A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

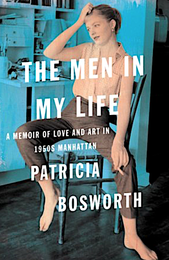

For the same reasons I enjoyed reading her biography Montgomery Clift years ago, I sucked down Patricia Bosworth’s memoir of her own life. She is not afraid to search out and write the truth of any situation and do it with dignity and empathy for involved parties. Because for about a decade she is an actor, she becomes acquainted with Montgomery Clift personally, and she approaches her subject with honesty and a certain kindness. The same can be said for her book: all of the members of her family are loved ones, but they are also, at times, bad actors who undermine her life. Her father is a narcissistic alcoholic attorney, a closeted homosexual (according to her mother) whose love is not entirely unconditional; he profoundly affects Patricia’s life when he commits suicide. Her mother is a published novelist (Strumpet Wind) whose career stalls and becomes an ambitious stage mother who plays on all Patricia’s insecurities: Patricia’s actions and achievements are never good enough. The relationship that affects Bosworth the most, perhaps, is her brother, Bart.

When they are young they establish a special bond, with even their own form of Pig Latin which their parents cannot understand; they share that language for many years until Bart ceases to think it appropriate. A particularly effective tool peppered throughout the book are her continued conversations with Bart’s ghost. Eerie how she makes it seem as if he’s still alive as he advises her. In his teens, her brother is attracted to males and has sex with a couple of them, including a friend at an exclusive boys’ boarding school. There, after they are discovered together, the friend commits suicide, an act from which Bart never recovers. He, too, eventually kills himself before reaching the age of twenty-one. Bosworth’s father and brother are not the only men she writes about in her page-turner; she outlines in detail her love (and sexual) relationships with several different men, including two husbands.

She reminisces about her acting career in which she appears on Broadway with the likes of Daniel Massey and Elaine Stritch. The highlight of this period may be when she appears with Audrey Hepburn in a film, The Nun’s Story. Nonetheless, in spite of Bosworth’s success on the stage, she comes to the realization that she can no longer bare her soul in that manner but must establish a writing career instead. And glad we are that she does. Bosworth’s book—taken from her diaries, her notes, but most of all her remembrances—is a stunning read.

[I’m still amazed in this day and age how a book produced by one of the top companies in the country can make it through all that scrutiny with a typo:

“I was able to slip into the wings just as Bobby begain [sic] belting out ‘I Believe in You,’ the signature number” (350).

How many copyeditors overlooked this error and how many times? How many times did the author or her staff herself read the galleys? Amazing.]

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed