A WRITER'S WIT |

New Yorker Fiction 2016

Blaise Cepis

Blaise Cepis Photo-Illustration by Blaise Cepis.

NEXT TIME: My Book World

New Yorker Fiction 2016  Blaise Cepis Blaise Cepis August 1, 2016, Joshua Ferris, “The Abandonment”: A popular television actor believes his wife has left him when she doesn’t immediately return to their New York apartment from buying Sunday morning bagels and a newspaper. ¶ Nick spends hours searching for her, even tosses his cell phone in the trash in frustration and then can’t recall the correct ashcan when he returns to retrieve it. In the next scene, however, he takes a car to Brooklyn and visits with a married female artist he’s met four days earlier at an important opening in midtown. In this tête-à-tête they compare their lives—Ferris makes a point of having them compare the scents of their lives—and they end up making out. When they finally determine that Nick must leave before her husband and family return, he passes by the rowdy bunch on his way to the elevator. Back in Manhattan, Nick’s wife has to open the door for him because his key no longer seems to work. The reader now becomes privy to information that Nick has done this before: left her momentarily because of his abandonment issues. So the reader is left with sort of an O. Henry / F. Scott Fitzgerald magazine-story irony that hinges on one factor. If this wife of his, Naomi, had taken her cell phone with her—even to pick up bagels, this woman who only too well knows what her husband’s abandonment issues are—then there would be no story, no magazine irony. In today’s world no person under forty abandons her phone, even for a short errand, especially in Manhattan. What if Nick should want to change his bagel order or want something else? What if I’m molested? This point seems to demand a greater than normal suspension of disbelief. Ferris is the author of To Rise Again at a Decent Hour, which came out in 2015. Photo-Illustration by Blaise Cepis. NEXT TIME: My Book World

0 Comments

I'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the fifteenth in a series of twenty-four. My Book World Isherwood, Christopher. Down There on a Visit. New York: Avon, (1959) 1978. I first read this novel in 1980 on my way back from a trip to Europe. I marked very little, and, frankly, I don’t think I understood much of what Isherwood was talking about. I hadn’t yet studied literature in depth. I hadn’t studied Buddhism or the act of meditation. It meant little to me. This reading seemed richer, especially in light of the fact that I’ve read almost all the author’s works including his thousand-page Diaries, Volume One, 1939-60. One of the main characters of Isherwood’s novel, Paul, scoffs at the character named Christopher Isherwood by saying: “You know, you really are a tourist, to your bones. I bet you’re always sending postcards with ‘Down here on a visit’ on them. That’s the story of your life . . . . (308). So, in effect, the novel is a threading together of four visits down there. “Mr. Lancaster” begins in London, in 1928, when the character Isherwood is twenty-three and takes a voyage to northern Germany by way of a tramp steamer called the Coriolanus. He does this courtesy of one Mr. Lancaster, who becomes both like a father and a son to Isherwood. Lancaster dies at his own hands, it is conjectured, because of his impotence. And another character, Waldemar, makes his first appearance in the book, this section, which seems more like a short story than a novel segment. The second part of the novel is “Ambrose,” a former mate of Isherwood’s at Cambridge (one supposes W. H. Auden is the model), who buys property on a Greek island, St. Gregory, and is in the process of building a house in this 1930 segment. He invites Isherwood and his Berliner companion, Waldemar, to venture down to visit. The only other inhabitants of the island are some scamps who, though working as laborers on the new house, also get into a lot of mischief as they head to the mainland each night. The island is rife with snakes, flies, and a host of other problems that probably only young men could tolerate. Yet the place is not without its charms: “When we have eaten supper, we sit out in front of the huts, at the kitchen table, around the lamp, unhurriedly getting drunk. As soon as the lamp has been placed on the table, this becomes the center of the world. There is no one else, you feel, anywhere. Overhead, right across the sky, the Milky Way is like a cloud of firelit steam. After the short, furious sunset breeze, it gets so still that the night doesn’t seem external; it’s more like being in a huge room without a ceiling” (85). The Ambrose story seems to chronicle the then universal loneliness of the homosexual. Now, however, since we are such a liberated group derived from such a liberated society, there exists is no such thing, right?

The “Waldemar” section of the novel is set in 1938 and begins on another boat, this time outside the Dover Harbour. Isherwood, the man, the author, has just returned from his 1938 trip to China with Auden. In this section, Auden is again the model for a different character, Hugh Weston. As character Isherwood and companion Dorothy step off the boat, whom should they run into but Waldemar! There would be no such thing called a novel without the idea of coincidence. Isherwood is terribly concerned with the concept of class and is horrified when on a visit to his family, they treat Waldemar as a low-class ragamuffin, instead of their son’s dear friend. Christopher is also very concerned with the lead-up to war in Germany. Waldemar begs Christoph to take him with him to the US, but Christopher says it is impossible. Yet Waldemar reappears once again! In “Paul,” the fourth and final part of his novel, Isherwood moves to Los Angeles, the time 1940. He connects with a male prostitute, a gorgeous, highly paid young man who is really difficult to get to know, but Christopher tries. This section reflects Isherwood’s attempts to achieve a spiritual life by way of Buddhism. He makes an acquaintance with a swami, Augustus Parr, and, when Paul indicates that he would like to become more spiritual, the two connect, spend almost an entire day together. This section wears thin before the end, in which Paul, winds up returning to Europe and dying essentially of drug usage. Isherwood, the author, does a little too much deus ex machina to make things turn out easily for him, instead of allowing the story to end with a bit more conflict or complexity. I think Down There on a Visit is in actually a collection of long stories more than it is a novel. Just because you refer to a character that appears earlier does not make it a novel. Even if Waldemar keeps reappearing in all four parts, one cannot necessarily call this work a novel. A novel is one large sweep of motion, with one climax. This one has four for each part, and then the author has, with great skill threaded the four of them together. I’m not criticizing the execution, exactly. I’m just saying it should have been sold as linked stories (though such a thing had not yet been marketed by the publishers at that time) or four novellas, but not as a novel. That said, one cannot praise Isherwood enough for his sense of lyricism and competence with the English language. They are always superb. NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Keith Negley Keith Negley July 25, 2016, Joy Williams, “Stuff”: Henry, aged sixty-three and columnist for a newspaper called Zephyr, learns from his doctor that he has lung cancer and a short time to live. ¶ This information comes to him by way of a sour irony when the doctor apparently sees he is staring at the file of a “Henry” who is eighty-five: “‘You have lung cancer as well, a bit more advanced, actually.’ The doctor stared at him again. ‘Sorry about the mixup’” (55). The mixup! Really? Befuddled, Henry buys an enormous Christmas tree, but when he can’t get into his assigned parking slot at his condo, he tears off to visit his 100-year-old mother living in a facility he refers to as Ambiance. The caregivers there blow off a bit of steam by sticking their heads in a patient’s door and asking, “Who’s the President? Who’s the President?” Williams’s characters have a way of saying two things at once: “‘It may be one of those rolling heart attacks. Won’t kill you but makes you queasy. But, on a lighter note, here’s my question: Do you think there’s a moral weight to our actions?’” (59). The character speaking here, Henry’s mother, is most probably not the one asking the question—it is actually author Williams—but because it is attributed to Henry’s mother, the question ends up being both profound and dull. When Henry says it is time for him to leave, one feels he is not talking about getting in his car with the Xmas tree stuffed in it. Likewise, when his mother asks him if he will be able to find his way out, she is not speaking entirely of the entrance/exit of a place called Ambiance. Williams’s collection, 99 Stories of God, came out this month.

Illustrated by Keith Negley. NEXT TIME: My Book World

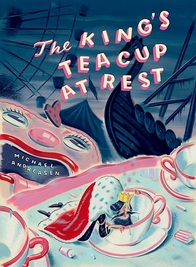

New Yorker Fiction 2016  Ryan Heshka Ryan Heshka July 11 and 18, 2016, Michael Andreasen, “The King’s Teacup at Rest”: The King of Retired Amusements purchases Liebling’s Sunday Morning Carnival to add to his collection. He is accompanied by his retinue—a steward, a boy scout, and a dancing bear—as they inspect his new acquisition. They begin with the hot dog stand where the king is warned against eating one of the green wieners with rancid relish and mustard. They shift to the Cul-de-sac of Fun, to the Fun House, to the Full Tilt, and finally to the teacups, where the king rests after disgorging his hot dog decision. The story seems to be an intricately constructed mini-allegory, in which certain abstractions are signified by decaying imagery of abandoned amusement parks. To say any more would spoil your reading fun. Andreasen is one of the magazine’s few writers with no major book to his credit. Yet! Quite a coup to get published by the New Yorker without a new title to hawk! Illustration by Ryan Heshka. NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016 - Look for it 7/25/16! While I'm on a brief hiatus, please feel free to read previous posts from the ARCHIVES located to your right.  Kazi Kazi And . . . if you like photography of dogs, you might consider visiting the gallery at Texas Tech University's International Cultural Center to peruse its annual "Putting on the Dog: Dogs without Borders" Exhibition. Yours truly has a print of one fine Borzoi named "Kazi" hanging on the wall. Now through 8/25.

New Yorker Fiction 2016 Horacio Salinas Horacio Salinas July 4, 2016, T. Coraghessan Boyle, “The Fugitive”: Twenty-three-year-old Marciano, a gardener’s assistant in southern California, is a multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis patient who refuses to take his meds and rest. ¶ To eke out a living, Marciano must trap varmints for his boss Rudy and drown them while still in their cages. However, because of his lowly status (documented but can’t prove it), Marciano is treated by the state-regulated medical system as a criminal—and because he breaks his agreement to rest by returning to work and by entering public places without wearing his mask. He is caught and returned to the clinic where, by spitting into the faces of the medical workers, he escapes once again. The story closes with Marciano trapped in a grassy corner of a neighbor’s yard, where he intends to rest his head for only a moment: “He closed his eyes. And when he opened them again all he could see was the glint of a metal trap, bubbles rising in the clear cold water, and the hands of the animal fighting to get out” (59). This final predicament is like being trapped in one of Rudy’s varmint cages as it is dropped into a garbage can full of water. Only this time the trap is his own ribcage, his own lungs, being drowned by his own poisonous mucus. The metaphor is apt if a bit too obvious. And a better title—“The Weight of It”—might be buried in the author’s text on page 58. Boyle’s novel, The Terranauts, is out in October.

Photograph by Horacio Salinas. NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016 |

AUTHOR

Richard Jespers is a writer living in Lubbock, Texas, USA. See my profile at Author Central:

http://amazon.com/author/rjespers Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

Blogroll

Websites

|