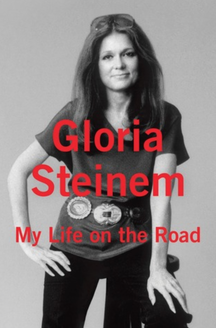

A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

In 1972, when I’m a graduate student at Southern Methodist University, I attend an event in which Gloria Steinem speaks to the student body. Her address, along with an inter-term class entitled Women in the Church and Society, converts me almost overnight from a chauvinistic twenty-three-year-old seminarian, who can’t lift a finger to help out his working wife, to a young man who begins to mend his ways. The month-long class precipitates a metamorphosis that ends in my coming out as a gay man and deciding the Church will not be a very felicitous place for me to work for the rest of my life. Feminism saves my life. The same philosophy that frees millions of women from sex roles also frees men from those roles passed on to them by their fathers, whether they want to be like their fathers or not.

Steinem begins with a dedication that is more like a confession. She thanks, posthumously, the British doctor, who performs an abortion for her twenty-two-year-old personage. She promises not to tell anyone about the procedure but also promises to do what she wants with her life. She says, “I’ve done the best I could with my life. This book is for you.”

Almost immediately, Steinem leaves England for India, where she spends two years helping women to organize. But first she takes the reader back to her childhood in Toledo, Ohio. Because she attends Smith College, I always assume she’s had a rather privileged childhood. Not so. Her father is an itinerant antique dealer, who packs up his family in a car every summer to search for treasures and adventures. Her mother, however, suffers from depression, more than likely for having never achieved the things that she would have liked, asserts the author.

Steinem’s travels include work as a journalist in the 1960s; her most famous article may be one in which she is hired as a Playboy Bunny and writes a scathing exposé of the Bunnies’ working conditions. She establishes Ms. magazine. She helps to put together the 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston and extends her travels to help Native women organize on their reservations—places where largely non-tribal men rape females with impunity. She develops lifelong relationships from coast to coast and around the world. This tome treats women’s issues with wisdom, humor, and a devotion that is unmatched. Like her five previous books, this one should be read by men and women alike. Steinem is a national treasure because of her courage and devotion to improving the lives of women everywhere, and we should never forget it.

Some golden nuggets from Ms. Steinem’s book:

“I could see that, because the Gandhians listened, they were listened to. Because they depended on generosity, they created generosity. Because they walked a nonviolent path, they made one seem possible. This was the practical organizing wisdom they taught me:

If you want people to listen to you, you have to listen to them.

If you hope people will change how they live, you have to know how they live.

If you want people to see you, you have to sit down with them eye-to-eye” (37).

“We might have known sooner that the most reliable predictor of whether a country is violent within itself—or will use military violence against another country—is not poverty, natural resources, religion, or even degree of democracy; it’s violence against females” (43).

“If someone called me a lesbian—in those days all single feminists were assumed to be lesbians—I learned to say, “Thank you.” It disclosed nothing, confused the accuser, conveyed solidarity with women who were lesbians, and made the audience laugh” (51).

“When I was campaigning on the road and meeting with Republican or independent women, what I tried to say was: You didn’t leave your party. Your party left you. Forget about party labels. Just vote on the issues and for candidates who support equality” (47).

Speaking of early-day airline requirements for female flight attendants: “. . . their appearance was prescribed down to age, height, weight (which was governed by regular weigh-ins), hairstyle, makeup (including a single shade of lipstick), skirt length, and other physical requirements that excluded such things as a 'broad nose'—only one of many racist reasons why stewardesses were overwhelmingly white” (89-90).

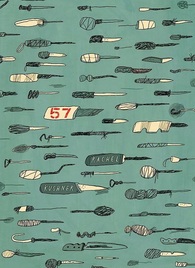

“A journey—whether it’s to the corner grocery or through life—is supposed to have a beginning, middle, and end, right? Well, the road is not like that at all. It’s the very illogic and the juxtaposed differences of the road—combined with our search for meaning—that make travel so addictive” (179).

Or perhaps this sounds familiar: “The name of the Vatican body investigating the nuns is the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the same body that conducted the Inquisition, which came to be known as the Holocaust of Women because as many as eight million women healers and leaders of pre-Christian Europe were killed by torture and burning at the stake over more that five hundred years. Chief among their sins was passing on the knowledge of herbs and abortifacients that allowed women to decide whether and when to give birth” (208).

On the Church’s complicity with slavery: “From 1492 to the end of the Indian Wars, an estimated fifteen million people were killed. A papal bull had instructed Christians to conquer non-Christian countries and either kill all occupants or ‘reduce their persons to perpetual slavery.’ From Africa to the Americas, slavery and genocide were blessed by the church, and riches from the so-called New World shored up the papacy and European monarchs. Whether out of guilt or a justifying belief that the original occupants were not fully human, history was replaced by the myth of almost uninhabited lands” (215).

Quoting Wilma Mankiller, tribal leader: “Wilma said many Native people believed that the earth as a living organism would just one day shrug off the human species that was destroying it—and start over. In a less cataclysmic vision, humans would realize that we are killing our home and each other, and seek out The Way. That’s why Native people were guarding it” (239).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed