A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

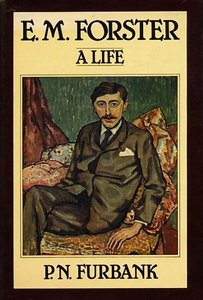

New York: Harcourt, 1977.

After reading Christopher Isherwood’s entire oeuvre in 2015-6 and seeing what an influence Forster had been on the man, I felt compelled to read this Forster biography, as well. Isherwood credits Forster with, among other things, providing him with a creative mantra: Get on with your own work; behave as if you were immortal. Isherwood reminds himself, page after page in his journals, that he must remain industrious. Since Furbank does not provide a complete list of Forster’s titles but offers them up in the narrative (and index) instead, it is difficult to realize that Forster, too, produced a broad variety of works, well over twenty. So, a generation apart, Forster provides the model for Isherwood’s ethic. They seem to share similar ideas on literary quality, standards, a certain fussiness in regard to everything. Yet there exist differences between the two men born a generation apart.

Forster, though he does write about sex between men, does not allow it to be seen, particularly Maurice (which is written in 1913-4 but published posthumously in 1971 and made into an Ivory-Merchant film, in 1987) until after his death. Though he becomes sexually active with men at one point, it is not to the degree, I believe, that Isherwood does, the latter claiming to have had over four hundred partners, and yet sharing his last thirty-three years with one man. Forster is never able to find that one man, though I believe he would have liked to. He did have close emotional relationships with other men, but they were mostly married, and in no way did he wish to interfere with those, or gay friends to whom he was not physically attracted, such as his peer, J. R. Ackerley. Isherwood made a break with British culture by making his home in America in 1938-9. Though well-traveled throughout the world, and though he empathized with a great many others, Forster’s being was too deeply rooted in Britain ever to leave. Just the story of the home he lived in with his mother for so many years is enough to complete this picture. When finally vacating West Hackhurst, a rather large estate, it takes the man many months to categorize all the collections of things that had come down to him, and, that as an only child, he now must be rid of: decades, if not centuries, of useless family letters and documents, furniture, clothing, carpets, dishes, art.

Nuggets:

Personal writing of Forster, in which he goads himself to improve his lot:

(1) Get up earlier, out of bed by 9 (2) Smoke in public: it gives a reason for you & you can observe unchallenged (3) try to plan out work, at least by the week (4) more exercise: keep the brutes quiet (5) don’t ever shrink from self analysis, but don’t keep on it too long (6) get a less superficial idea of women (7) don’t be so afraid of going into strange places or company, & be a fool more frequently (8) keep accounts (122).

Here Forster expresses his dismay with how most British authors treat point of view in novels :

A different kind of difficulty was that he had come to feel bored with orthodox fictional form. He told Dickinson (8 May 1922) that he was tired of the convention that one must view the action through the mind of one of the characters. If you can pretend you can get inside one character, why not pretend it about all the characters? I see why. The illusion of life may vanish, and the creator degenerate into the showman. Yet some change of the sort must be made. The studied ignorance of novelists grows wearisome (II, 106).

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed