 month wait while I stewed about whether or not I had bladder cancer. The DAY before the appt. they called and said there was a problem because my Blue Cross insurance listed a different PCP, one I hadn’t seen in 20 years. I said no it did not and got my BXBS card out to read the correct PCP printed on it. They said I needed more proof, could my doctor refax insurance info, or they would have to reschedule. Heaven forbid they didn’t get their pound of flesh. Again, like you, calls to my PCP’s clinic that never got answered by a real person, and me finally driving over in a huff, much like you, to talk to a REAL person. Long story short, got problem solved, Bladdercam (ouch) showed pristine bladder. Kidneys singing happily. All well. Except, I got a call from the urologist two days ago. My sample I left for more testing was somehow leaked (translation: some fool dropped it or lost it) could I come back and pee again. Fine, let me drink a gallon of water and I’ll be on my way.” Hm. Val’s comment has that same buzz of rage beneath the surface that I felt while writing my post. When I ask Val if I can quote her, she says, “Ha, I don’t mind if you use my name. I used to be so terribly shy and modest but after awhile, having been probed and x-rayed, and palpated, and poked, I kind of got over it.” A person who wishes to remain anonymous shares the following: “Your story of dealing with doctor, nurse/receptionist, pharmacy, reminds me of experiences Jean Craig spoke of in her book Between Hello and Goodbye. It’s all so very frustrating." Yes, yes, it is. Crystal BridgesOn May 9th three of us drive to Crystal Bridges of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas—it’s about an hour from Eureka Springs, where we are staying with friend and former Lubbock resident, Alice. This area of northwest Arkansas is now like a typical sprawling suburbia—replete with all the generic retail outlets one expects to see in such a setting—except that this megalopolis is not a satellite of any city. The nearly 500,000 people of northwest Arkansas live in a handful of burbs stretching from Bentonville in the north to south of Fayetteville, where the University of Arkansas is located—and all are serviced by I-540, which connects with I-40. Keep this backdrop in mind as you picture Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges (not to be confused with our friend Alice). As we go through the unassuming entrance, we drive along a wooded area on a smooth new asphalt road. The shoulders are abundant with what look like spring daisies—whites and yellows clumped together so tightly that there exists little space between them. We see that the outdoor parking is full so we investigate the indoor lot on the Lower Level. There is one disabled parking spot left, and so we take it. Alice uses the electrified system in the back of her van to lower her electrified wheelchair to the ground. Ken and I trot to keep up with Alice who zooms ahead. Inside Ken “checks in” (one only has to pay $5 for the special showing of The Hudson River School Exhibit). Otherwise, entry to Crystal Bridges is virtually free to anyone. It is our plan to eat lunch in the museum’s restaurant, Eleven. Unlike some museums it is designed to handle large groups. Even though Eleven is apparently full, we have no problem securing a table for three. The cuisine and service are great, and we leave fortified to begin our trek through the museum. I first became aware of Crystal Bridges on CBS Sunday Morning—a piece that emphasized the visual and architectural aesthetics of the museum itself. On our visit the museum is teeming with people—families, school children, and seniors, people with all kinds of accents—not just the locals. Alice says that when she visited in the winter, the place was empty. It is now overloaded with friendly and polite docents, because the rules must be enforced: no flash photography (none at all for The Hudson River School Exhibit); no drinks or food, no gum, no pens; no pointing at a painting. And you can get no closer than eighteen inches to a work. If you must read the identifying information, lean in directly in front of the sign, not the painting. Crystal Bridges is constructed of a series of halls or pods that lead easily from one to the next. Each is large in length, width, and height. Very few paintings take full advantage of the latter—which portends well for artists of the future—whose works may indeed aspire to great heights. The halls move through more than two hundred years of American art (Colonial, 19th Century, Modern) until finally you end up in the Contemporary Gallery, which includes Abstract Expressionism—a breath of fresh air, if you will, after traveling through the past. Here you see square inside square, squiggles, solid colors, all of them providing a visual relief from two centuries of more figurative works. This pleasant progression seems a tribute to the museum staff’s layout of the paintings. After four and a half hours I decide to go outside. Even though it is 68 degrees in the sun, the air is cooler than inside what could well be the most modern museum in the country. I photograph the patio/amphitheater area and take exterior shots all of the halls or pods. Crystal Bridges is landscaped beautifully and contains a substantive sculpture garden. Unfortunately, this visit we do not have time to investigate it. Ms. Alice Walton, daughter of Sam Walton, has been reviled by some for having the audacity to snatch up what are considered to be very important paintings that some feel should never