A WRITER'S WIT

The kind of people who always go on about whether a thing is in good taste invariably have very bad taste.

Joe Orton, Playwright

Born January 1, 1933

Honjo

Honjo “Then my eyes fastened on two protruding screws, one on each side of the interior of Hana’s letter box: in their functional ugliness they were reassuring” (65). “People seemed to take me more seriously—as if I’d been initiated into something after all, although nothing had happened” (65).

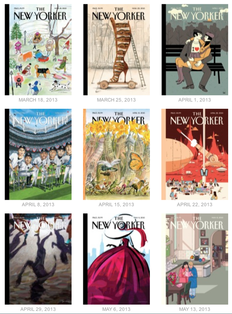

Victo Ngai

Victo Ngai Victo Ngai, Illustrator

José Manuel Navia

José Manuel Navia José Manuel Navia, Photographer

Jashar Awan

Jashar Awan Jashar Awan, Illustrator

Honjo

Honjo Honjo, Photographer

Eric Hanson

Eric Hanson Eric Hanson, Illustrator

Goodman/Cornett

Goodman/Cornett Timothy Goodman, Lettering

Grant Cornett, Photographer

Goodman/Cornett

Goodman/Cornett Timothy Goodman, Lettering

Grant Cornett, Photographer

Goodman, Cornett, Granger

Goodman, Cornett, Granger “It was all he could do to help her, the only alternative he could provide. And the only way to take her away was to marry her. To take his brother’s place, to raise his child, to come to love her as Udayan had. To follow him in a way that felt perverse, that felt ordained. That felt at once right and wrong” (88). In the end Gauri says, “[Udayan] once told me, because he got married before you, that he wanted you to be the first to have a child” (89).

Timothy Goodman, Lettering

Grant Cornett, Photographer

Granger Collection, Archive

Michele Borzoni

Michele Borzoni Michele Borzoni, Photographer

Scott Musgrove

Scott Musgrove “Then he saw his old name on the lid and his mood darkened. Was he so different from that easily injured boy? Sometimes it seemed that the only point to life was death. Dirt slid from the shovel back into the hole. Robert hoped it sounded like peaceful rain, because after that the rest was a storm” (65).

Scott Musgrove, Illustrator

Larry Towell

Larry Towell “Espejo rented out their cell, and in the evening, as they lay on their bunks, they could still feel the warmth of those phantom bodies. Their perfumed scent. It was the only time the stench of the prison dissipated, though, in some ways this other smell was worse. It reminded them of everything they were missing” (61).

Larry Towell, Photographer

Moises Saman

Moises Saman Moises Saman, Photographer

Jeffrey Decoster

Jeffrey Decoster Jeffrey Decoster, Photographer

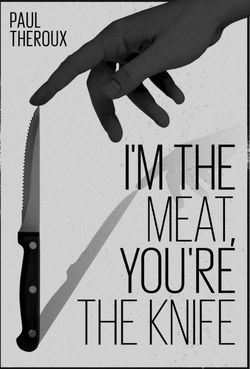

“I had begun to cry, sniffling, then sobbing with an odd hopeless honk of despair.

‘He thought the world of you,’ she said. ‘Dad knew that. He used to talk about it to me.’ And then she was comforting me. ‘Go on, let it out, Jay. I know how much he meant to you’” (73).

Theroux’s latest book is The Lower River.

[The magazine gives no credit for the illustration.]

Leslie Herman

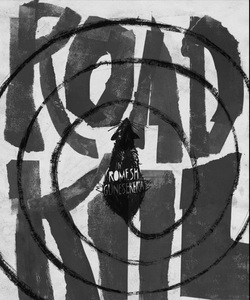

Leslie Herman “Blackness is like ink seeping through my eyes and into my head.”

“It is only when you come to a stop like this, in a black night in the middle of nowhere, that things wobble a bit and you wonder about the purpose of roads. You sit in the dark, frightened at the life you’ve led and the things you’ve left undone. You can only hope that in the long run it won’t matter, but that in itself is no consolation.”

Leslie Herman, Illustrator

Javier Jaén

Javier Jaén Javier Jaén, Illustrator

READ "The Big Middle" ON THURSDAY

RSS Feed

RSS Feed