Trash Galore

My Book World

I made a number of notes (as well as using Kindle’s handy yellow highlighter), but I fear they would interest only me, so I introduce Rachel Maddow's book by way of the following passage. “‘Not since the peace-time years between World War I and World War II,’ according to a 2011 Pew Research Center study, ‘has a smaller share of Americans served in the armed forces.’ Half of the American public says it has not been even marginally affected by ten years of constant war” (202).

And yet I wonder . . . haven’t more than half of Americans been

. . . affected? Haven’t more than half of us known at least one family affected by the war, at least known of a soldier (even a friend of a friend) killed or disabled by the war? Haven’t more than half of us known at least one person whose business has folded during this decade in which the war-induced deficit (along with other controllable factors) has crushed the economy?

In addition to demonstrating how the country has drifted to a new kind of warfare—distant, affecting civilian life hardly at all, almost unreal because it’s kept out of the public eye—Maddow brings to our attention how little U.S. citizens have at stake, apparently. Because our last two wars have been fought without a draft, without civilian sacrifice (except for, needless to say, the friends and relatives of over 4,500 men and women), without the approval of the civilian population who is paying and will continue to pay for these wars—we are a population that has drifted into war and will be less and less likely to drift out of it. My grandfather, my father, my uncles, my cousin all fought in various wars with mixed results. What will be the ultimate result of our decade of war?

Maddow, despite the progressive stance she takes on her show, manages to approach her subject objectively--siting support from military experts at both ends of the political spectrum. My only criticism concerns Maddow’s prose. Her writing is both elegant and pedestrian, at turns. It is elegant when she is making a point, employing “drift” as a fine extended metaphor throughout the book, articulating herself with a vocabulary that reflects her education.

On the other hand, her prose sometimes reads as if she has dictated one of her evening presentations complete with single-word fragments, not to mention using the word “busted.” Okay, it’s fine to opt for busted in informal usage or a context pertaining to police work (The detective busted him on the spot.), but in a book in which Maddow has gone to great lengths to be accurate and eloquent, might she please avoid the word “busted?” A “busted fuel line” (230) could easily be transformed to a “broken fuel line,” a “damaged fuel line.” In another instance, “broke-down busted, overgrown, spongy stairs,” (243) seems a bit like overkill—particularly in the context of describing the home Maddow and her partner are buying. Surely any editor over the age of forty—an editor who has mastered grammar and composition—could catch these instances and elide them.

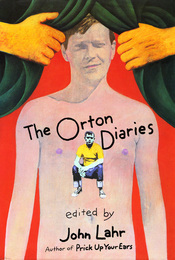

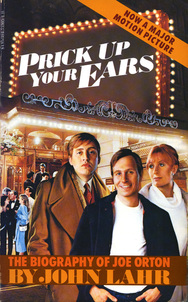

25th Anniversary of Prick Up Your eArs

Joe Orton, Playwright

Joe Orton, Playwright  Orton

Orton Orton is brutally frank concerning more substantive matters, as well. “I got to Brian Epstein’s office at 4:45. I looked through The New Yorker. How dead and professional it all is. Calculated. Not an unexpected line. Unfunny and dead. The epitaph of America” (73). Whether he’s right or wrong, he seems to state his opinion with authority.

Fifteen years earlier, Halliwell, well-educated but lonely, had taken a poor teen-aged Orton under his wing, to educate him and provide him a safe haven in which he might develop his craft. Halliwell considered himself the writer in their duo, and when Orton began to experience success that included a bigger bank account, Halliwell’s jealousy got the best of him. One can extrapolate from Orton’s journal entries that he was fed up with Halliwell and nearly ready to leave him.

Recently, I re-read both of the Orton books, twenty-five years after first devouring them. I've also seen the film version of his hit play, Entertaining Mr. Sloane. I still find his works astonishing. In them I find the courage to be the writer I would like to be: saying that which I believe is true, rather than that which will be acceptable to the public. Of course, I still succumb the latter. I would like to be read by a broad audience. Still . . . I look to his journals for the right tone, the point of view that tells the rest of the world to go f@#k themselves while creating the works I wish to create.

A Workshop For Editing the Novel

Author Carol Dawson, with at least four books to her credit, conducted the week-long course on how to revise and edit a novel. I’ve attended writing workshops before, mostly those concerning the writing of short stories. In this one, every exercise had to do with the novel manuscript I had brought to the group. At our first meeting, Ms. Dawson told an amusing tale of overhearing one of her students saying, “If you take Carol’s class, you’d better wear your big-girl panties.” Even though our group was evenly divided between men and women, no one disagreed with the idea that we were in for a tough ride.

Actually, the workshop—painful as it was at times (seems that my novel didn’t have a hook, that opening line that makes someone want to forget his or her chores and read on into the night)—was also quite helpful. Editing requires one to leave his or her creative shoes at the door. It requires one to look at his or her text as if it belongs to someone else. One must cut, cut, cut. One must chop "ly" adverbs away from speech attributions (he said hesitantly). One must cut most adjectives. One must cut material that doesn’t move the narrative along. I returned home with much to think about, and much to do. I highly recommend Dawson’s course, particularly if it’s held in Alpine.

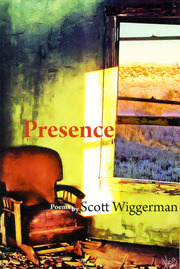

Poet Scott Wiggerman

Poet Scott Wiggerman

Whooee, what a ride.

Joe Nick Patoski

Joe Nick Patoski

RSS Feed

RSS Feed