A WRITER'S WIT |

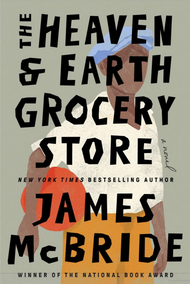

This novel has a well-earned spot on Goodreads.com “Historical Fiction” shortlist for 2023. Early in the twentieth century, in Pottstown, PA, a certain intersectionality occurs between the African Americans, Jewish Americans, and the whites of the town, and, as one can imagine, it isn’t always pretty. The Jewish and the Blacks do all right—they’re both outliers confined to the town’s Chicken Hill neighborhood—but interactions with white citizens are to be guarded, mostly because of past transgressions against minorities. The titular grocery store is the center of Chicken Hill activity for a long time, until the beautiful but lame woman owner dies. Her husband continues to run it, but the establishment is not the same. There are a number of villains, but the main one, a doctor, gets his in the end. And one of the town’s victims, a boy who loses his hearing in a childhood accident, is rescued from an insane asylum and smuggled to South Carolina to live out his life there. McBride has a magnificent story to tell, and he removes himself from it so that just the story remains. All in all, a very satisfying read.

Coming Next:

TUES: A Writer's Wit | Pam Houston

WEDS: A Writer's Wit | David Wong

THURS: A Writer's Wit | Diana Gabaldon

FRI: My Book World | Rachel Maddow, Prequel

RSS Feed

RSS Feed