A WRITER'S WIT

Love makes your soul crawl out from its hiding place.

Zora Neale Hurston

Born January 7, 1891

My Book World

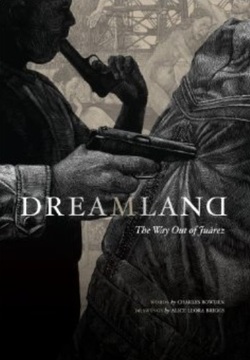

I read this book, illustrated by my friend Alice Briggs, in 2010, when it came out, but for some reason, I did not make a note of it in either my blog or my reading journals. Perhaps it is too disturbing. Perhaps I could not fully grasp what Bowden & Briggs have accomplished. Both Bowden and Briggs spent months, if not years, researching their book, exposing themselves to the same dangers that the residents of Juárez do every day. To get the story of the informant who murders a man while U.S. agents listen in and do nothing, to understand the dynamics of this and a thousand other stories, they both make themselves vulnerable to the ragged life on the border, where, because of a few political decisions made in the past, life is a constant battle between those who are selling drugs and those who would steal the contraband and/or the money it generates. It is a bloody war, one that the United States quietly participates in with its insatiable thirst for more and more illicit drugs. It is a war the U.S. ignores as well, for it is a war so deeply entrenched in the two countries’ economies, whose balance will be tipped if an “Immigration Policy” is ever brought to light. Bowden provides the illuminating prose, and Briggs the exquisite drawings that expand that which he cannot say with words.

The gist of Bowden’s entire narrative might be captured in the following passage:

“One of the early priests after the conquest of Mexico, Fray Durán, knew the old tongue and listened to the old men and wrote down their tales of what their world had been and what it had meant to them. They had been very rich and feared by other nations. They told the priest of the tribute once brought to their emperor: mantles of various designs and colors, gold, feathers, jewelry, cacao, every eighty days a million Indians trudged in bearing tribute and the list was so complete that even lice and fleas were brought and offered. The tribute collectors told the emperor, ‘O powerful lord, let not our arrival disturb your powerful heart and peaceful spirit, nor shall we be the cause of some sudden alarm that might provoke an illness for you. You well know that we are you vassals and in your presence we are nothing but rubbish and dirt.’ ¶ That was half a millennium ago and yet the rich still get tribute and the people who give them tribute feel as dirt and rubbish. ¶ For years and decades, for almost a century, people have looked at this system and sensed change or noticed hopes of change. And yet they all wait for change” (67).

“In the Florentine Codex, a record of the Indians’ ways that Cortés crushed with his new empire, it is noted that men who die in war go to the house of the sun and then they become birds or butterflies and dance from flower to flower sucking honey. In the old tongue, flower is xochitl, death is miquiztli” (80).

The Kentucky Club is a bar on Avenida Juárez in Juárez, the twin city to El Paso, Texas. Most of these seven stories reference a number of things in each one: The Kentucky Club itself, bourbon (or some other strong liquor), stout coffee, fathers who fail their sons in a variety of big ways, and mostly men who fail each other in love.

Sáenz’s style is deceptively simple, strong on declarative sentences and plenty of pages with a lot of white space because his dialog is, if not terse, then spare, lean. Most of the characters, gay men of various ages, live in Sunset Heights, a neighborhood in El Paso, but plenty of them cross the bridge between the two cities, the two countries as easily as most of them switch from Spanish to English—as if they are two forms of the same language. That’s life on the border: with its own lingo, its own culture, like many of the men in these stories, crossing easily from one life to another, but not without a price.

And one must not construe that this is a "narrow" book of gay men’s fiction, many of which made their way onto the shelves in the late eighties because gay men were hungry to read about themselves. It is not one of those books. Some of the protagonists are straight, some gay, some are bisexual. Each one is his own person, whether he is yet whole or not.

In the final story, “The Hunting Game,” the main character, a high school counselor, speaks of one of his students, who has been abused all his life by his father. Sáenz’s metaphors, like his prose, are deceptively simple:

“We grabbed a bite to eat. He ate as if he’d never tasted a burger before. God, that boy had a hunger in him. It almost hurt to watch. ‘I’ll be eighteen in three months. And I’m going away. And he’ll never be able to find me’” (209).

On the same page, Sáenz demonstrates through “dream” how the paths of these two males (one older, one very young) will cross one another by virtue of the pain both have suffered at the hands of their fathers:

“I wanted to tell him that his father would always own a piece of him, that he would have dreams of his father chasing him, dreams of a father catching him and shoving him in a car and driving him back home, dreams where he could see every angry wrinkle on his father’s face as he held up the belt like a whip. He would find out on his own. He would have to learn how to save himself from everything he’d been through. Salvation existed in his own broken heart and he’d have to find a way to get at it. It all sucked, it sucked like hell. I didn’t know what to tell him so I lied to him again. ‘He’ll just be a bad memory one day.’ He nodded I don’t think he really believed me, but he wasn’t about to call me a liar” (209).

Men in power can easily change borders on maps with the quick exchange of currency, but borders that exist in people’s hearts are much more difficult to traverse.

WEDNESDAY: LAS VEGAS PHOTO ESSAY

RSS Feed

RSS Feed