have left their former homes (yet usually paying handsomely for each piece), but after seeing what Ms. Walton has created here, one certainly cannot fault her with not having a great sense of philanthropy. We can complain all we want about Wal-Mart’s faults, foibles, and failings, but Ms. Walton has amassed a world-class collection of art and installed it in a world-class facility—one that virtually anyone in the world can walk in and see . . . enjoy . . . appreciate . . . savor. If she has provided the proper endowment—and one must assume she has—this initial collection is something that can only grow and last well into the future. And maybe, just maybe, Wal-Mart will mend its ways (or is that a political matter of applying more pressure?). We can always hope. Our day ends with a quick trip south on I-540 for an early dinner at P.F. Chang’s located in a shopping area that in Alice’s opinion outclasses the mall in Fayetteville. On the way back to Eureka Springs, just past dusk, we cross over the (yikes) one-lane Beaver Bridge that we used earlier in the day when the sky was bright, and it makes me feel as if I’ve passed from one world to another—back from the flat, sprawling megalopolis of Northwest Arkansas to the bucolic life of rocks and rills that seem as timeless as art itself. See more pictures of our trip by going to Photos, "2010 To Present." Artfully Repurposing Our Trash Collectibles Repurposing Keys Project Repurposing Keys Project If any of you have received the May/June issue of Sierra, you know of the column "Repurpose | Trash Into Treasure." This time the page demonstrates to the reader how to take old keys (and we all have a million of 'em, particularly since so many aspects of our lives have gone keyless). You can go to the Sierra Club Web site to locate step-by-step directions. Sierra Club based their project on one by Nicholas Torretta at viraroque.blogspot.com. Let me know of your own such projects. I myself have begun to re-purpose non-recyclable items if I can. Remember the blue rubber rings that come around the necks of my pharmaceutical bottles? The plastic bread bag clips? Lids, lids, and more lids? I packaged up all those items featured in my "Item's That Won't Recycle" posts (see Archives) and sent them to artist friend Aidan Grey in Denver CO. Click on his name to read a review of his recent exhibition at Denver's Edge Gallery. In an e-mail, Aidan told me,"My next show is going to be 'trashGod,' making icons of the gods of trash and waste, to open at the end of July." I believe the show will probably be at the Edge. Check out their "Schedule" page, and I'll keep you posted in case you live in the Denver area or will be visiting during the time the show is open. I can't wait to see how Aidan re-purposes America's trash. My Book World Donald W. Richards, my mother’s first cousin, has published a novel entitled Call Me Elmer. Set in the late 1930s, this novel begins when a family traveling to a new life in the West accidentally leaves their eighteen year-old son behind during a rest break. He does wander away from the car, so, in a way it’s his own fault—but the reader has to wonder why a family would leave a member behind and not return to the scene. The young man, Mathew Russell, has no choice but to keep on walking and finds a job working for Middleton Farms somewhere, I’m guessing, in the Southwest (Richards never tells the exact location that Mathew comes from, nor the one where he winds up, giving the narrative an "Everyman" feel to it). Mathew makes quite an impression on the owners of the farm, not to mention their granddaughter, Kathy, and works his way up in the organization. He is not afraid to speak his mind and actually helps the Middleton Farm make some significant changes. Mr. Middleton, because he had lost a son named Elmer (Kathy’s father), re-names Mathew, and Mathew eventually adopts Elmer as his middle name. Taking the name is significant because “Mathew” seems to represent his old life and “Elmer” his new life with the Middletons. Accepting both near the novel’s end brings an integration to his life he doesn’t have at the beginning. World War II interrupts Mathew Elmer’s relationship with Kathy and the Middletons, not to mention his university life and career aspirations. He plays a significant part in the war effort, recruited precisely because of his agricultural expertise. While in England Mathew encounters a man whom he identifies as his brother. The man, however, denies any knowledge of having ever known Mathew. This event could confuse the reader; it's sort of an emotional slap in the face. Is the brother angry that Mathew never tries to find his family? Is Mathew afraid to confront his brother with the question as to why the family never returns for him? At war’s end Mathew returns to Middleton Farms, and he and Kathy practically marry on the spot in 1945. Overall, the novel is quite enjoyable, and Richards’s elegant prose contributes to a fine reading experience. It’s a pleasure to read someone who has a strong command of the English language and can communicate his thoughts clearly. I wish Don well with Call Me Elmer as well as his next book, which he’s told me he’s close to completing. Call Me Elmer is published by Ghost River Images, and you can probably purchase a copy by contacting the author at <[email protected]>. |

AUTHOR

Richard Jespers is a writer living in Lubbock, Texas, USA. See my profile at Author Central:

http://amazon.com/author/rjespers Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

Blogroll

Websites

|