All My Antique Valentines

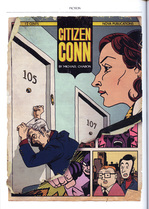

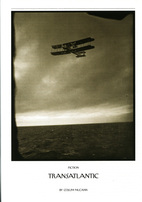

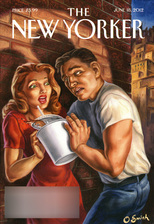

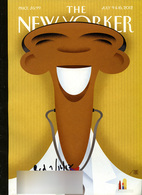

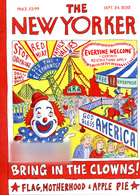

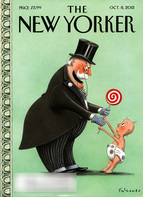

All My Antique Valentines  I've said this before, but my mother saved everything. In this case she collected scores of Valentine cards from the 1920s and 1930s. I posted them on a bulletin board when I taught sixth grade in the seventies and eighties. Even then they were antiques, but the kids seemed to enjoy them. I don't know about Valentine cards today, but these rely heavily on the pun. A number of them have moving parts. Most of them have a good sense of design and plenty of RED. I share them once again with all you grown-up kids out there!  On Saturday, January 19th, the Texas Tech University art department held its annual 5x7 event, auctioning off five-by-seven inch works produced by TTU faculty, past and present, as well as alumni. Chair Joe Arrendondo, as usual, did a fine job of pulling the event together. The proceeds, substantial in the past, will go toward scholarships for art students. This year's suggested dress was 60s Mod or Colorful Cocktail, and everyone seemed to get into the spirit of the event. Take a look. A Little History Last year I read every New Yorker short story published in 2011—all forty-nine—and made a close reading of each one. If interested, the reader can access that post by viewing the side bar and clicking on “January 2011." By comparison to this year, it was a rather colorless presentation, but I found the process of collating the information quite interesting. At the time, I chose to read all those stories so that I might “uncover the apparent secrets of placing one’s story in the magazine. What elements make a work so perfect, so alluring, that the New Yorker staff would have no choice but to snatch it up?” I snottily challenged myself to see if I could unleash the secrets of being one of the select few to publish in that venue. Secondarily, I wondered if I could finish the project without screaming. I did. And I’ve returned for more. This time I used the same worksheet as last year. From those fifty worksheets, I came up with the following figures. Just the Stats, Man . . . Ma'am LENGTH The New Yorker story for 2012 was an average length of 6,000 words (from 1,000 to 12,000). Most writers were male, sixty-eight percent, higher by one percent than last year, in fact, while females comprised the complementary thirty-two percent (yet on par with previous years). YOUNGER AUTHORS The average writer was fifty—nine years younger than last year’s average. (I did not calculate the age of the writers published posthumously; F. Scott Fitzgerald would now be over 116. Jeez.) Four of the writers were so young or crafty at avoiding Google’s long arm that their ages could not be easily documented—only their gloriously Googled photographs (one way of documenting their youth). CENTRAL CASTING I determined that sixty-two percent of the protagonists/central characters were male, thirty-eight percent, female—allowing for considerably more female protagonists this year. Yet is literary sexism really on the decline? STRAIGHT AS A NAIL Ninety-eight percent of the protagonists/central characters were apparently heterosexual and one percent apparently LGBT—even lower than last year’s five percent. Do gays not live and breathe in such rarefied air? Can they not establish a place at the New Yorker table of fiction, when such a large population of writers lives in NYC? Sixty-eight percent of the lead characters were apparently Caucasian, twenty-eight percent “minority” or foreign, and four percent apparently Jewish or Israeli. ERAS One story seemed to be set in the 1910s, two in the 1930s, one in the 1950s, two in the 1960s, five in the 1970s, one each in the 1980s and 1990s, five in the recent aughts, twenty in the current teens (using contextual clues such as contemporary electronic devices to confirm), and as many as eight from an undetermined time period including three with futuristic settings. Others may argue, and they are free to post their own findings. GEOGRAPHY A majority of the stories were set in the United States: ten in New York, five in something-glorious-about Montana, two in Texas (both are Antonya Nelson’s stories, which are set in that primeval swamp-with-skyscrapers better known as Houston), two in California, and one each in Connecticut, Georgia, Missouri, Massachusetts, Nebraska, and Arizona. Six stories were set in the UK, three stories in Israel, two each in Canada and Russia, and one each in France, South America, Switzerland, Haiti, Pakistan, and China. Sixty-four percent of the stories took place in urban or suburban settings, while twenty-eight percent happened in rural or pastoral settings. Six percent seemed to wander into both. HARD HITTERS In 2012, Junoz Díaz published three stories in the magazine; T. Coraghessan Boyle, Thomas McGuane, Alice Munro, Antonya Nelson, Jonathan Lethem, and Maile Meloy published two apiece. Not fair, not fair, not fair. Their double-dipping aced out eight other writers. ART OF LANGUAGE With regard to language, eighty percent of the writers appeared to use English in a more or less traditional manner. I’m talking about sentences that moved elegantly from one to the next, aided by an expansive vocabulary and an impeccable sense of word choice—with little experimentation or stretching of the language. Eight percent seemed to use experimental or nonstandard English: those who did stretch the language, pulling it in the direction the author wished, using diction indicative of a particular subculture or ethnic group yet doing so without depicting stereotypes. And twelve percent had rather a mixed usage of the traditional and non-traditional. A TENSE POINT OF VIEW Twenty-six percent of the writers employed the first-person point of view, while a strong sixty-two percent used the third person, the long-accepted mode for storytelling in our culture. Eight percent used second person almost exclusively throughout their stories. Eighty percent used the past tense, and eighteen percent used the present tense; two percent began in one tense and shifted to a second or third tense throughout. Interpretive Dance THEME For 2012, I challenged myself to distill the theme of each story to one word if I could: ALIENATION, thirty-eight percent; LOVE, fourteen percent; LOSS, six percent; ALIENATION OF WAR, EPHEMERAL NATURE OF LIFE, FREEDOM, and SEXUAL MORES, four percent each; MODERN LIFE, FORGIVENESS, ACCEPTANCE, CONQUERING OF NATURE, ALTERNATE REALITIES, DESIRE, FRIENDSHIP & LOYALTY, POVERTY, ATONEMENT, LIFE VS. DEATH, COMING OF AGE, HONOR, and GRIEF, two percent each. EASY READING? Even more so than last year, I determined that the New Yorker story must definitely be accessible. While many of the magazine’s non-fiction articles are “challenging,” particularly if you’re reading in a field that is not yours, the short stories are not necessarily as complex as those found in top literary magazines. And perhaps that is the point. The editors want their readers to enjoy the fiction, to be entertained by it—as if it were one of their cartoons. Only longer. Like last year, I determined that a New Yorker story must strike the proper balance between urbanity and childish wonder. Some Nuts and BoltsONE COMMA, TWO COMMAS, THREE In my opinion, the New Yorker style sheet accounts for far too many commas. The editor acts like a teen who just can’t decide how many and where to put them. Only the commas are carefully placed—with the editor setting off every subordinate clause in the second part of a sentence even though it isn’t always needed in order to be clear (most grammar experts offer such a comma as an option). That and other tedious practices make it seem as if many of the stories are written by the same author. I understand it makes for clean reading, but when it comes to fiction, might the writers have a bit more of a say about punctuation? POOR CIRCULATION? The right people will never read these words, but I also have a bone to pick with circulation. The hard copy of my New Yorker often arrives a week or even ten days past the cover date! In the old days, I subscribed through the University Subscription Service, and they consistently delivered it the Friday before the cover date, in time to make the cartoon contest deadline. Considering that I now also receive a digital copy that the magazine delivers to my iPhone a week before the cover date (as part of my regular subscription rate), the hard copy is rendered somewhat irrelevant. I love the deeper analysis of articles found in a weekly magazine compared to those found in most newspapers, but receiving the issue as late as three weeks after the events being analyzed have occurred makes it truly irrelevant. HERE WE GO Below the reader will find a short analysis of each story ranked in three categories--as well as links to biographical information (if author's name is highlighted in yellow), to the magazine for more information (sometimes the story itself), or to more works by a particular author. Top of the Heap  Jashar Awan, Artist Jashar Awan, Artist 1. February 13 & 20, 2012, Michael Chabon, “Citizen Conn”: An old man seeks to right a wrong with Feather, a former professional partner and friend, and obtain forgiveness—but never succeeds. ¶ One of the longer New Yorker stories, reminiscent of an Alice Munro saga. Luxurious. Unfolding every crinkled corner of these two men's lives. And the reader is not disappointed. Although Artie Conn never receives forgiveness for his sin (he had made a deal that signed away their rights to comic book characters they had created together—without Feather’s knowledge), Artie does finally realize how valuable their friendship had been to Feather and how Artie’s error, his betrayal, could never be forgiven. Chabon is author of Wonder Boys.  Cover by Roz Chast Cover by Roz Chast 2. March 5, 2012, Alice Munro, “Haven”: A teenage girl in 1970s Canada travels to live with a childless aunt and uncle near Toronto and learns a certain tolerance (the character’s age, in part, limits the sophistication of her knowledge). ¶ Munro is such a master. She begins in the past tense, luring the reader in. Then at a certain point—a position that could almost be a climax but isn’t—she shifts to the present tense. Why? one wonders. But it is perfect timing—only the most prescient reader (not this reviewer) will be able to predict what is going to happen at the funeral of the uncle’s sister, from whom he has been estranged for many years. When he is stopped by the choir entering the main aisle, the Anglican way—an entrapment of his own design—one sees it is a snare in more than one way. A beautiful, subtle, and effective symbol. One must read Munro's Selected Stories.  Photo by Dan Winters Photo by Dan Winters 3. April 16, 2012, Colum McCann, “Transatlantic”: Following World War I, two men cross the Atlantic for the first time in history. ¶ This may be the magazine’s most exciting story of the year. A moment-by-moment account of this flight, the story is an earth-shattering feat written largely in fragments or short, choppy sentences, much like the sea beneath the men’s wings. They experience rain, ice, snow. Batteries that heat their seats fail mid-flight. The men are cold, cold, cold. The plane gets “lost” in a cloud. It falls, falls, falls. They pull out of it. A blue sky is where the clouds should be and vice versa. They right themselves and land in a bog. Little people, growing larger every second, run out to greet them and their beleaguered craft. The last sentence of the story is “Ireland.” Transatlantic will be published as a novel in June 2013.  Cover by Chris Ware Cover by Chris Ware 4. May 7, 2012, Louise Erdrich, “Nero”: A child visits her grandparents and is awed by a dog that, in the same fashion as a man in town, is never quite tamed until he is shot. ¶ Erdrich develops a wonderful parallel between a wild dog and a wild man, both “tamed” by a wild but peaceful man, Uncle Jurgen. Erdrich’s prose is so unique yet gives the impression someone might really have thought the words: “There were always bits of wood or metal jutting out on which Nero could gain purchase” (61). Her narratives possess a certain mystical quality, in this case tying the world of humans and the world of the wild into one: “But it is probably impossible for our two species, interdependent since the dim beginning of our ascendancy on this earth, not to communicate” (61). The reviewer's favorite of Erdrich's titles: The Master Butchers Singing Club.  Photo By Dan Winters Photo By Dan Winters 5. June 4 & 11, 2012, Sam Lipsyte, “The Republic of Empathy”: In six parts the story tells of one man’s life, as five other characters reveal it. ¶ In “William,” the man's wife Peg wants to have a second child. His friend Gregory (a gay ex-cop, hardly qualifying as a principal LGBT character) and he witness a man falling off the next building; he speaks of his friend, an artist who paints for the movies. In “Danny,” Gregory’s son tells his side. In “Leon & Fresko,” the reader meets the two men who had been seen fighting on the roof in “William.” In “Zach,” a hedge fund manager meets Gregory. In “Drone Sister,” the sci-fi scene appearing in script form, William is shot down, making him toast, literally. In “Peg,” William’s widow laments to her German teacher, Arno, who says of William’s death, “They don’t make mistakes.” The structure of this story is clever and easy to follow (a mainstay of a New Yorker story). What is really enjoyable are the tones that Lipsyte captures, the current I-care-about-the-world-but-I’m-not-sure-any-of-us-can-do-anything-about-it attitude. Sarcastic. Mellow. Callous. All at different turns in the narrative. All sincere at the time. And all dead-on.  Cover by Owen Smith Cover by Owen Smith 6. June 18, 2012, Ben Lerner, “The Golden Vanity”: A young Manhattanite opts for “twilight” sedation during the extraction of all his wisdom teeth. ¶ This choice seems to be a metaphor for two realities that haunt this man’s life. Should he select the local anesthetic or the fuller-bodied sedation, a more golden one that enhances his thinking as a successful author? Lerner may be one of the smartest and most lyrical authors the magazine has chosen to showcase. He creates many a lovely turn of phrase: “He was suffused with warmth; the universe was benevolent, the lamp positioned to shine into his mouth was the nourishing sun” (73). ¶ Only someone the reviewer's age could note how easily a young writer assimilates today’s electronics into his fiction. Cell-phone screens. Streaming TV episodes on one’s laptop. Someone who knows little of the “before,” Lerner takes on an intellectual yet lyrical journey through the “road-not-taken” realities mixed with roads that are taken: his man experiences both the local and the twilight sedations. One that bars his physical feeling only, the other barring all feeling but creating a beautiful, memorable world . . . if he could only remember it. A lovely and complex story. One of the best of the youngish writers.  Cover by Bob Staake Cover by Bob Staake 7. July 9 & 16, 2012, Tessa Hadley, “An Abduction”: A teenage girl is picked up in her neighborhood by three boys, one of whom Jane later submits to sexually because he’s handsome and desirable. ¶ Hadley—almost as if she were Charles Dickens—shifts the point of view all over the map, making it, more or less, an omniscient point of view. It’s so appealing, gliding from Jane briefly to her father, then the three boys in their cars as they drive her to Nigel’s house (the abduction), back to Jane, to Nigel, to handsome Daniel watching over Jane like a vulture before he takes her sexually, to Fiona, briefly, as she later sees Jane’s discarded swimsuit on her bathroom floor, back to Jane upon waking the next morning to see that Daniel and Fiona have spent the night together, to Jane in her late fifties on her shrink’s couch, to Daniel, a lawyer in Zurich, where the omniscient narrator informs the reader Daniel now remembers nothing about Jane, how he’d engaged sexually with a fifteen-year-old girl in the 1960s. He now recalls nothing. ¶ American writers are taught by precept and example NOT to shift the point of view (or “head hop,” as some teachers say), or to use a fully omniscient point of view, but here the practice is quite serviceable. The story could have been told no other way. As the Brit Hadley says in an online New Yorker interview: “I needed the framing omniscient narrative, which is almost fairy-tale-like, or perhaps like a crime report.” Hear, hear. Hadley lives in Cardiff, Wales. One should read her Accidents in the Home.  Cover by Frank Viva Cover by Frank Viva 8. August 6, 2012, F. Scott Fitzgerald, “Thank You for the Light” (1936): A woman who sells corsets is transferred from Ohio to Kansas City and is looked upon as a leper because she smokes. ¶ A master Fitzgerald is. A thousand words, and he completely snookers the reader into believing she’s in another world. Details, selective details limn this working woman who, in the 1930s, loves to smoke cigarettes. She loves them so much she enters a church late at night to get a light from the votive candles a sexton is just now putting out. He says, “I guess you came here to pray” (63). And she does, falls into sort of a trance, and when she comes to, her cigarette has been lit. She kneels and says, “Thank you for the light” (63). Light. Light. Light. Is it the sexton (who had left) or . . . . You make the call. Youths of all ages should read Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby.  Cover by Roz Chast Cover by Roz Chast 9. September 24, 2012, Mohsin Hamid, "The Third-Born": This story is one of the New Yorker’s most enjoyable of 2012. Hamid lulls the reader into a trance with his consistent drone of using the second person—removing the narrator from the customary stance of first or third person. ¶ It seems, at first, to be an arcless narrative, a rambling story in which a poor, poor family moves from the squalor of the countryside to the slightly reduced squalor of a large (one assumes) Pakistani city. But there is indeed a climax—subtle though it is—when the second-person narrator realizes he will be the one member in his family to break free from their poverty. He doesn’t know when, but any child that knows twelve times twelve is 144 (and not 134 as his teacher asserts) cannot be destined for misfortune. Forty-year-old author of The Reluctant Fundamentalist.  Cover by Ian Falconer Cover by Ian Falconer 10. October 8, 2012, Lara Vapnyar, “Fischer vs. Spassky”: A Russian woman, a nurse, who has come to the United States, recalls the chess match between Fischer and Spassky in 1972 and how her life turns on Fischer’s win. ¶ Everyone should love this story—so straightforward and yet with little bits of symbolism (never quite perfect). Fischer represents the West, freedom. Spassky, the opposite. When Fischer wins, it means their small family will emigrate to the U.S. Within a year, Marina’s husband will die; she will raise two children alone in a strange country. Yet, to repeat, such symbolism is not perfect. Fischer, it turns out, is crazy—a mean little bastard—and that is unforgivable in the West. Spassky, the Soviet, is a “decent guy,” who stands and applauds Fischer on his concession of the sixth game. No, symbolism is never perfect. Another forty-year-old author. Vapnyar is the author of Memoirs of a Muse.  Art by Martin Ansin Art by Martin Ansin 11. October 15, 2012, George Saunders, “The Semplica-Girl Diaries”: In the future, a family man keeps diary (for future readers) of his family’s experience of using Semplica Girls to adorn their yard. ¶ Loved this story. So crazy. Family man keeping diary. Some sentences, no verb. Others, no subject. Few articles. “So young. Looks like should be working at Wendy’s” (73). Some time in future people will landscape lawns with the living poor, yes, poor women from places like Somalia. Couple buys four SG’s for their yard, on the occasion of their eldest daughter’s BD party (father had won $10,000 in scratch-off). Younger daughter—altruistic one—releases the four SG’s in the night, causing a row, not to mention a huge financial difficulty. Seems that if SG’s not located, will cost man nearly $9,000 in compensation to SG leasing company. ¶ Biting satire set in near future (or is one already there?)—one that, as per Saunders, causes one to ponder. Or should. One should read the author's Pastoralia.  Art by Victo Ngai Art by Victo Ngai 12. October 22, 2012, Callan Wink, “Breatharians”: August, a Montana farm boy, is hired by his father to kill the hundreds of cats that have overtaken their barn. ¶ An admirable story written by a young man of twenty-five—yet with a previous New Yorker story under his belt (see January 2011). So many quirky ideas that serve as metaphor. August inside a metal shed when it’s raining: “He thought it was like being a small creature trapped inside a percussion instrument” (63); “tangled intestines of machinery” (63). Both of these images echo the overbearing presence of the cats. ¶ “Fingers linger” (67). Has one ever seen “fingers linger” used together before—such a perfect rhyme of sound and meaning? The way August’s mother (living in a house on the same property, separate from him and his father) fashions a poncho out of an old quilt and is probably naked underneath it (and crazy, perhaps dying). But the story’s most important task reveals how this boy’s world has unraveled in the last year, and, by killing hundreds of cats with antifreeze-laced milk, he begins to make sense of the substance's innate treachery. His beloved birth-dog, Skylar had accidentally licked antifreeze oozing from a container, and the substance that killed something he loved becomes the substance that kills something evil he hates—even if he doesn’t know what it is.  Art by Karine Laval Art by Karine Laval 13. November 12, 2012, David Gilbert, “Member/Guest”: One of the reviewer's favorites of the year. Beckett, a fourteen-year-old girl, negotiates the tricky waters of an exclusive Long Island Country Club that didn’t exist prior to eighty years ago. ¶ Who doesn’t like to understand . . . be let in on . . . the ways of the upper classes? Holden Caulfield sneering at the adult world. Phineas, upper-midler wannabe before he is shaken from that tree and breaks his neck. The entirely closed yet vacuous world ruled by arcane languages that only the elite seem to understand. Beckett has it all figured out, who’s the cunt in their little ensemble, until she spots her erstwhile friend’s blood in the water and then . . . . Absens haeres no erit. The reviewer’s high school Latin would not unlock this and so he Googled it: “The absent one will not be heir . . . .” Though the story is “about” fourteen-year-old Becket, isn’t it really about any person, anywhere, who, if she can get a leg up on someone, will let loose with a good long stream of piss? David Gilbert is difficult to locate using Google—too many of them—but his work is worth the wait.  Art by Tomer Hanuka Art by Tomer Hanuka 14. June 25, 2012, Shani Boianjiu, “Means of Suppressing Demonstrations”: Lea, an Israeli checkpoint soldier, is “confronted” by three young Palestinians (one is thirteen) who want to have their “demonstration” suppressed, so that it will make a splash in the major papers. ¶ This story is a satiric yet serious look at the Israeli conflict on the West Bank. That three young Palestinians wish to be “suppressed” for purposes of their cause appearing in the newspaper is funny. It illustrates, or seems to, the inanity of the conflict. That with a few negotiations—like whether to suppress a demonstration with shock, tear gas, rubber bullets, or live fire—the conflict could be ended! Thus, a young writer must point out the elephant present, the one that has been gaining weight since 1948. Boianjiu writes with the wisdom of someone much older—like Moses. That everyone else in her country could catch up with her, oh, yes, please catch up.  Art by Paul Rogers Art by Paul Rogers 15. August 27, 2012, Alice Munro, “Amundsen”: A woman travels to a TB sanitarium to teach and becomes involved with a doctor, who wants to marry her but backs out at the last minute. ¶ You could look at the length of this story (10,000+ words) and groan, but then once you begin to read you are ensnared in Munro’s world of ice and snow, drafty rooms, smelly winter clothing that never really dries out—and you’re there with her. Munro’s plots always seem as if they’ll be rather straightforward, but then you find yourself—along with the protagonist—wondering how you found yourself in such a strange predicament. Her stories are the perfect model for compressing a lifetime into ten or twelve thousand words. She’s a master at making such poetic prose.  Photo by Eric Ogden Photo by Eric Ogden 16. December 10, 2012, Steven Millhauser, “A Voice in the Night”: The author spins three tales, twined together, alternating sections I, II, III: Samuel of the scriptures; a boy of the 1950s; the boy’s old-man persona as a writer in the aughts. ¶ Millhauser skillfully creates the texture of Samuel’s Biblical world, the boy’s 1950s world in suburban Connecticut, including the stone bridges of the Merritt Parkway, the contemporary insomnia of the old man recalling the sleeplessness of the other two personas. So much is summoned by the author: the boy’s atheist-Jewish father, Christmas each year but with no religious images, just lots of presents under the tree, a father-teacher whom the son respects. Brooklyn. Literature is recalled like good-friend stories. Know them well. The last sentence: “Soon we’ll all sleep” (77). Samuel, the boy, the author eternally. Millhauser’s story from 2011 was on my “Top” list last year. One should read his Portrait of a Romantic. Middle of the Pile Cover by Barry Blitt Cover by Barry Blitt 17. January 2, 2012, Etgar Keret, “Creative Writing”: Aviad’s wife Maya takes a creative writing course following a miscarriage and writes three stories. ¶ Aviad takes a creative writing course and writes about a fish that becomes a man. Each of Maya’s three stories seems to be symbolic of the couple’s relationship: in one narrative people can only see the people they really love. In another story a woman gives birth to a cat the husband suspects isn’t his. Aviad thinks that is funny, but the story turns “sad” when the cat and the husband don’t get along. The cat says, in meow, “Daddy.” Keret compresses a great deal into 1,600 words: three shorter narratives plus the tension between Aviad and Maya. Do you love me? Should we even have children? It’s a good thing the baby didn’t live.  Cover by Bruce McCall Cover by Bruce McCall 18. January 9, 2012, John Lanchester, “Expectations”: A rich, though overextended British banker does not receive the huge Christmas bonus he’d been expecting and will now find himself under a crush of debt. ¶ His wife chooses this time to leave him for a few days (and perhaps forever). This story is reminiscent of John Cheever’s exposés of urban life in the 1950s USA, and Lanchester similarly lampoons a youngish couple who’ve become mired in the trappings of an upper-class life: nannies, expensive homes, cars, clothing, “spoilt” children. It is also reminiscent of films made in the thirties with men and women dressed in silk robes and clamping cigarette holders between their gritted teeth. Wickedly funny, the story is a parable for our times. Be careful what you wish for and all that rot. A man who wears “bespoke” suits can’t be all good.  Art by Zohar Lazar Art by Zohar Lazar 19. January 16, 2012, Saïd Sayrafiezadeh, “A Brief Encounter with the Enemy”: A young American is part of a contemporary war—somewhere unknown, quite "generic"—and does virtually nothing for twelve months, putting in his time until his stint is over. ¶ You don’t eat, don’t sleep, don’t think, don’t shit. You just act—doing what you’ve been trained to do. This soldier makes it through almost an entire year of boring tedium and on his last day . . . he sees the enemy and shoots him. Or is it the enemy, a man in his fifties, and his dog? Or is it a goat? Oh, no, it’s a boy who also winds up in a pool of blood. The next day the soldier returns home as planned.  Photo, Jacques Henric Photo, Jacques Henric 20. January 23, 2012, Roberto Bolaño, “Labyrinth”: Eight people in a photograph, and the author tells a short story about them—separately and connected. ¶ The narrative seems as if it’s suspended—told in the present tense and quite fluidly—like a slide under a microscope. Eight people pictured in Paris in 1977. Some are married, some not. Some fuck each others’ wives as the photo is “unfrozen” by the author. It is an interesting exercise—and that’s what it could feel like to the reader. The author takes an old photo (he knows no one in it), and he dreams up a narrative that seems plausible. Maybe such an approach is cultural. Bolaño feels free to pursue such a structure, and North Americans do not. And yet a strangely likeable story emerges—so alive and erotic—in spite of its frozen, photographic nature. One of the deceased authors in 2012’s collection, thus edging out a living writer. Perhaps there was no better contemporary story to take its place.  Cover by George Booth Cover by George Booth 21. January 30, 2012, Alice McDermott, “Someone”: In the 1930s, a young girl is courted by a hobbled young man until he announces one day that he’s marrying his boss’s daughter. ¶ McDermott compels the reader to walk down the sidewalk as her character Marie tries to figure out what’s just happened: a crippled boy who’d appeared to propose to her (Would you someday like to get married?); how he’d taken her to a nice restaurant to break up with her; his inadequate vision; the redemptive walk she takes with her brother, an ex-priest, in which he answers her question, “Who’s going to love me?” He says, “Someone. Someone will.” This is a true New Yorker story: accessible yet complex enough to make one contemplate its metaphors, its fine images.  Photo by Stephen Shore Photo by Stephen Shore 22. February 27, 2012, Thomas McGuane, “A Prairie Girl”: Mary, forced out of prostitution, marries a gay man (the only gay principal in 2012’s stories) who later comes to own the family bank. ¶ Except for using the omniscient “trick” of the author/storyteller slipping into first person plural (“our”), the author relates the story in third person. McGuane creates a timeless story. It could be fifty years ago or longer. No cell phones. No TV’s mentioned. More than that, he deals with the issues all American communities deal with: morality of having a prostitute in the community or family; dealing with a gay family member. But most of all, the story is a tribute to the pioneer woman, who did what was necessary to keep her life in order. Trusting a man was not always an option.  Cover by Ivan Brunetti Cover by Ivan Brunetti 23. March 19, 2012, Rivka Galchen, “Appreciation”: A long yet compressed story of a mother and daughter—most likely Jewish, eh?—who play a game of emotional cat and mouse. ¶ You have to love some of the younger writers. Long, long paragraphs apparently not on the same topic. Long words: fungibility (being of such nature or kind as to be freely exchangeable or replaceable, in whole or in part, for another of like nature or level), nonfungibility. Long sections on how a manipulating mother controls the life of her unappreciative daughter, who, in particular, doesn’t appreciate her mother’s long periods of manipulation that have lasted way into the daughter’s thirties. You have to love how the author captures this love-hate, cat-mouse relationship that most probably will not change over the next thirty years. The daughter may or may not grieve over the mother who has spent a long period of time controlling her daughter’s life. And it all comes down to money, which, according to the scriptures, is the root of all evil. Another one of Galchen's stories just apppeared in the magazine's January 7th issue!  Art by Steve Powers Art by Steve Powers 24. April 2, 2012, Victor Lodato, “P.E.”: A father arrives in Tucson from New Jersey, and his now obese son puts him up for a couple of weeks. ¶ P.E. = Parallel Energetics = There is another “you.” Lodato has the new idiom down pat, but the reader musn’t be fooled. He is a complex storyteller, or a teller of complex stories, and he doesn’t dwell on what traditional writers might: the mother who hanged herself when he was seven. He concentrates on the character’s own hell: his obesity, the premise of P.E., that there exist several realities within his one life, that they sort of connect like freeways, and that he can join any one he wants at any time—except that he can’t, not really. Poor Freddy, a Gen Yer, is just like all the poor slobs of previous centuries who were abused in some way by life—mother’s suicide, drugs, obesity—and there is little he can do about it except create his parallel reality and move on like those in previous centuries.  Art by Annette Marnat Art by Annette Marnat 25. April 30, 2012, Ian McEwan, “Hand on the Shoulder”: A woman looks back at an affair she had as a twenty-one-year-old with an older professor, who prepared her to enter the world of espionage. ¶ As always, the narrative, like most of McEwan’s writing, is spellbinding: the infinite amount of detail, the feeling you’re really inside this woman’s head; his original way with language: “The quaint hiss and crackle of the blunted needle as it gently rose and fell with the warp of the album sounded like ether, through which the dead were hopelessly calling to us” (61). In a way this passage is emblematic of the entire story, as McEwan attempts to bring alive the 1970s in a similar fashion for today’s reader. ¶ The end . . . the end is disquieting, abrupt. The last two sentences are flat, completely unnecessary. The story should end two sentences earlier: “I saw his brake lights come on as he slowed to join the traffic. Then he was gone, and it was over” (65). Finito. That is the real ending, not this: “Two days later, I attended the interview and was accepted. Tony Canning delivered me to my career, but I never saw him again” (65). The reader knows that; the two have just had a fight. The reader does not need to be retold in such stark terms. ¶ One should read any novel of McEwan’s, particularly Atonement.  Art by Victo Ngai Art by Victo Ngai 26. May 14, 2012, Peter Stamm, “Sweet Dreams”: A young couple live in a small apartment located above a restaurant, and after the woman sees a man staring at her on the bus, she later learns he’s a writer basing a story on a young couple he had seen on the bus. ¶ Perhaps one of the clearest translations the magazine has ever published—in the sense that there are no cultural puzzles that the reader must ponder. In fact, the narrative seems simple and straightforward. A certain significance arrives at the end when the woman is flipping through the TV stations and recognizes the writer as “the man from the bus.” He claims, during the interview, that he hadn’t written about the couple that he’d seen; they had only given him an idea. Yes, it turns out he hadn’t been watching them at all. His interview would play for a month on an endless loop, “as imaginary a figure as Lara or Simon” (111).  Cover by Bob Staake Cover by Bob Staake 27. May 21, 2012, Maile Meloy, “The Proxy Marriage”: A Montana couple meet in high school, and the boy falls for the girl but not vice versa. ¶ As a favor to her father, they begin to participate in proxy marriages for American soldiers in the Middle East. They attend separate grad schools, the girl marries someone else, and she then divorces him. After one final proxy marriage, they kiss—connect—and then marry each other. Only a young person could have written this story, easily incorporating the use of texting and Skyping naturally—as if they are a part of daily life. And they are. Meloy covers a great deal of time in her short story, and yet the reader follows her because of the markers she provides. When one finishes the story, one is almost surprised to wind up in such an innocent spot. His red ears. Her lack of awareness that he’d always loved her. After all the proxies, they’re now going to experience the real thing. You’re just sure of it.  Dan Winters / Brendan Monroe Dan Winters / Brendan Monroe 28. June 4 & 11, 2012, Jennifer Egan, “Black Box”: The black box, ostensibly a robot, seems also to be quite human as she takes direction from an unseen power or force. ¶ Egan is clever in the way that she plays with forms on the page. In her novel, A Visit from the Goon Squad, she writes an entire chapter using flow charts. She divides this story into forty-seven boxes, combining human forces with robotic features, or is it vice versa? It is hard to tell if she’s being satiric, but it appears so. There’s a certain sensuality she appeals to: “metallic, like a warm hand clutching pennies” (86). At the same time, this human black box (called a “beauty,” a woman) has robotic capabilities, a sort of “smart human being” (à la smart phone): “Pressing your left thumb (if right-handed) against your left middle finger begins recording” (88). The black box’s eye is also a camera; a flash is detonated by pressing the end of one’s eyebrow. Never do so in the presence of others. Yes, Egan is satirizing the technocraticization of our humanity or, wait, is it the humanization of our technocracy? In fifty years you may be better able to tell. Or not. One should read her novel A Visit from the Goon Squad (see my Reading Journal for 2012’s review).  Photo by Dan Winters Photo by Dan Winters 29. June 4 & 11, 2012, Junot Díaz, “Monstro”: Apocalyptic, post-apocalyptic, or futuristic (or must one choose only one?) tale set in Haiti about a disease that won’t quit—in a world where the globe is so warm the seas are dry already (if one reads correctly). ¶ Díaz is a courageous and noble writer who tackles the big ones here: global warming, incest, race, ethnicity, hubris, the emptiness of wealth—while fucking around (excuse me, experimenting) with language. Mixing Spanish (is it?) and English with futuristic glypts (like text messages, only faster, probably). All of his characters are viktims (as he spells it). The greatest feat of this story is that it manages to keep the reader at arm’s length by way of an emotional distance that is immeasurable in terms of words. Is that the way of all futuristic literature? The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao was a NY Times bestseller.  Jim Krantz/Gallery Stock Jim Krantz/Gallery Stock 30. July 2, 2012, Paul La Farge, “Another life”: A married man attends a birthday party for his father-in-law, leaves early under the guise of feeling bad, returns to his hotel, and, instead of going to bed, eventually hooks up with a pretty barmaid in the bathroom of yet a different bar, after she gets off work. ¶ This is one of those stories in which the dialogue is not set off by quotation marks. You can tell which character is speaking only by his or her idiolect—and you don’t really notice. It also makes the story seem less real, in a sense, as if it’s occurring only in the inside of the reader’s head. Hard to say what’s unusual about this story, if anything—except that this man desires “another life.” ¶ This narrative is more about “alienation” than “freedom.” The husband is so removed from his life, his wife, his family, the fact that they are childless—that when he has his way with the pretty barmaid, he becomes even more alienated. He’s left alone on an icy park bench, probably having a heart episode that may or may not kill him, thinking that his wife who left “to get her shawl,” is probably fucking the “sleazebag” who’d been sitting with him at the bar. Dying all alone on an icy park bench after being inside the vagina of a young, warm barmaid thirty minutes early—that’s alienation.  Art by Jeffrey Decoster Art by Jeffrey Decoster 31. July 23, 2012, Junot Díaz, “The Cheater’s Guide to Love”: The looonnnggg story of an academic from the Dominican Republic who loses the woman he’s cheated on and never wins back. ¶ Okay, this time the reviewer decided to look up every Spanish word he didn’t know—using either his Spanish-English dictionary or by googling it. Díaz’s Spanish must be Dominican, which may be his point. Go with it. Use the context. Don’t look it up! ¶ This is one of those lengthy stories—it could be developed into a novel—that is also compressed like a poem. ¶ A creative writing professor at Harvard is discriminated against by whites he encounters after he cheats on the love of his life and she dumps him. His back pain (stenosis) is a metaphor for the psychic pain he suffers for being such a shit to his fiancée. He realizes in the end: “. . . sometimes a start is all we get” (69). ¶ Díaz’s story is one of three to be published in the magazine this year. One has to wonder why he seems to be so privileged.  Art by R. Kikuo Johnson Art by R. Kikuo Johnson 32. July 30, 2012, Zadie Smith, “Permission to Enter”: Two small girls—one black, one white—grow up in London and later attend university together. ¶ Smith’s penchant for breaking this story into sixty-seven parts is sometimes distracting—as if each one is a separate narrative of its own importance. At the same time, each is inextricably linked with the one before it and the one to follow, as well as with all the others. Smith provides a very interesting view of what it must have been like for a bright black girl to grow up in an England that was finally opening its arms to a world it had pillaged but now invited to feast at its ever-shrinking shores. It is an exciting world for anyone who can ford its many streams. Natalie Blake, the little black girl, is one of these fortunate ones. Smith has published at least five stories in The New Yorker.  Cover by Ian Falconer Cover by Ian Falconer 33. September 10, 2012, Thomas McGuane, “The Casserole”: A man and wife cross the Missouri River on a ferry to visit his in-laws only to discover that his wife is leaving him so she can inherit her family’s ranch alone. ¶ A simple story—all the clues are there—but you don’t see that the man’s wife is going to dump him until the mother-in-law hands him the casserole in a lunch box. As the narrator says, “What kind of idiot puts a casserole in a lunch pail” (94)? ¶ The couple had decided to remain childless. Does the woman now want the ranch? Does she now wish to have a child late in life? The story engenders as many questions as it answers, making McGuane a master storyteller.  Cover by Chris Ware Cover by Chris Ware 34. September 17, 2012, Leonid Tsypkin, “The Last Few Kilometres”: A man in Moscow commutes home on a train while pondering the mistress he has just now left forever. ¶ Written in 1972 when the author was forty-six, this story’s landscape is as arid, bereft as one always imagines Russia to be during the Cold War. And yet there is a trickle of emotion the reader senses as this nameless man sees his mistress for the last time. One witnesses much of the blackness from the train window but not the scene in which he leaves her. And one doesn’t need to see their parting. ¶ The third deceased writer of the year, a translation, no less (see my rant about translations in last year’s post).  Martin Ansin / Birthe Piontek Martin Ansin / Birthe Piontek 35. October 1, 2012, Tony Earley, “Jack and the Mad Dog”: This is a fairy tale of Jack, that Jack, and how he meets his comeuppance. ¶ You can forget that a story is like a triap . . . that it is a trip. You don’t want to take such a trip when you figure out where you’re headed, but once you’re on the road, you’re enchanted. A dog that says, “Ow,” when Jack sits on it. A man named Jack who tells a row of corn, “Go shuck yourself.” A story of witches, of milkmaids Jack has wronged, and the eternal price he must now pay by way of the mad black dog.  Art by Jashar Awan Art by Jashar Awan 36. October 29 & November 5, 2012, Kevin Barry, “Ox Mountain Death Song”: Canavan, a woman masher of twenty-nine, has cancer, and is pursued by Sergeant Brown, who eventually pushes Canavan over a cliff. ¶ Ah, legend, the Irish are loved for it, aren’t they? Canavan’s sexual prowess, his sexual hunger, his brutality, are legendary. And Sergeant Brown—nearing his retirement age of sixty-five—must bring Canavan down before he leaves. And he does (in the space of 3,000 words). ¶ Barry’s use of language is delicious: “. . . and the first thing the Sergeant did was hit him the slap of a phone book across the back of his head” (105). No one but an Irishman could have written that sentence.  Art by Silja Gotz Art by Silja Gotz 37. November 19, 2012, Maile Meloy, “Demeter”: A divorced couple share their only daughter, each having custody for half the year. ¶ Almost contrived as the earthly Demeter chooses to share her daughter half the year with her ex-husband. Yet there are some otherworldly moments in the story—particularly Demeter’s “walking on water” scene at the end, transcending age as well as physics—in which she transcends her earthly pain to become, for a short time, a goddess.  Tim Klein / Gallery Stock Tim Klein / Gallery Stock 38. November 26, 2012, Mo Yan, “Bull”: Lao Lin insults the narrator’s father by pissing on money his father has earned, but his father tames a bull and also conquers Lao Lin in the process. ¶ What seems like an old-world tale is reformulated into a more modern setting that includes, among other elements, formaldehyde that is pumped into meat to "preserve" it. The translation is one of those in which much beyond the plot does not seem to survive. Could one be missing the subtle metaphors: the bull itself, perhaps, representing the blustery Lao Lin? Or perhaps the story is what it appears to be: a morality tale extolling the virtues of honor regardless of what may happen to the protagonist.  Jocelyn Lee Jocelyn Lee 39. December 17, 2012, Marisa Silver, “Creatures”: James’s three-year-old son is expelled from nursery school for aggressive behavior, and this event triggers James’s memory of accidentally shooting his childhood friend’s father. ¶ James’s attitude toward his son’s aggression is born of his experiences of having killed a man. Even in the end, he isn’t sure whether the gun had fired or whether he had fired the gun. His attitude toward his son, who wants a gun, who wants to be aggressive, is protective. James can’t afford to overreact either way. But he does. He will pull his son out of that school. He will let his son enjoy guns even if he, James, abhors them. The magazine’s cover date is three days after the shootings in Newtown, Connecticut.  Art by Scott Musgrove Art by Scott Musgrove 40. December 24 & 31, 2012, Thomas Pierce, “Shirley Temple Three”: Tommy is host of an Atlanta cable TV show that “clones” prehistoric animals (“Back from Extinction”), and he brings a tiny mammoth to his mother’s house to hide (instead of euthanizing it as is the show’s “rule”). ¶ Interesting bit of creative fiction here: some sci-fi mixed with a bit of the spiritual, a bit of the comic opera, the macabre . . . and what do you get? You aren’t sure. You shouldn’t fuck around with mother nature? Some parallel between Mawmaw and Tommy (she’d almost had an abortion because Tommy’s father was married to someone else) and Tommy and Shirley Temple Three, the tiny mammoth? A very odd story—the last one of the year. It’s hard to feel anything for Tommy, Mawmaw, or the tiny mammoth. And what’s that golden light at the end of the story, so bright no one can stand it? The rapture? Mawmaw’s trip to heaven? You just aren’t sure, and that bothers you, when you can’t figure out the ending of a story. Stories Least Liked and Why Art by Brian Cronin Art by Brian Cronin 41. February 6, 2012, T. Coraghessan Boyle, “Los Gigantes”: In a South American country, a giant man agrees (for payment) to breed with many women, but then later seeks to escape . . . and does. ¶ Boyle seems to crank out one of these after another, one novel after another—but the quality is becoming uneven. This story is very intriguing at first. Giants! A foreign country that wants to breed them as well as small people—for entirely different purposes. The giant escapes from the breeding compound twice but only succeeds a third time when the building fails. Very deus ex machina. The ending is a little facile, too—the nameless giant digging his way out of the rubble to live with his love, Rosa, with whom he is now to have a child of his own and not the state’s. Symptomatic of Boyle’s fading powers? Hope not. ¶ One should read his novel The Inner Circle, his portrayal of Kinsey, author of the infamous sex study.  Art by Josh Cochran Art by Josh Cochran 42. March 12, 2012, Donald Antrim, “Ever Since”: A young man whose girlfriend has rejected him attends a cocktail party for an author associated with his “new” girlfriend’s publishing firm, but he keeps thinking of his old girlfriend. ¶ Ah, heterosexual men. There can never be enough stories about the one that got away—in this case, Rachel—whom the reader never learns much about, nor Sarah, the current one toward whom Jonathan only feels a little warmth, nothing strong enough to marry. At the party they search the huge terrace, for someone with a cigarette. Funny. They keep searching—thinking, for example, that smokers might be gathered at the back stairwell. “Aw, fuck,” Jonathan says, when they find the stairwell empty. Finally, later in the evening, one of Sarah’s colleagues indicates he has a cigarette. Ah, success! But then Jonathan pulls a joint out of his pocket—eschewing the cigarette he’s been pursuing all evening . . . . Rather like the perfect girl he’s been chasing, ostensibly, for years and years. One hopes that this is Antrim’s idea, anyway, that some heterosexual men haven’t the slightest idea what they want, in smoking products or women. Even when they’re placed in front of them! Otherwise, what is the porpoise of this here story?  Art by Emily Shur Art by Emily Shur 43. March 26, 2012, Antonya Nelson, “Chapter Two”: A woman named Hil attends AA meetings at various locations in Houston and tells stories of her neighbor as if they are Hil’s stories; she often stops off at a bar afterward. ¶ Though Nelson’s narratives are well developed, warm even, one can find them lacking at times. Because of the intricate structure, one wants more, more depth, perhaps. She sets up “complicated” or “complex” relationships, yet they don’t turn out being relevant necessarily. What’s their significance? ¶ But the story is cute. The premise that an AA member can end meetings by stopping off at a bar could play tragically, but in this story it turns out to be cute. Or wait, maybe going to AA is just a way for Hil to socialize with other losers and make herself feel ta home. Hard to say. One should read Nelson's story collection, Female Trouble.  Art by Martin Ansin Art by Martin Ansin 44. April 9, 2012, Jonathan Lethem, “The Porn Critic”: Dude works at a porn shop and writes reviews for a “newsletter,” and a rich female friend of his convinces two women to come to his apartment. ¶ There exists a real distance here between Kromer and the other characters, between Kromer and the reader. Perhaps that is Lethem’s purpose: just as sex for its own sake can separate participants emotionally, a story “about” porn can separate the reader from any vicarious “enjoyment” that a story about sex might bring. Dang.  Art by Kristian Hammerstad Art by Kristian Hammerstad 45. April 23, 2012, Junot Díaz, “Miss Lora”: A sixteen-year-old brother of a boy who dies of cancer pursues the dead boy’s former girl friend. ¶ This is a difficult story because of the amount of Spanish and its crucial nature to understanding the story. Even when you put certain words and phrases in Google Translate, all you get back is gibberish. It is instructive for English-only readers to know how Spanish speakers/readers must feel living in a country that expects them to speak or write English only.  Art by Matthew Bollinger Art by Matthew Bollinger 46. May 28, 2012, Lorrie Moore, “Referential”: A woman loses her “deranged son” to an institution as well as the man she’s lived with for ten years. ¶ This is not one of Lorrie Moore's wittier stories. It’s terribly straightforward and tough. When the older couple visit their deranged son, the woman decides she’d like to bring him home. Pete, not really the son’s father, gives no opinion. ¶ Via a cute caller-ID trick, Moore clues the reader that Pete probably has another woman. What one really sees is the ragged alienation of modern life. Children with mental diseases. Women with few resources. Men with no drive or commitment. And not a shred of humor. ¶ If you’ve never read it, you need to look up Moore’s short story (one of the top one hundred of the twentieth century as selected by John Updike) entitled, “You’re Ugly, Too.” Mean and hilarious.  Photo by Dan Winters Photo by Dan Winters 47. June 4 & 11, 2012, Jonathan Lethem, “My Internet”: A human tells of his or her own private Internet. ¶ Odd story. The author takes a thousand words to say essentially the same thing over and over again. It is clever by half. You, as the reader, do feel as if you’re trapped in (both) Internets, his and yours—with him—as if you're inside a bank vault and the air you share is diminishing by the second.  Cover by Ian Falconer Cover by Ian Falconer 48. August 13 & 20, 2012, Justin Taylor, “After Ellen”: A young man leaves his girl friend, intends to stay with his sister, but winds up living in the San Francisco area instead. ¶ Yes, another young writer references iPhones and laptops as a matter of course (like a writer used to reference landlines, one’s grandparents’ party line, telegrams). Though Scott is compulsive, often ordering the same item multiple days from the same restaurant menu—he is searching for something different. Different than the non-Jewish girl, Ellen, with whom he’d gone to Schmall College (oh, come on). And he finds her: Olivia, half-black, half-Jewish. He adopts a dog by pulling down a sign from a telephone pole that says “I FOUND YOUR DOG.” When he brings the dog home, she begins to put on weight. After a trip to the vet, Scott learns the dog is pregnant. She later births nine pups on his and Olivia’s sofa. Scott gives Olivia a key to his apartment. The end.  Mikael Kennedy / Halpert Mikael Kennedy / Halpert 49. September 3, 2012, T. Coraghessan Boyle, “Birnam Wood”: A young couple in the seventies move from a shack to housesit a fine place on a New York lake all winter. ¶ Boyle has the reader the whole time—through the visits to potential apartments, up and down dark roads—until the end when a certain amount of energy has built up, and Keith’s woman Nora decides she’d rather be with a guy from a local bar than Keith. All this narrative energy is suddenly dissipated as Keith leaves the warm house, traverses the frozen lake in a snowstorm to window peep another youngish couple as they lie in their bed. Why doesn’t Boyle keep the story in that bedroom with Nora, Keith’s woman, and an interloper from the bar named Steve, who wants to bang her? The reader is hungry for some kind of showdown between Keith and Steve. Oh, by trudging through the wilderness to witness the other couple, Keith comes upon the idealized version of his life, the one he thought he had with Nora. Perhaps, but one still feels Boyle should have stayed in the room and figured out what happened.  Art by Jeanne Detallante Art by Jeanne Detallante 50. December 3, 2012, Antonya Nelson, “Literally”: Two boys disappear from a Houston home, and father and housekeeper set out to find them. ¶ A very thorough storyteller Nelson is, yet she omits the features that don’t matter—like whether a sixteen-year-old’s missing cell phone is recovered, the one that still has her late mother’s messages on it. Nelson creates the story of a sort of blended family in which the son of their Hispanic housekeeper becomes the “twin” of the household’s son, both eleven—the light-skinned Danny, the darker Isaac. When the boys take it upon themselves to travel an hour by bus across town to fetch Isaac’s toy Sponge Bob without permission, the action triggers a number of problems. The entire story, in a way, is a tribute to the father’s late wife, Danny’s mother, whom you only come to know by way of flashbacks, through which you discover she might have purposely put her car into the path of an eighteen-wheeler. You kind of hate Nelson for waiting until the last two paragraphs to include such pertinent information, but where else could she have possibly placed it? ¶ Because Nelson, too, claims Wichita, Kansas, as her hometown, I always look for myself in her work. In fact, in her story (in Female Trouble) “Incognito,” Nelson refers to Happiness Plaza as a meeting place for her teen-age characters. I helped build the real HP in 1968, as a manual laborer earning his next semester’s tuition. FINIS

|

AUTHOR

Richard Jespers is a writer living in Lubbock, Texas, USA. See my profile at Author Central:

http://amazon.com/author/rjespers Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

Blogroll

Websites

|