A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

I'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the twelfth in a series of twenty.

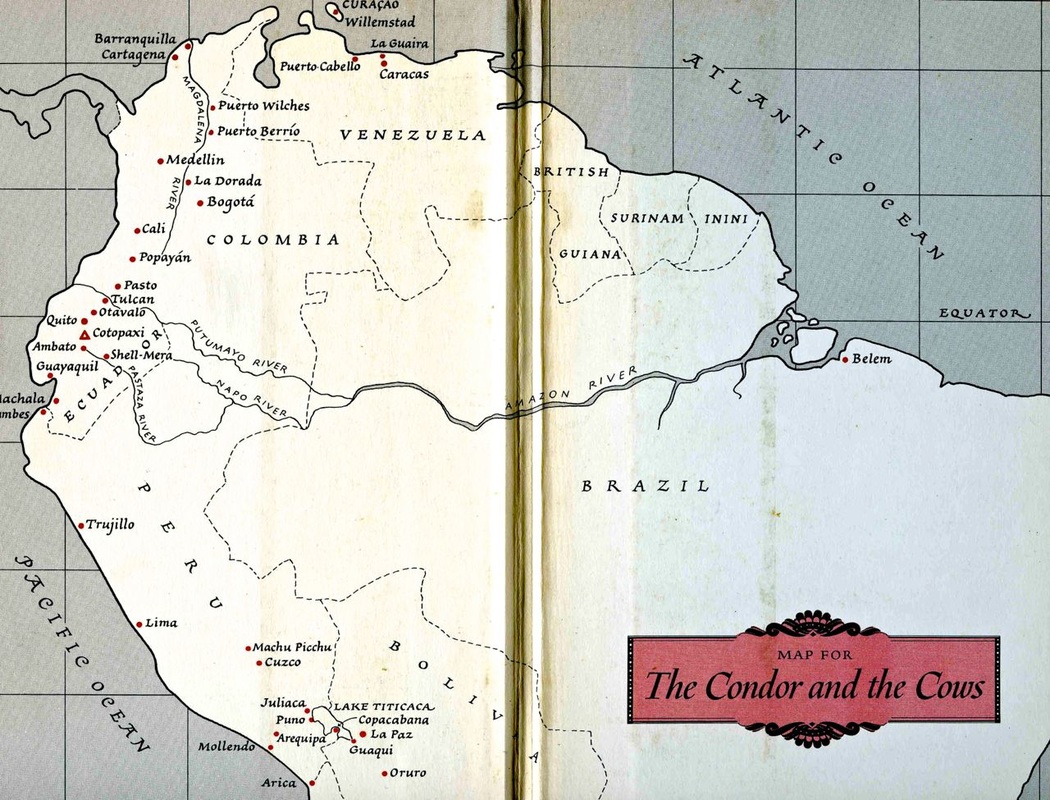

Writers don’t do this much anymore: take long journeys to foreign countries like those found in South America and pen a single book about it, but that’s what Isherwood does in The Condor and the Cows. He writes about his trip taken with lover-at-the-time and photographer, William Caskey, one that spans six months in 1947-48.

“The meaning of the title should be evident, but perhaps I had better explain that the Condor is the emblem of the Andes and their mountain republics, while the Cows represent the great cattle-bearing plains, and, more specifically, Argentina—no offense intended” (3).

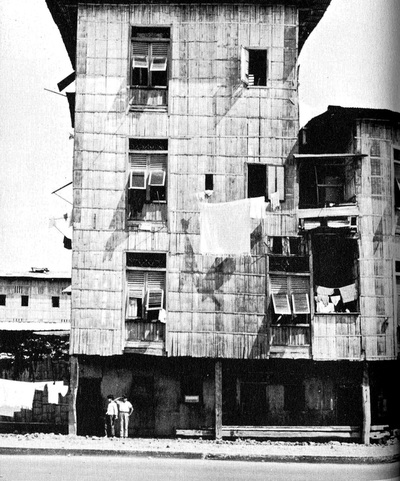

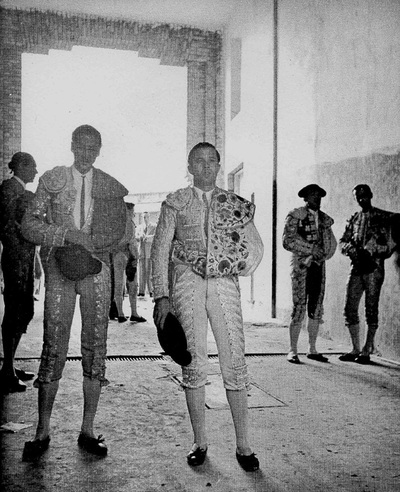

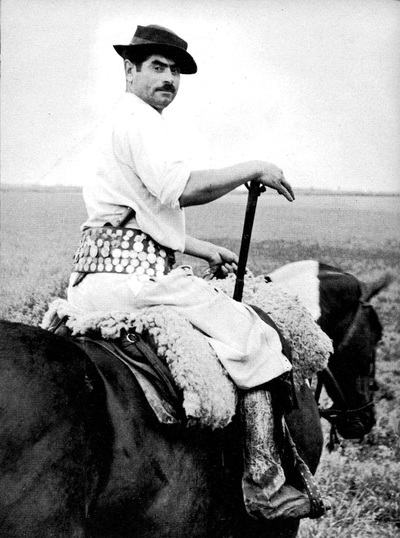

From Left to Right: Bamboo Tenement in Guayaquil | Paco Lara Entering Bullring, Bogotá | Guambia Indians | Country Girl, Pisac | A Gaucho, Argentina (All Photos by William Caskey)

“We stopped at El Banco just after dark . . . [o]n the narrow gangplank the two streams of human beings collided, surged and mingled; a yelling mob of white-cotton clothes and dark bodies—yellow, red, velvet black and plum purple, with an occasional, strangely arresting blond head. Above the confusion the ship’s band played its lively clattering music, and through the open doors of the church on the hill there was a glimpse of a priest at the altar, a remote quiet candle-lit figure, saying vespers” (34-5). A lovely description despite Isherwood’s slightly racist point of view.

