Red Leaves Rare This Season

Red Leaves Rare This Season My Book World

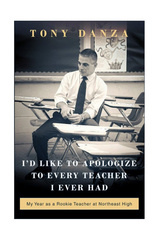

I didn’t want to like this book. What could a TV actor learn from one short year in the classroom, when I’d spent nearly thirty there? What could he share with me that I didn’t already know? I first became aware of his book when Danza, actor and star of Taxi, appeared for a reading on C-SPAN’s Book-TV. He seemed a little cocky even as he spoke of how difficult the job of teaching English to tenth graders had been—and then as he continued, I learned that much of his motivation for undertaking the year was to make a reality show for the A&E Network! Danza didn’t even read from his pages but spoke extemporaneously of his nine-month stint. The producers later pulled the plug, and Danza taught the second semester without cameras in the room, a relief, he said. Maybe that was the trick, his willingness to remain in the classroom, that made me go on.

I was pleasantly surprised with Mr. Danza’s saga. He may have worked harder (at sixty) than I had my first year of teaching when I was but twenty-six. With a certain position of power and privilege, Danza seized the opportunity to let the public know—what the rest of us who did it for a career can’t necessarily do—how stupendously difficult it is to be a good teacher.

I want to list some nuggets of truth and/or wisdom he shares with the reader.

This one comes from a retired teacher at Tony’s school, Philadelphia’s Northeast High: “Seating chart. Make one up, use pencil. Do not rearrange chairs unless you are able to put them back neatly before the bell rings every day” (35). How right this sage is. I made up a new seating chart every six weeks period, breaking up cliques that had been formed in the junior highs feeding our school. The practice allowed me to learn pupils’ names, all 144 of them, rather quickly. And you must always put the chairs back in the rows where you had them. Why? So that the next group can perceive that you’re just as ready for them as you were the last class.

After Danza demonstrates his seriousness, Northeast teachers begin to open up. “Others are kinder. They offer advice and tell me what they believe it takes to be a good teacher. ‘You have to be prepared to play many roles,’ says an older woman who’s been teaching for decades. ‘You have to be a mother, father, sister, brother, social worker, counselor, friend, and anything else they need.’ They tell me some heart-wrenching stories about kids who’ve come to school hungry, or late because gunfire outside their bedroom kept them up all night, or who don’t talk in class because of abuse inside their bedroom. They tell me about teachers almost adopting their students to keep them from falling into the abyss of foster care or homelessness. ‘Adoption fantasy,’ one man says, ‘comes with the territory’” (48). I never knew that’s what that was called: all the years in which I could have adopted any number of kids if so allowed and if I’d had the resources to do so—the one(s) who captured my heart for no good reason at all except that I sensed a need.

“It’s beginning to dawn on me just how much work teachers are besieged with outside the classroom. This, I think, is another thing that politicians and the media rarely mention” (49). Aha. Forty hours working in the building. Another twenty at home grading essays until your eyes bleed.

“Another paradox of education in America. They want the experienced teachers to retire and make room for new teachers they can pay less. Talk about your penny-wise” (73). I’ll expand the paradox. Just when teachers are gaining all the wisdom, all the knowledge a lifetime can give them, when they could do the most good, like doctors or lawyers who’ve reached their stride—they finally have not the energy to continue. All the cogs and wheels of the public school machinery (it’s never really the students that tire you) finally wear this fine individual to a pulp, and when they offer you the bronze parachute of a pension, you take it. (Gold, are you kidding? That’s only for administrators and state legislators.)

I could go on and on, but suffice it to say that Mr. Danza really gives his all to the job at Northeast High. He weeps at the drop of a hat (both in and out of class)—something any teacher will tell you is true on those days when you feel like an absolute failure (or a depressive, which may be worse). He tries new methods when others don’t work. He learns from his mistakes (and he makes, like most of us, a lot of them). He organizes field trips for his Philly kids to see a show on Broadway in New York. He organizes a teacher talent show that really energizes the faculty. He’s one of those sparks that every teaching staff needs, and then suddenly the year is ended. He is both devastated and relieved. Yes, when you reach that point in the year, you are both. You can’t wait to stop hitting your finger with a hammer. At the same time, you’ve spent 183 days watching your pupils grow and change, something you’ve had a small part in, and a certain side of you doesn’t want it to be over.

Mr. Danza is asked over and over again by students and fellow teachers if he’s going to come back next year. And each time he says, “I don’t know.” What a luxury. I don’t know. At the same time, I can’t be too critical. There were many years that if someone had dumped a sack of money at my doorstep, I would have walked away. Never to return.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed