A WRITER'S WIT |

New Yorker Fiction 2016

Cornett | Doyle

Cornett | Doyle “Our lives, he says, were always entwined. We talked over everything a thousand times, read the same books, lived through and shared so much, and in some curious way our thoughts, our imaginations fused to such an extent that we ended up writing the same novel, more or less” (67).

This story might have been written by F. Scott Fitzgerald, even O. Henry, or perhaps John Cheever—fitting quite well into the New Yorker schemata of publishing particular stories that blend accessibility with a certain blandness of predictability. All fine writers, McEwan included, are capable of producing such an animal. Question is: should they? McEwan’s latest book is The Children Act.

Photography by Grant Cornett

Illustration by Stephen Doyle

NEXT TIME: My Book World

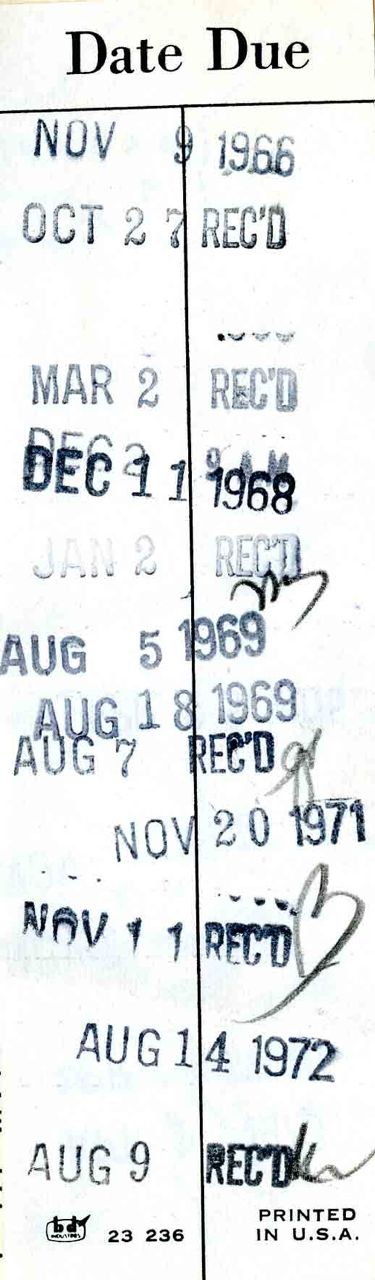

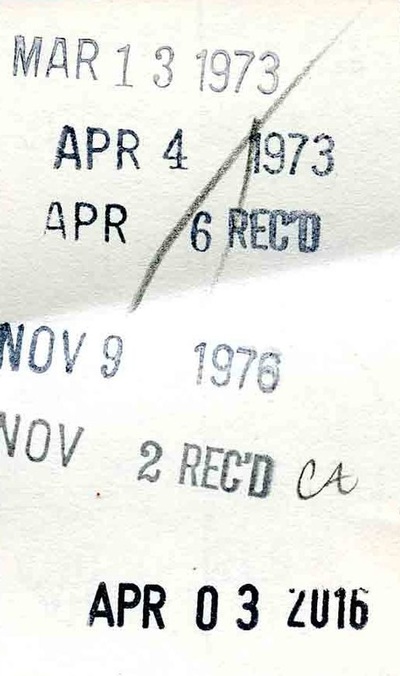

Introduction to My Long-Playing Records

"My Long-Playing Records" — The Story

"A Certain Kind of Mischief"

"Ghost Riders"

"The Best Mud"

"Handy to Some"

"Blight"

"A Gambler's Debt"

"Tales of the Millerettes"

"Men at Sea"

"Basketball Is Not a Drug"

"Engineer"

"Snarked"

"Killing Lorenzo"

"The Age I Am Now"

"Bathed in Pink"

Listen to My Long-Playing Records Podcasts:

"A Certain Kind of Mischief"

"The Best Mud"

"Handy to Some"

"Tales of the Millerettes"

"Men at Sea"

"My Long-Playing Records"

"Basketball Is Not a Drug"

"Snarked"

"Killing Lorenzo"

"Bathed in Pink"

Also available on iTunes.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed