A WRITER'S WIT |

New Yorker Fiction 2016

Chloé Poizat

Chloé Poizat Illustrated by Chloé Poizat

NEXT TIME: My Book World

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Chloé Poizat Chloé Poizat October 31 2016, Anne Carson, “Back the Way You Went”: This sparse story is divided into three parts, each, it would seem, tangentially or even obscurely related to the other. ¶ In “Garland,” a woman recovering from loss becomes a bee as her two bee friends, later divorcing, attempt to ease her pain. In “Mexico,” a woman and her elderly mother visit her father, an Alzheimer’s patient, in the facility she refers to as the Last Lap. “Trouble in Paradise,” written in first person from an adult daughter’s point of view, highlights a quiet Christmas she spends with her mother-in-law in Ohio. She ends their dishwashing conversation by saying she’s brought a recording of Lubitsch, presumably a silent film by the German director, known for his avant-garde style. This reference, like Carson’s allusion to Gogol, perfectly suits this story which seems to exist outside of any conventional sense of time. Carson’s second New Yorker story in 2016. Her collection, Float, is out now. Illustrated by Chloé Poizat NEXT TIME: My Book World

0 Comments

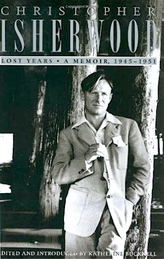

My Book WorldI'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the twenty-first in a series of twenty-four.  Isherwood, Christopher. Lost Years: A Memoir 1945-1951. London: Chatto, 2000. With the completion of this book I’ve now read all 3,069 pages of Isherwood’s diaries. Though he calls this one a memoir, it is a reconstructed diary of the years 1945-1951. In essence, Isherwood keeps two records: a day-to-day account of people he interacts with, major and minor events. In the more expanded Diaries Volumes One – Three, he writes out detailed accounts of events, observations, prejudices, fears about his health, and high and low spots with his lovers, particularly Don Bachardy. In Lost Years, however, Isherwood holds nothing back. Except for changing some names of partners, he tells all about his sex life during these six years. At one point he quietly boasts (or otherwise he would not mention it) that he has had over 400 sex partners (and he’s only in his forties, heh, heh). His pattern in this volume is to list the day-to-day events, and, as of this writing (1973) he combs his (excellent) memory to expound on those events. At the same time, as a heavy drinker, he often admits he can remember little or nothing about things he has written. Still, he does comment on his writing projects, his relationship at the time (a younger man, William Caskey, a photographer), and notes about books he is reading and films he’s worked on as a screenwriter or viewed for entertainment. His prejudices against Jews, the French, and dark-skinned people seem more entrenched than when he is older. Again, is he a victim of his time and place of birth, or does he willfully deny that these prejudices are immature and wrong-headed? In spite of his flaws, I find much to admire in Isherwood: a man who creates, sings, listens to and critiques his own tunes. Opinionated people often become that way because they realize they are correct about so many things, and that reinforcement causes them to be even more opinionated. We trust them. And often we should. Some nuggets: Editor Katherine Bucknell, from her Introduction: “Isherwood never gave up his writing as [Edward] Upward did; for he was a writer above all, not an activist, even when it came to his homosexual kind. By writing in explicit sexual detail about his intimate behavior and that of his close friends and acquaintances in the years immediately following the war, he was portraying the hidden energies and affinities of homosexual men all over the United States who during that period were gathering increasingly in certain, mostly coastal cities as peace and prosperity returned to a country much altered by vast wartime mobilization. This hidden social group, whose consciousness of itself as a group was intensified by the demographic shifts brought about by the war and then extended throughout the 1950s, was to emerge in its own right as a significant force of change in American and in western culture generally during the final third of the twentieth century. Much of this change began in southern California, and Isherwood was living at its source. His personal myth is part of, and in many ways emblematic of, the larger myth of the group to which he belonged: and his reconstruction of his life during the postwar years foretells much of what was to come” (xiv). This statement may have continued to resonate with Isherwood as his life progressed, because he kept an active social (and often sexual) life, rife with smoking and drinking. Though he did finally give up the former, drinking (though he was not a classic alcoholic, often giving it up for weeks or months at a time) to excess remained a part of his life until quite late in life.