We witness that POV here again as he describes Guambian Indians: “The men have short glossy black hair, shocked up into an untidy tuft, and lively impudent black eyes. Some look strikingly Mongolian. Their mouths are a bit apelike. They smile readily and don’t in the least mind if you examine their ornaments or their clothes” (67). Isherwood’s descriptions are not as insulting as perhaps his patronizing and paternalistic tone. Perhaps we can forgive him if, for no other reason, we remember he is a product of the imperialistic British Empire, born in 1904.

When caught in a certain badlands between Ecuador and Columbia, a town called Pasto, the author remarks: “We were put down at the Hotel Granada, a shabby wooden building with inside balconies around a central dining room. The bedrooms are like stables. Windowless, with great barn-doors closed by padlocks. The combined shower and toilet—the only one on the ground floor—is unfit for pigs. While we were eating a tepid greasy supper, in strolled the mail-car driver with his girl. On seeing us, he smiled without surprise but didn’t offer a word of explanation or excuse [earlier they’ve had an altercation]. We neither washed nor shaved, brushed our teeth in bottled mineral water, and went sadly and shiveringly to bed at eight-thirty” (75).

Here the author compensates for his grumpy-tourist temperament with the following account: “And at this very moment, like a miracle, the rail-bus appeared. We waved our arms frantically, hardly daring to hope that it would stop. It did stop. We scrambled thankfully on board.

That is the irony of travel. You spend your boyhood dreaming of a magic, impossibly distant day when you will cross the Equator, when your eyes will behold Quito. And then, in the slow prosaic process of life, that day undramatically dawns—and finds you sleepy, hungry and dull. The Equator is just another valley; you aren’t sure which and you don’t much care. Quito is just another railroad station, with fuss about baggage and taxis and tips. And the only comforting reality, amidst all this picturesque noisy strangeness, is to find a clean pension run by Czech refugees and sit down in a cozy Central European parlor to a lunch of well-cooked Wiener Schnitzel” (80).

Isherwood now echoes his title with this anecdote: “Mr. Cooper used also to keep a boa-constrictor and two condors. But the boa had to be gotten rid of; it was always trying to get at the other animals, or escaping and terrifying the neighbors. The condors flew away, which is a great pity; perched on the roof, they must have given the house the air of a Charles Addams drawing in the New Yorker.

“He describes how a party of his friends were riding along a narrow trail in the high mountains when they saw three condors and fired at them. The condors disappeared—to get help, apparently—for they returned a few minutes later with twenty-five others, and all of them swooped down upon the pack-train. In the confusion, two horses fell over the precipice; their riders jumped clear just in time. Condors will peck the eyes out of cows and then drive them with their wings off the edge of a cliff; the cows get killed and the condors eat them” (125).

Very subtly Isherwood tells what he believes has happened to the indigenous Indians when attacked by the Conquistadors long ago. “These people, like the Chinese peasants [referring to another trip, made in 1938 with W. H. Auden, detailed in Journey to a War], have an uncanny air of belonging to their landscape—of being, in the profoundest sense, its inhabitants. It would hardly surprise you to see them emerging from or disappearing into the bowels of the earth” (143).

It is not beneath Isherwood’s dignity to criticize others: “Cuzco is right on the trans-Andean tourist trail. This hotel is full of tourists. The majority are North American—middle-aged women schoolteachers, mostly. Grimly devout, complaining but undaunted, they make their way over the mountains from Lima to Buenos Aires—gasping in the high altitudes, vomiting and terrified in planes, rattled like dice in buses, dragged out of bed before dawn to race along precipice roads, poisoned with strange foods, tricked by shopkeepers, appalled by toilets” (145). This is an interesting comment, especially in light of the fact that he seems to echoing some of his own prissy complaints listed above.

In Buenos Aires, Isherwood makes arrangements to stay with an acquaintance from his Berlin days of the 1930s: Berthold. The author tells a long story, which I will not cite in full, in which Berthold tells of visiting New York City and running into someone he had known previously, someone whom he’d buried in Africa, thinking the man was dead! What a second-hand tale this makes. (186-8).

“Argentina, like the United States, has practically liquidated its Indian problem. And much the same manner” (193). In the same breath that he is criticizing the US for wholesale liquidation, Isherwood is betraying his own racist bent with the words “Indian problem,” as if the subjects are unwanted vermin that must be disposed of. It is perhaps a warning to all of us in this era: our words of judgment could, in future years, wind up similarly betraying us.

Introduction to My Long-Playing Records

"My Long-Playing Records" — The Story

"A Certain Kind of Mischief"

"Ghost Riders"

"The Best Mud"

"Handy to Some"

"Blight"

"A Gambler's Debt"

"Tales of the Millerettes"

"Men at Sea"

"Basketball Is Not a Drug"

"Engineer"

"Snarked"

"Killing Lorenzo"

"The Age I Am Now"

"Bathed in Pink"

Listen to My Long-Playing Records Podcasts:

"A Certain Kind of Mischief"

"The Best Mud"

"Handy to Some"

"Tales of the Millerettes"

"Men at Sea"

"My Long-Playing Records"

"Basketball Is Not a Drug"

"Snarked"

"Killing Lorenzo"

"Bathed in Pink"

Also available on iTunes.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed