A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

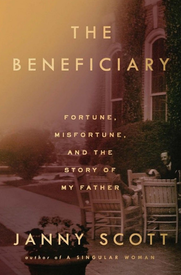

Journalist Janny Scott limns a harrowing portrait of her father, Robert Montgomery Scott, yet his story does not begin that way. Between the dedication and epigraph pages of the book appears a family tree extending back three generations. From a vast variety of sources, Scott brings to light the larger-than-life characters who are her ancestors, one set of grandparents and two sets of great-grandparents. Most persons would not necessarily know that much about their people, but for generations this family live off the good fortune and largesse of Thomas A. Scott, a railroad baron of the nineteenth century. They live on one property, Ardrossan, larger than New York’s Central Park, west of Philadelphia. Scott’s grandmother, flamboyant Helen Hope Montgomery, is the real-life personage upon which Katherine Hepburn’s character is based in the 1940 film, The Philadelphia Story. There is so much spectacle in this family, people who can, and do, almost anything they wish to do, that we almost lose sight of the subject of the book, Janny Scott’s father.

At one point, when journalist Scott is young and becomes interested in writing, her father promises her possession of his journals one day. Through the years the promise is lost, both because she puts the idea on a back burner and because her father is apparently reluctant to hand them over. Following his death, from a long bout with alcoholism, Janny Scott unearths them in one of those hiding-in-plain-sight locations, where all she must do is recall the four-digit default household code to unlatch his trunk, and voila, there they are: decades of notebooks full of loose-leaf pages. Scott magically (it’s really arduous work, one must realize) gathers all of her sources, including this gold mine, and produces a portrait of her father, the beneficiary of generations of great fortune. Only, the portrayal of a human life is never that simple. The rich—we often don’t have much sympathy for them—have a uniquely difficult time in life. They often wield too much power for their own good, and Scott herself says it best:

“The diaries, I began to think, were an inheritance of sorts—unanticipated, undeserved, a stroke of fortune. But, like an inheritance, they came at a cost. Land, houses, money: Wealth had tumbled in my father’s family from one generation to the next. Each new descendant arrived as an unwitting conduit for its transmission. You had a right to enjoy it, an obligation to protect it, a duty to pass it on to your own unsuspecting children. It was a stroke of good fortune, of course. But what you could never know, starting out, was how those things would influence decisions you’d make over a lifetime” (220)

NEXT TIME: My Journey of States-47 North Dakota

RSS Feed

RSS Feed