Isherwood begins keeping journals when he is a schoolboy and continues during his short time at Cambridge. He continues while living in 1930s pre-Nazi Berlin. After he writes The Berlin Stories, he destroys those diaries, thinking that they have served their purpose, that he’d rather relive his past through his fiction than his journals. However, he lives to regret his decision and spends the rest of his life attempting to document his life. I believe that perhaps these diaries may end up being his true literary legacy. They provide the scaffolding upon which his other twenty or so works rest. And for all his “fumbling,” his is a life truly fulfilled. He both works hard and has a great deal of fun, and he never apologizes for either. NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Eva O'Leary Eva O'Leary October 24, 2016, Ottessa Moshfegh, “An Honest Woman”: Jeb, a man over sixty, acquires a new neighbor, a young woman, and he would like to tickle more than her fancy. ¶ The nameless woman is tough, though, has eyes with two different colors, and says things like “Shit, don’t cry” (63). The author deftly shifts the point of view to the woman on occasion. These clever movements help one to experience her thoughts and feelings so that she isn’t merely the sexual object she’s become in Jeb’s eyes. As she spends a short time drinking with him—like the fly to the spider, in his living room with the front door locked—one senses his continued intent. But she, the girl, in his parlance, is not only too smart to succumb to his crude seductions (funny-tasting whisky) but is also fleet of foot. The she-fly escapes with only the scent of danger remaining in Jeb’s squalid house. No victim here. Moshfegh’s collection, Homesick for Another World, comes out in January. Photography by Eva O’Leary. NEXT TIME: My Book World

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Emiliano Ponzi Emiliano Ponzi October 17, 2016, Cynan Jones, “The Edge of the Shoal”: A man gone fishing in a hidden bay, in his kayak, withstands a storm, has his finger stripped by fish while unconscious, and is weathering yet another event as the story ends. He assesses his situation: “He keeps to hand the thick jumper. Tucks the cagoule in by the seat. Takes a brief inventory of the boat. He does not add: One man. One out of two arms. Four out of ten fingers. No paddle. No torch. One dead phone” (77). Without said paddle he can only count on what he calls the rhythm of the water, perhaps of life—waves and wind that might or might not move him to shore. The more his life is threatened, of course, the more he wants to survive. “Trust the float now. You have to trust the float” (79). Not surprisingly, Jones’ new novel is titled Cove. Illustration by Emiliano Ponzi NEXT TIME: My Book World

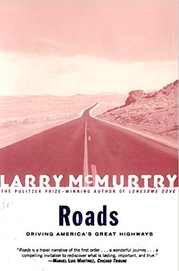

My Book World McMurtry, Larry. Roads: Driving America's Great Highways. New York: Simon, 2001. “I wanted to drive the American roads at the century’s end, to look at the country again, from border to border and beach to beach” (11). With this statement, McMurtry begins his travel book, which is not so much about the places he sees—although he does go into some detail about literary people, places, events—as much as it is about the roads that take him there. McMurtry loves to drive and not along those quaint roads where you can get stuck behind a slow-moving RV or semi, but the big ones, the Interstates. And every road he introduces with the article, t-h-e: the 15, the 40, the 35. He’ll often take a plane to a target city, rent a car, and drive back to his native Archer City in Texas. Some nuggets: “My casual intention, in thinking about these journeys, was to have a look at the literature that had come out of the states I passed through. For Minnesota there is not a whole lot. Scott Fitzgerald, though a native son, spent most of his life east of Princeton or west of Pasadena. His work seems to me to owe little or nothing to the [M]idwest. Louise Erdrich lives in Minneapolis now, but most of her work is set well to the west, near the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota” (30). Once, while with friends in Boise, Idaho, following our attendance of a play set in an outdoor amphitheater, we and our hosts got in the car. I dreaded the wait for all of those vehicles to vacate the huge parking lot (recalling how savagely impolite most Texans are when it comes to their own motto of Drive Friendly), but I was hugely surprised when, at a certain juncture, as if there were a four-way stop, drivers politely took their turns until each car, of the hundreds, had made its way to the exit—all without frenzy, all without rancor or rudeness, and in record time. Surely such a land is not as bad as McMurtry makes out. Think of all the wise academics at Idaho universities. Think of all the Mormons and other religious people who make their homes in Idaho. Are they all to be tainted by a group such as the Aryan Brotherhood? Come on, Larry.

And talk about hatred of government: once when I was on a trip with forty other West Texans to visit the city of Ottawa, Canada, a majority of my fellow travelers booed the very mention of our president’s name. You see, this particular bakery had dared to rename their maple leaf cookie the Obama cookie. I never felt so ashamed to be an American in my life. I personally HATED George W. Bush, but I NEVER would have booed his name in any public setting, particularly in a foreign country—because much as I detested him and his policies, he was still my president. Larry, please, no more generalizations about people who hate or don’t hate. They’re just not relevant. We are all capable of hate in almost any context. I certainly won't let this one slip prevent me from loving your book! NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Carson Ellis Carson Ellis October 10, 2016, Kevin Barry, “Deer Season”: A seventeen-year-old Irish girl sets her sights on an Englishman in his thirties to aid her in parting with her virginity. ¶ The girl’s seduction succeeds, and all seems well until she returns home not long into her first year at university, when her father has learned of her fling: “You were seen!” he explodes. She, in the dark, returns to the man’s leased bungalow, which is now empty, and falls asleep on the kitchen floor. Barry strikes some fine literary tones: a murmuring river, a Roberto Bolaño reference, a coming-of-age theme, and an oblique flirtation with The Scarlet Letter. But, in spite of rich physical detail, something about the story seems thin. The only original aspect may be that the girl goes after him, but in the grand scheme of things, didn’t also Eve? Didn’t Hester Prynne, just a little? The author’s most recent work is Beatlebone, a novel. Illustration by Carson Ellis. NEXT TIME: My Book World

My Book WorldI'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the twentieth in a series of twenty-four.  Isherwood, Christopher. Liberation: Diaries, Volume Three: 1970-1983. New York: Harper, 2012. Having now read Isherwood’s diaries, except for his Lost Years, which is a reconstruction of his life from 1945-1951, I feel, in a sense, that I’ve lived life alongside him. Yes, I believe I can say I’ve lived a parallel life of voyeurism as I’ve read all three diaries (2,681 pages), covering the greater part of his life, right up to his death in 1986. I’ve more or less lived in his house with him, sometimes sharing his bed with some of the (apparently) sexiest men in the world, including his long-time companion, Don Bachardy. I’ve struggled through his writing, as he articulates what he fears are certain problems taking place in the manuscript he is working on at the time. I’ve been to every party he has, where he often, by his own admission, drinks too much—so much so, in fact, that he can’t remember exactly what has happened or whom he’s insulted. I’ve accompanied him every time he strolls along the beach in Santa Monica, California, where he lives, or squabbles with local residents or fusses over a neighbor’s nocturnally barking dog or rascally kids who have no respect for the private bridge that somehow sets their property apart from others. I am exposed to every opinionated thought he holds about other writers, artists, agents, actors, directors, composers or religious leader, and their work. Oh, yes, I’ve suffered through his anguish over not being able to participate in Hinduism as authentically as he wishes, almost daily writing something about his Swami or the monastery or his inability to meditate properly. I’ve sat on the toilet with him as he struggles with the indelicacies of an aging body. I’ve noted his weight, daily, as he records it in his diary and stews over how he can lose even more, while at the same time ingesting great quantities of empty calories found in drink and rich food. I sympathize yet am a bit impatient with his concern over his fading looks. Photos of his youth indicate a stunning gentleman, who, besides being smart, is handsome, and often wins over any body he indeed decides to win over. So as he ages, he must accept it, and does, with a certain reserved grace. In some ways he is an average person with sometimes extraordinary foibles. Though he is highly intelligent, his life seems tinged by racism and classism, perhaps a product of his time and birthright, however hard he otherwise tries to escape them. He drops out of Cambridge University after one year, yet it doesn’t seem to hurt his career. Maybe it only narrows him in some way, although god knows he travels the face of the earth enough to be capable of empathizing with a broad range of peoples. As I near the end of this document, I become a bit bored with his obsessions, particularly with death, since he knows he is going to experience a slow decline from prostate cancer (one of his biggest fears). At the same time, he is able to view his life in a larger context—he’s kept such copious records of it—and make some rather stoic and pithy statements. “I’m not in a good state. Death fears—that’s to say, pangs of foreboding—recur often. They seem to be part of a quite normal physical condition; the pangs of a dying animal, thrilling with dread of the unknown” (686). He writes these words on October 23, 1983, a little over two years before he dies. In spite of the struggle of his last years—all chronicled in this tome—he often lives with a joie de vivre that most of us only hope to experience a few times ever. As I often do, I’ve listed some nuggets from this, the final installment of Christopher Isherwood’s diaries. The following comes under the category of gossip, interesting only because of its noted victims: “The usual pronouncement that Truman Capote is a ‘birdbrain.’ Gore [Vidal] has finished a novel called Two Sisters in which he admits that he and Jack Kerouac went to bed together—or was that in an article? (Gore told me about so many articles he’s written and talks he has given that my memory spins.) Anyhow, Gore now regrets that he didn’t describe the act itself; how they got very drunk and Kerouac said, ‘Why don’t we take a shower?’ and then tried to go down on him but did it very badly, and then they belly rubbed. Next day, Kerouac claimed he remembered nothing; but later, in a bar, yelled out, ‘I’ve blown Gore Vidal!’” (11). As I finish reading the last few pages of this diary and absorb the editor’s statement about Isherwood’s death (1904-1986), I weep a little. Yes, after 2,700 pages of three diaries, I feel in a sense that I have lost a friend. I know, that is so sentimental as to be crap, the sort of thing Isherwood loathes, yet I can’t help it. And he started it! I don’t believe he would have written the diaries and left them to us if he hadn’t wished for us to know him, the good and the bad. And know him I do, at least a little.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Andrew B. Myers Andrew B. Myers October 3, 2016, Etgar Keret, “To the Moon and Back”: A young Israeli father buys a multicopter drone for his six-year-old son and presents it to him the day after his birthday. ¶ Why? Because he’s divorced, and the mother never allows this father to be present on the kid’s birthday. On this day after, this father take his kid to the mall to get batteries for the drone remote, and at some point a cash register becomes a point of contention when the boy, Lidor, wants that for his birthday present—simply because Daddy has said he can have anything in the store as his second present. Later, having given up on the cash register purchase (offering 2,000 shekels), the father and his son fly the drone at the park. The father cajoles his Lidor: “Who loves Lidor the most in the world?” I ask, and Lidor answers, “Daddy!” This story both irritates and delights. You absolutely hate that this father has to perform acrobatics to see his kid and get him to love him, but you love the fact that the father’s willing to perform such acrobatics in order to hear that “killer laugh of his. There’s nothing nicer in this stinking world than the sound of a kid laughing” (65).  READ MY ‘BEHIND THE BOOK’ BLOG SERIES for My Long-Playing Records & Other Stories. In these posts I speak of the creative process I use to write each story. Buy a copy here! Introduction to My Long-Playing Records "My Long-Playing Records" — The Story "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "Ghost Riders" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Blight" "A Gambler's Debt" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Engineer" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "The Age I Am Now" "Bathed in Pink" Listen to My Long-Playing Records Podcasts: "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "My Long-Playing Records" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "Bathed in Pink" Also available on iTunes. |

AUTHOR

Richard Jespers is a writer living in Lubbock, Texas, USA. See my profile at Author Central:

http://amazon.com/author/rjespers Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

Blogroll

Websites

|