A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

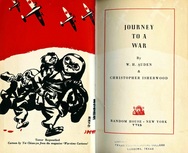

I'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late Anglo-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the eleventh in a series of twenty.

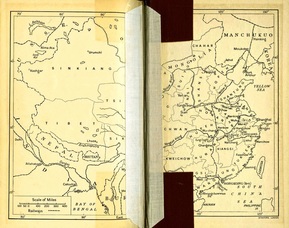

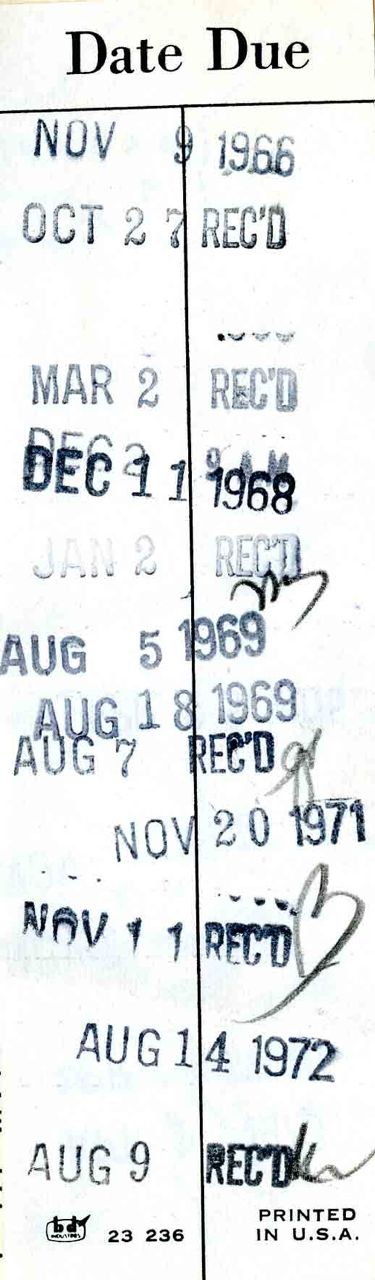

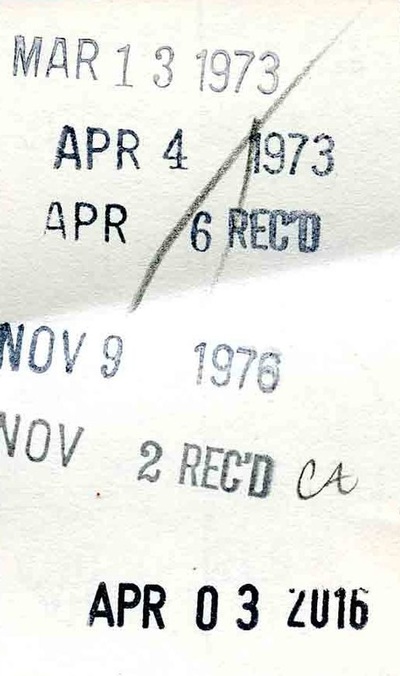

Books have a strange life of their own. In checking the date due slip of this tome accessioned to the Texas Tech University Library, I see that it is checked out in November, 1966, the autumn I go away to college, then in 1968, when I’m a junior, 1969 a senior. 1971, 1972, 1973. And last, 1976. This book about Isherwood and Auden’s joint trip to China in 1938—brown and worn with its spine heavily taped—sits on the shelf for forty years, until I pick it up, as part of my marathon to read all twenty works of Isherwood. Odd. I literally blow dust off its top and begin to read.

The book closes with two sections, In Time of War, a Sonnet Sequence of twenty-seven poems and thirteen pages of “commentary” in the form of verse—courtesy of W. H. Auden.

Some nuggets from the book:

“That is what War is, I thought: two ships pass each other, and nobody waves his hand” (29).

“During the past fortnight, eleven Japanese had been brought down. The Government had offered a reward to anybody who could bring down a plane; as a result, anti-aircraft defence had become a local sport, like duck-shooting. When the planes came over, everybody blazed away—even the farmers with their blunderbusses in the fields” (37). Isherwood peppers his prose with “Japs,” an acceptable appellation in those days.

“Most of the Germans have been in China for several years. They belong to the pre-Hitler emigration period, when an ambitious officer could foresee no adventurous military career in his own country, and often preferred to be abroad” (57). Isherwood speaks fluent German, and he sometimes has interesting interchanges with the Germans.

“As we walked home the whole weight of the news from Austria descended upon us, crushing out everything else. By this evening a European war may have broken out. And here we are, eight thousand miles away. Shall we change our plans? Shall we go back? What does China matter to us in comparison with this? Bad news of this sort has a curious psychological effect: all the guns and bombs of the Japanese seem suddenly as harmless as gnats. If we are killed on the Yellow River front our deaths will be as provincial and meaningless as a motor-bus accident in Burton-on-Trent” (59). The two men are conflicted about their past involvement—in their twenties—with Germany and Austria.

“China, says Dr. MacFadyen, is a terrible place for growths and tumours. In the hospital he has a whole museum of bladder-stones. One of his patents had a polypus [polyp] growing out of his nose, so long that you could wind the pedicle round his neck” (103-4). From this passage one realizes just how backward, how terribly poor 1930s China is.

Isherwood manages to capture the ironies of war, a pretty dog with no moral sensibilities: “Meanwhile there was time for a stroll round the village. It was a glorious, cool spring morning. On a waste plot of land beyond the houses a dog was gnawing what was, only too obviously, a human arm. A spy, they told us, had been buried there after execution a day or two ago; the dog had dug the corpse half out of the earth. It was rather a pretty dog with a fine, bushy tail. I remembered how we had patted it when it came begging for scraps of our supper the evening before” (112).

Here, he comments on the hale attitude with which the Chinese approach war: “The average Chinese soldier speaks of China’s chances with an air of gentle deprecation, yet he is ultimately confident or, at least, hopeful. ‘The Japanese,’ said one of them, ‘fight with their tanks and planes. We Chinese fight with our spirit.’ The ‘spirit’ is certainly important when one considers the Chinese inferiority in armaments (today’s new guns were a remarkable exception) and their hopeless deficiency in medical services. European troops may appear more self-confident, more combative, more efficient and energetic, but if they had to wage this war under similar conditions they would probably all mutiny within a fortnight” (117).

Here Isherwood comments on the amenities of a particular inn: “The Guest-House at Sian must be one of the strangest hotels in the world. A caprice of Chang Hsueh-liang created it—a Germanic, severely modern building, complete with private bathrooms, running water, central heating, and barber’s shop; the white dining-room has a dance-floor in the middle, and an indirectly rose-lit dome. Sitting in the entrance-lounge, on comfortable settees, you watch the guests going in and out. With the self-assured briskness of people accustomed to luxury and prompt service, inhabitants of a great metropolis. Those swing-doors might open on to Fifth Avenue, Piccadilly, Unter den Linden. The illusion is nearly complete” (129).

The following is an interesting anecdote that a Dr. Mooser passes onto Isherwood: “While he was working in Mexico he was summoned to the bedside of an Englishman named David H. Lawrence, ‘a queer-looking fellow with a red beard.’ I told him: ‘I thought you were Jesus Christ.’ And he laughed. There was a big German woman sitting beside him. She was his wife. I asked him what his profession was. He said he was a writer. ‘Are you a famous writer?’ I asked him. ‘Oh no,’ he said. ‘Not so famous.’ His wife didn’t like that. ‘Didn’t you really know my husband was a writer?’ she said to me. ‘No,’ I said. ‘Never heard of him.’ And Lawrence said: ‘Don’t be silly, Frieda. How should he know I was a writer? I didn’t know he was a doctor, either, till he told me.’

Dr. Mooser then examined Lawrence and told him that he was suffering from tuberculosis—not from malaria, as the Mexican doctor had assured him. Lawrence took it very quietly. He only asked how long Mooser thought he would live. ‘Two years,’ said Mooser. ‘If you’re careful.’ This was in 1928” (138). [Lawrence dies in 1930.]

In Hangkow, near their journey’s end, Isherwood comments about one of the hotels: “Running out to meet us came a drilled troop of houseboys in khaki shorts and white shirts, prettily embroidered with the scarlet characters of their names. Mr. Charleton’s boys were famous, it appeared, in this part of China. He trained them for three years—as servants, gardeners, carpenters, or painters—and then placed them, often in excellent jobs, with consular officials, or foreign business men. The boys had all learnt a little English. The could say: ‘Good morning, sir,’ when you met them, and commanded a whole repertoire of sentences about tea, breakfast, the time you wanted to be called, the laundry, and the price of drinks. When a new boy arrived one of the third-year boys was appointed as his guardian. The first year, the boy was paid nothing; the second year, four dollars a month, the third year, ten. If a boy was stupid but willing he was taken on to the kitchen staff, and given a different uniform—black shirt and shorts. All tips were divided and the profits of the business shared out at the end of the year” (178).

And of course, the two writers cannot end the book without commenting on war, an abstraction transmogrified into the concrete: “But war, as Auden said later, is not like that. War is bombing an already disused arsenal, missing it, and killing a few old women. War is lying in a stable with a gangrenous leg. War is drinking hot water in a barn and worrying about one’s wife. War is a handful of lost and terrified men in the mountains, shooting at something moving in the undergrowth. War is waiting for days with nothing to do; shouting down a dead telephone; going without sleep, or sex, or a wash. War is untidy, inefficient, obscure, and largely a matter of chance” (202). And what has changed?

More of the same: “Mr. Wang was the civil governor of six counties, and he had prepared an exhaustive report on the atrocities of the Japanese against the civilian population. In Mr. Wang’s area eighty per cent of the houses had been burnt. Out of 1,100 houses in Siaofeng only 200 remained. Out of 2,800 in Tsinan only 3. Three thousand civilians had been killed during the past four months. Children were being kidnapped by the Japanese and sent to Shanghai—for forced labour or the brothels. Out of 110,000 refugees only ten per cent had been able to leave the district. The rest were returning, where possible, to their ruined homes, with money from the Government to buy seeds for the spring sowing. If they belonged to areas occupied by the Japanese they would be given work—either in repairing the roads or in their own handicrafts” (213).

Isherwood makes clear how conflicted he is about being conveyed by coolies in carts over muddy terrain: “The coolies strode along, relieving each other with trained adroitness. We gazed at their bulging calves and straining thighs, and rehearsed every dishonest excuse for allowing ourselves to be carried by human beings: they are used to it, it’s giving them employment, they don’t feel. Oh no, they don’t feel—but the lump on the back of that man’s neck wasn’t raised by drinking champagne, and his sweat remarkably resembles my own. Never mind, my feet hurt. I’m paying him, aren’t I? Three times as much, in fact, as he’d get from a Chinese. Sentimentality helps no one. Why don’t you walk? I can’t, I tell you. You bloody well would if you’d got no cash. But I have got cash. Oh, dear. I’m so heavy . . . . Our coolies, unaware of these qualms, seemed to bear us no ill-will, however. At the road-side halts they even brought us cups of tea” (226).

Isherwood’s utter amazement at the Chinese concept of thrift: “We stopped to get petrol near a restaurant where they were cooking bamboo in all its forms—including the strips used for making chairs. That, I thought, is so typical of this country. Nothing is specifically either eatable or uneatable. You could begin munching a hat, or bite a mouthful out of a wall; equally, you could build a hut with the food provided at lunch. Everything is everything” (231). Everything is everything.

From Sonnet XIX:

But in the evening the oppression lifted;

The peaks came into focus; it had rained:

Across the lawns and cultured flowers drifted

The conversation of the highly trained.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed