A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

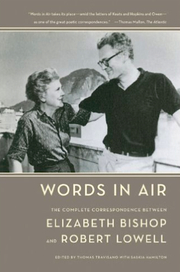

Reading the published letters exchanged between two important figures in twentieth-century American literature, among many things, has allowed me the proper venue for being a voyeur! The details Lowell and Bishop reveal about themselves, their families, and friends is astounding. The entire enterprise took me the better part of six months, not because I was a particularly slow reader or because I found the reading boring but because each time I opened the book I was only able to take in ten or twenty pages before becoming saturated. By reading nearly every footnote and making a note on every book or poem or piece of music or work of art that these two fine artists recommended or alluded to, I was slowed to the pace of enjoying a box of chocolates, a bit at a time.

Elizabeth Bishop herself cites composer Virgil Thompson: “‘one of the strange things about poets is the way they keep warm by writing to one another all over the world’” (494). Indeed, these two keep each other warm for thirty years, from 1947, when both are beginning to experience success, to 1977, when Robert Lowell dies of a heart attack in a “taxi from Kennedy Airport on his return to New York on September 12” (xli). Bishop dies on September 21 “in the early evening of a cerebral aneurysm” (xli). No one, absolutely no one, writes letters like these any longer, not even literati. Or if they do, they are not saving them in boxes. As soon as a party dies, unless he or she has made copies of their emails there shall remain no record. And do those electronic memoranda even count as letters?

I would love to share the thousands of bits of information that Lowell and Bishop leave us by way of their letters, but I shall confine my nuggets to several categories of information: Literary Criticism, Keen Observations, the Personal, and Gossip.

Nuggets:

EB: “There’s a little Catholic girl named Flannery O’Connor here now [Yaddo], who will remain if she can—a real writer, I think one of the best to be when she is a little older. Very moral (in your sense) and witty—whom I’m sure you’d like” (79).

EB: “Good lord—there’s a fifteen year old girl next door whose voice & general personality is just about as restful as a stuck automobile horn” (85).

EB: “Marianne [Moore] is wonderful, that’s all. If I don’t mention my health she writes implying that she knows I’m concealing my dying throes from her. If I say I’ve never felt better in my life (God’s truth) she writes ‘Brave Elizabeth!’ (Lota [EB’s longtime companion] says it’s a form of aggression). She used to send one rather stolid, timid friend of ours on Errands of Mercy, to people he’d never met. She told him that ‘poor Peter Monro Jack’ was in desperate straits, sick, lonely, heaven knows what all, and the friend went to call, probably taking a bag of groceries or a bunch of flowers, and found a large gay party going on, with everyone in evening dress” (189).

EB: “Ll showed me a long verse-letter, very obscene, he’d received from Dylan T[homas] before D’s last trip here [New York]—very clever, but it really can’t be published for a long, long time, he’s decided. About people D. met in the U.S. etc.—one small sample: A Streetcar Named Desire is referred to as “A truck called F———“ (215).

RL: “Psycho-therapy is rather amazing—something like stirring up the bottom of an aquarium—chunks of the past coming up at unfamiliar angles, distinct and then indistinct” (92).

RL: “I have just finished the Yeats Letters--900 & something pages—although some I’d read before. He is so Olympian always, so calm, so really unrevealing, and yet I was fascinated” (160).

RL: “Probably you forget, and anyway all that is mercifully changed and all has come right since you found Lota. But at the time everything, I guess (I don’t want to overdramatize) our relations seemed to have reached a new place. I assumed that would be just a matter of time before I proposed and I half believed that you would accept. Yet I wanted it all to have the right build-up. Well, I didn’t say anything then” (225).

EB: “so I suppose I am just a born worrier, and that when the personal worries of adolescence and the years after it have more or less disappeared I promptly have to start worrying about the decline of nations . . . But I really can’t bear much of American life these days—surely no country has ever been so filthy rich and so hideously uncomfortable at the same time” (229). 8/28/57

EB: “We actually did go through the Doldrums—a day of them. The water absolutely slick and flat and the flying fish making sprays of long scratches across it, exactly like finger-nail scratches. Aruba is a little hell-like island, very strange. It rarely if ever rains there, and there’s nothing but cactus hedges and prickly trees and goats and one broken-off miniature dead volcano. It’s set in miles of oil slicks and oil rainbows and black gouts of oil suspended in the water, crude oil—and Onassis’ tankers on all sides, flying the flags of Switzerland, Panama, and Liberia” (245).

RL: “The man next to me is [in McLean’s, a mental health facility] a Harvard Law professor. One day, he is all happiness, giving the plots of Trollope novels, distinguishing delicately between the philosophies of Holmes and Brandeis, reminiscing wittily about Frankfurter. But on another day, his depression blankets him” (252).

RL: “You must read the [Boris] Pasternak Dr. Zhivago, badly translated but dwarfing all other post-war novels except Mann. Everyone says it’s great but too lyrical to be a novel. I feel shaken and haunted by the main character” (267). “bigger perhaps than anything by Turgenev and something that alters both the old Russia and the new for us—alters our own world too.” (271).

EB: “When your letter came I was reading Dr. Jivago (Zhivago, in English)—in French. I stopped part way through because the book’s owner wanted it back, and I think I’ll finish it in English. I agree with you completely, I even liked the poems at the end, as much as one could tell about them” (274).

RL: “Fred Dupee, and James Baldwin (the colored writer) [sic] and I talked at Brandeis last week. We were each paid $200 and had limp little audiences of about thirty wriggling students. I like Baldwin’s Negro [sic] essays very much—no blarney like [Richard] Wright’s when he isn’t giving a real scene and has to generalize. I am now trying to obliterate my abolitionist pangs before seeing [Jarrell] Randall” (291).

RL: “The other night [Allen] Ginsberg, [Gregory] Corso, and [Peter] Orlovsky came to call on me. As you know, our house, as Lizzie [Hardwick] says, is nothing if not pretentious. Planned to stun people. When they came in, they all took off their wet shoes and tiptoed upstairs. They are phony in a way because they have made a lot of publicity out of very little talent. But in another way, they are pathetic and doomed . . . there was an awful lot of subdued talk about their being friends and lovers, and once Ginsberg and Orlovsky disappeared in unison to the john and reappeared on each other’s shoulders . . . I think they’ll die of TB” (297-8).

EB: “Also Ned Rorem wrote me he’d seen you in Buffalo. He’s quite a good song writer, I believe (& he thinks so, too)” (307). Meow!

EB: “That Anne Sexton I think still has a bit too much romanticism and what I think of as the “our beautiful old silver” school of female writing which is really boasting about how ‘nice’ we were. V[irginia] Woolf, K[atherine] Anne Porter, [Elizabeth] Bowen, R[ebecca] West, etc.—they are all full of it. They have to make quite sure that the reader is not going to mis-place them socially, first—and that nervousness interferes constantly with what they think they’d like to say . . . I wrote a story at Vassar that was too much admired by Miss Rose Peebles, my teacher, who was very proud of being an old-school Southern lady, and suddenly this fact about women’s writing dawned on me, and has haunted me ever since” (333).

RL: “there’s just a queer, half-apocalyptic, nuclear feeling in the air, as tho nations had died and were now anachronistic, yet in their anarchic death-throes would live on for ages troubling us, threatening the likelihood of life continuing” (381).

RL: “I was rather on tiptoe that my poems had been intrusive, and read you letter with great relief. Your suggestions on ‘Water’ might be great improvements. By the way, the mermaid wasn’t your Millay parody, but something in one of your letters, inspired by Wiscasset probably. Glad this and my tampering with ‘In the Village’ didn’t annoy you. When ‘The Scream’ is published I’ll explain, it’s just a footnote to your marvelous story” (405).

EB: “Your piece on Frost is awfully nice, Cal [RL’s nickname]. And ‘Buenos Aires’ is certainly The Latin City—I’ll have to go there, I see why you liked it so much. I like the first stanzas best. But I DON’T like the phallic monument, Cal. This has nothing to do with the preceding paragraph—it is just that I think it is unoriginal. It seems to me I’ve read so many ‘Phallic monuments’ in poetry—Spend used to use it ad nauseam, for one. Oh I know it’s the Idea, and Peron, and Power, etc.—it couldn’t be more appropriate. But I feel that you can surprise us better than that.— I hope you won’t mind my saying this— The first part has so many enlightening images, then I found ‘phallus’ too expected” (448).

RL: “The Stone Phallus was meant to be awfully raw and obvious, but maybe the poem ought to end earlier” (455).

RL: “What you say about the ‘Union dead’ poem is subtly true, must be a huge hunk of health that has survived and somehow increased through all these breakdown[s], eight or nine, I think, in about fifteen years. Pray god there’ll be no more” (559).

EB: “I seem to get to places at just the wrong time—before that I spent four days at the University of Oklahoma. That was really fun; I had a wonderful time—but the desolation of that scenery, at that time of year, is incredible.— I’ve seen ‘lonely New England farmhouses’—but nothing can compare to a lonely, small-sized, ranch-house in Oklahoma. One can see for miles—all pale tan—only the pumping oil-wells lend animation to the scene—even the ‘Wild Life Reservation’—pumping away like lost lunatics—” (741).

RL: “I see us still when we first met, both at Randall’s and then for a couple of years later. I see you as rather tall, long brown-haired, shy but full of des[cription] and anecdote as now. I was brown haired and thirty I guess and I don’t know what. I was largely invisible to myself, and nothing I knew how to look at. But the fact is we were swimming in our young age, with the water coming down on us, and we were gulping. I can’t go on. It is better now only there’s a steel cord stretch[ed] tense at about arms-length above us, and what we look forward to must be accompanied by our less grace and strength. Well, no more dies irae; I wonder if Christians believing in immortality saw their lives as less circular” (776).

EB: “However, Cal dear, maybe your memory is failing!— Never, never was I ‘tall’—as you wrote remembering me. I was always 5 ft 4 and ¼ inches—now shrunk to 5 ft 4 inches— The only time I’ve ever felt all was in Brazil. And I never had ‘long brown hair’ either!” (778).

RL: “I still thrill to your visit. After a little, it seemed as if almost thirty years had rolled back, and we were talking, brownhaired, callow and new in New York, Washington or Maine. Voice and image seemed much more what we were than what we are—or is the essence as it was?” (793).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed