A WRITER'S WIT

I think we Southerners have talked a fair amount of malarkey about the mystique of being Southern.

Reynolds Price

Born February 1, 1933

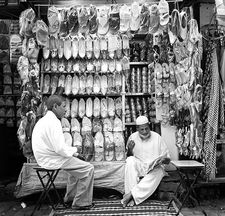

DK's Grog

2 oz. of Jack Daniels

1 or 2 oz. of Amaretto (or some other tasty liqueur)

3 oz. of Half and Half (some recipes indicate whole milk, ye gods)

1-2 tsp. of powdered sugar (to taste; I happen to have TWO sweet tooths . . . teeth)

Nutmeg

Caloric Intake: at least 5,000

This is one of those concoctions that MUST be shaken with ice until homogeneous, never stirred or mixed. Save the nutmeg until you have poured the drink into a tumbler and sprinkle a tiny bit across the top. The pleasing arrangement, rather like tea leaves, will forecast which team is going to win the Super Bowl. If you do it right you won't care. Otherwise, the dots of nutmeg may spell out your future, if you’ll win that case in court, whether the boss you hate will choke on his or her sandwich and die all alone in his or her chair. It’s powerful stuff, so be careful with the knowledge you attain.

The world has a long history of gathering in an arena to watch men smash each other up. It's the reason why high schools still teach Beowulf. Even today we must have dragons to slay, and as we look on, we must have grog . . . gobs of mighty grog!

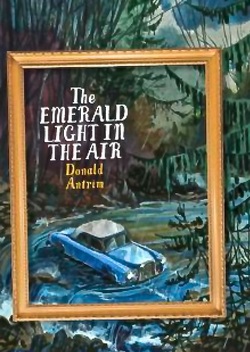

TUESDAY: MY BOOK WORLD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed