A WRITER'S WIT |

New Yorker Fiction 2016

Tom Gauld

Tom Gauld Illustrated by Tom Gauld.

NEXT TIME: My Book World

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Tom Gauld Tom Gauld May 30, 2016, Charles Yu, “Fable”: Man goes to therapist to “work through some stuff by telling a story about that stuff” (59). ¶ By retelling story of his life several times in one session—often starting over—man relates to reader story of his life: his careers, his wife, their attempts to have baby, then failure to do so, and then finally, against others’ warnings, they do conceive and have a son, who never quite grows up inside. Yet child is smart enough to know this is so. But fable seems to end without moral, or if there is one, it is feeble: “If this is where your story starts, then so be it” (65). ¶ Writing a fable in this exacting but tedious once-upon-a-time format may be rather like writing a poem using an equally worn-out form. You can still do it, but probably you shouldn’t. Charles Yu’s most recent collection is Sorry Please Thank You, which came out in 2012. Illustrated by Tom Gauld. NEXT TIME: My Book World

0 Comments

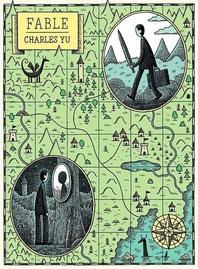

My Book World  Mayer, Jane. Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right. New York: Doubleday, 2016. I haven’t read a more challenging book than this one in a long time—not that the 450-page tome is technically difficult to read (seventy pages are comprised of notes and an index). It is more of a textbook that could very well be studied over the course of an entire semester. Yes, it is the immensity of sickening information washing over me chapter after chapter that makes it difficult to forge ahead. I hear the author speak on C-SPAN’s Book-TV’s “In Depth” series in March (a three-hour interview), and her earnest discussion of not only this book but her entire career convinces me I should soldier through to the end. And at long last, I have. Dark Money begins with the following caveat issued by Louis Brandeis, former Supreme Court justice, which also serves as the book’s epigraph: “We must make our choice. We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.” And thus Mayer breathes life into the premise of her entire book, which she structures into three main sections: Part One, Weaponizing Philanthropy: the War of Ideas, 1970-2008; Part Two, Secret Sponsors: Covert Operations, 2009-2010; and Part Three, Privatizing Politics: Total Combat, 2011-2014. Essentially, for almost fifty years, a few individuals have attempted over and over again to exert political muscle by purchasing it. And since the SCOTUS’s Citizen’s United decision these individuals have succeeded beyond one’s wildest dreams. In Part One, Mayer traces the lives of two of the most politically active Koch brothers, Charles and David, and how the four brothers are raised by their father, Fred Koch, to be ruthless business people. Only two manage to “succeed” to the degree that Charles and David do, but Bill and Freddie snatch their share of their inheritance and create lives for themselves apart from the family. Mayer includes the fact that the elder Fred Koch does business with the Nazis prior to World War II, helping them to build a great capacity for fuel storage. And it isn’t merely a business venture that makes him quite wealthy; Fred actually admires the fascistic elements coming to power in 1930s Europe. This fact helps to establish the ruthlessness that trickles down to Charles and David, the lengths to which either will go to get what he wants. Charles, especially, has the patience of a large feline predator, waiting, restrategizing after defeat to attack again and again until he is victor. Part One also details others who ally themselves with the Kochs: Richard Mellon Scaife, John M. Olin, and the Bradley brothers, Lynde and Harry, how they exploit so-called philanthropy [501(c)(3)s], loopholes to accumulate vast sums of untaxed money and use it illegally for political purposes. Because of limited space, I will not summarize the contents of Parts Two and Three. Mayer weaves together her sources and observations with the icy remove of an experienced and award-winning journalist, but she never wavers from the premise that hugely wealthy individuals are conspiring always to gain power over the lives of ordinary Americans by effecting policy changes in Congress which favor Big Business. And as I do read, I must circle her titular words “dark money” at least a dozen times as she hits home the motif chapter after chapter. Some nuggets worth the reader’s digestion (or indigestion, as the case may be): “Almost all of the recipients [of Bradley Prizes] had played major roles in tugging the American political debate to the right. And almost all had also been supported over the years by a tiny constellation of private foundations filled with tax-deductible gifts from a handful of wealthy reactionaries whose identities and stories very few Americans knew but whose ‘overarching purpose,’ as Joyce [Bradley] said, ‘was to use philanthropy to support a war of ideas’” (119). This might as well be Mayer’s thesis statement. These are Mayer’s last few sentences of the book: “But sharing was never easy for Charles Koch. As a child, he used to tell an unfunny joke. When called upon to split a treat with others, he would say with a wise-guy grin, ‘I just want my fair share—which is all of it’” (378). Indeed.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

Check out my newest story, "Delia's Reunions," published in the most recent issue of VCU's distinguished journal, Blackbird! New Yorker Fiction 2016 Jason Holley Jason Holley May 23, 2016, Lauren Groff, “The Midnight Zone”: The Florida spring break vacation for a family of four is disrupted when the father is called away, and the mother falls and splits her head open. ¶ At this point the first-person narrative from her point of view becomes even more inward: lantern batteries that burn out, increased rainfall, the night lengthening to an eternity, and scores of other impressions that the woman accumulates flat on her back waiting for her husband to return from what he projects to be a forty-eight-hour trip. It isn’t. When he finally does show (a woman has jumped from the building he owns), the mother and two children and dog are lumped into one bed: My husband filled the door. He is a man born to fill doors. I shut my eyes. When I opened them, he was enormous above me. In his face was a thing that made me go quiet inside, made a long slow sizzle creep up my arms from the fingertips, because the thing I read in his face was the worst, it was fear, and it was vast, it was elemental, like the wind itself, like the cold sun I would soon feel on the silk of my pelt (73). Goff’s impressionistic writing is rife throughout the 4,250-word story. One wants to underline most of it, to recall its at once soothing yet unsettling lines. Another one of the her fine stories appeared in the magazine in 2015, and her third novel, Fates and Furies, came out in September. Illustration by Jason Holley.  READ MY ‘BEHIND THE BOOK’ BLOG SERIES for My Long-Playing Records & Other Stories. In these posts I speak of the creative process I use to write each story. Buy a copy here! Introduction to My Long-Playing Records "My Long-Playing Records" — The Story "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "Ghost Riders" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Blight" "A Gambler's Debt" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Engineer" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "The Age I Am Now" "Bathed in Pink" Listen to My Long-Playing Records Podcasts: "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "My Long-Playing Records" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "Bathed in Pink" Also available on iTunes.

My Book World I'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the thirteenth in a series of twenty.  Isherwood, Christopher. The World in the Evening. Minneapolis: U.of Minnesota Press, 1952, 1982. Evening, set in the late 1930s and early 1940s, seems to be hung on a simple frame. Part One is entitled “An End.” In it the protagonist, Stephen Monk, catches his second wife, Jane, in a compromising position with another man and leaves her immediately—almost too easily, it seems. Isherwood introduces a number of principle characters, including Stephen’s “Aunt” Sarah, as well as his nurse, Gerda. Part Two is called “Letters and Life.” In this section Stephen recovers from a horrendous accident which occurs at the end of Part One, in which he is hit by a truck (described rather ethereally with little blood or pain). In this new milieu of body casts and long, empty days of convalescence, Monk untangles his life for the reader (often by way of letters he has saved): he flashes back to the life with his first wife, Elizabeth, a famous author, older than Stephen by twelve years, and how she dies. All of this section takes place in his family home in Pennsylvania which his aunt manages. He also describes an early episode in his married life with Elizabeth in which a younger man inveigles him into having a brief and unsatisfactory affair. In Part Three, “A Beginning,” the reader is brought back to the beginning time period where Stephen’s body is healed, and he ties up all the loose ends of the story. Stephen and his ex-wife Jane have lunch, and the reader finally learns what really happens in the beginning with her and the man she’s with in bed (actually, it’s a large children’s playhouse in the back yard where a party is being given). For some readers (even to Isherwood as a younger man), the novel might conclude a bit sappily, a bit too neatly. The ending is perhaps saved by the witty repartee the couple exchange. For twenty-first century readers, however, it may be a bit too sweet. A few nuggets from the novel: In this passage we read a portion of a letter written by Elizabeth, with regard to Hitler’s rise to power, while she lives in Europe: “Oughtn’t I to be doing something to try to stop the spread of this hate-disease? Oughtn’t I to be attacking it directly? But, of course, this very feeling of guilt and inadequacy is really a symptom of the disease itself. The disease is trying to paralyze you into complete inaction, so it makes you drop your own work and attempt to fight it in some apparently practical way, which is unpractical for you because you aren’t equipped for it—and so you end frustrated and doing nothing” (171). It may remind some of us of how we and the media are paralyzed by a particular presidential candidate at the moment. More so than any book of Isherwood’s that I have read so far, the reading of this one seems to be an academic exercise, not as enjoyable as the previous twelve.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Penelope Umbrico Penelope Umbrico May 16, 2016, Akhil Sharma, “A Life of Adventure and Delight”: Gautama, a twenty-four-year-old Indian graduate student living in New York City, is arrested for hiring a prostitute. ¶ Gautama feels a certain shame, but because his hormonal drive is strong, he continues to search out women. His sources for shame are many: a sister with epilepsy, a disease that makes her unplaceable as a bride in India. He meets an Indian graduate student, Nirmala, and slowly they become involved, even to the point of having sex. Gautama begins to see her faults, and stories of their relationship filter back to the family—disrupting the custom of arranged marriages, jolting forth yet another layer of shame. A year after his arrest, Gautama procures another prostitute, and even though he is delighted with her, he knows tomorrow he will feel shame. Sharma’s earlier New Yorker story, “A Mistake,” is perhaps a stronger, more nuanced narrative of Indian life meshed with the life of an American. Sharma is the author of a novel, Family Life. Photo-Illustration by Penelope Umbrico.  READ MY ‘BEHIND THE BOOK’ BLOG SERIES for My Long-Playing Records & Other Stories. In these posts I speak of the creative process I use to write each story. Buy a copy here! Introduction to My Long-Playing Records "My Long-Playing Records" — The Story "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "Ghost Riders" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Blight" "A Gambler's Debt" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Engineer" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "The Age I Am Now" "Bathed in Pink" Listen to My Long-Playing Records Podcasts: "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "My Long-Playing Records" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "Bathed in Pink" Also available on iTunes.

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Karine Laval Karine Laval May 9, 2016, John L’Heureux, “Three Short Moments in a Long Life”: A man gives a first-person account of three significant episodes in his life. ¶ “The Spy” is concerned with the narrator’s obsession with Beverly LaPlante, a girl in his second-grade class, who disappears until she reappears in the third grade cussing a blue streak because she knows she will die of polio. In “The Writer,” the narrator’s ire over being well-published but poorly compensated for it spills into an encounter with a young man resembling Jesus, who appears at his door asking for a donation. He gives. In “The Substance of Things Hoped For,” the narrator is reduced to being referred to as a “white male, eighty,” by hospital staff when his wife calls 9-1-1. At this point in his life the man has been diagnosed with Parkinsonism, not quite the disease, but not quite free of it either. He and his wife conspire together to end his life by not ever calling 9-1-1 again: “I say, ‘I’ll miss you when I’m dead.’ And in a while there comes the final moment: the earth stops turning and a luminous silence descends. And then, as we draw one last breath together, I snatch your hand. And hold it. Holding it, and holding it, and still holding it, I breathe out. You can’t write more profoundly than that about dying of a dread disease. At least I don’t think you can. L’Heureux’s The Medici Boy came out in 2014. Photography by Karine Laval.  READ MY ‘BEHIND THE BOOK’ BLOG SERIES for My Long-Playing Records & Other Stories. In these posts I speak of the creative process I use to write each story. Buy a copy here! Introduction to My Long-Playing Records "My Long-Playing Records" — The Story "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "Ghost Riders" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Blight" "A Gambler's Debt" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Engineer" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "The Age I Am Now" "Bathed in Pink" Listen to My Long-Playing Records Podcasts: "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "My Long-Playing Records" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "Bathed in Pink" Also available on iTunes.

New Yorker Fiction 2016  Eleni Kalorkoti Eleni Kalorkoti May 2, 2016, Alexandra Kleeman, “Choking Victim”: Karen, thirty-two, is a young urban mother who leaves her six-month-old infant with a strange but friendly woman, so that Karen can return a few blocks and retrieve an expensive stroller which becomes unnavigable when it loses a wheel. ¶ With short stories, titles mean everything. In “Choking Victim,” we sight a victim immediately, an old man who succumbs to a terrible coughing fit in the apartment next door. Then he survives. As mother Karen and babe Lila stroll through the city—before the stroller becomes unhinged—one expects the baby to choke somehow. But no. After the accident, Karen and Lila abandon the heavy, expensive pram and alight in a café, where the friendly woman offers to sit with Lila so Karen can return for the stroller. In addition to exploring the issue of trust, this story helps us creep through the suffocating life of a new mother, whose husband is away on business for two weeks. “She felt as if she were deep underwater, desperately stroking up toward the surface, toward light and air. She had no idea how far away it might be” (65). Finally, we see that Karen is perhaps the real choking victim here! When she runs into a college friend in a store where she’s buying Band-Aids for her beleaguered feet, the friend’s questions remind her that she is a writer with a successful professional life having nothing to do with a baby who isn’t even forming words yet. Karen is so enamored with this man’s attentions that she lingers longer than she probably should. As she returns to the café, we expect something awful to have happened. Kidnapping comes to mind. But no, worse. Blue and red lights of police cars illuminate the face of her baby, who’s been abandoned a second time—this time by Linda, the friendly woman. The entire last paragraph moves at a glacial pace—and with good reason—because the narrative has entered the mind of the infant, who seems entirely unmoved by the event. Kleeman’s story collection, Intimations, is out in September. Illustration by Eleni Kalorkoti. NEXT TIME: My Book World  READ MY ‘BEHIND THE BOOK’ BLOG SERIES for My Long-Playing Records & Other Stories. In these posts I speak of the creative process I use to write each story. Buy a copy here! Introduction to My Long-Playing Records "My Long-Playing Records" — The Story "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "Ghost Riders" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Blight" "A Gambler's Debt" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Engineer" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "The Age I Am Now" "Bathed in Pink" Listen to My Long-Playing Records Podcasts: "A Certain Kind of Mischief" "The Best Mud" "Handy to Some" "Tales of the Millerettes" "Men at Sea" "My Long-Playing Records" "Basketball Is Not a Drug" "Snarked" "Killing Lorenzo" "Bathed in Pink" Also available on iTunes. |

AUTHOR

Richard Jespers is a writer living in Lubbock, Texas, USA. See my profile at Author Central:

http://amazon.com/author/rjespers Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

Blogroll

Websites

|