A WRITER'S WIT

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a heav'n of hell, a hell of

heav'n.

John Milton

Born December 9, 1608

My Book World

I’ve been drawn to writers’ notebooks, journals, and letters for a long time, having read documents of John Cheever, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, and others. William’s notebooks are multifaceted. He makes clear that he is writing for himself; many entries have the same dreary tone that an ordinary person might use to write in a journal: physical complaints, gossip [“Gielgud too difficult to work with, somehow antipathetic” (485)], critiques of other people’s work [“Helen Hayes has flashes of great virtuosity but her performance lacks the heart and grace and poetry of Laurette’s and sometimes it becomes downright banal” (485)]. But you can categorize many threads found throughout Williams’s notebooks.

Daily complaints: his health (he must spell the word “Diarrhoea” scores if not hundreds of times), and while he does have a number of documented health problems, most of them are self-inflicted by way of extreme alcohol, tobacco, and drug use, which he freely admits to, enumerating the number of seconals he would take in a day, along with how many scotches.

Sex: if not narrative accounts of his numerous sexual pursuits with individual men, Williams gives at least a mention of said person and how long the affair did or did not last. He would remain lovers with a man named Frank Merlo, until the latter’s death, even though they were often separated and conducted a rather “open marriage,” long before the 1970s term was ever coined.

Things about which he had no compunction: stealing books from the University of Iowa and New Orleans libraries; being jailed along with a male companion as suspicious characters and not having his draft card with him.

His ideas on cruising: “Evening is the normal adult’s time for home—the family. For us it is the time to search for something to satisfy that empty space that home fills in the normal adult’s life” (281).

His opinions on writing: “A sombre play has to be very spare and angular. When you fill it out it seems blotchy, pestilential. You must keep the lines sharp and clean—tragedy is austere. You get the effect with fewer lines than you are inclined to use” (305).

On loneliness: “This evening a stranger picked me up. A common and seedy-looking young Jew with a thick accent. I was absurdly happy. For the first time since my arrival here [in Florida] I had a companion” (325).

Personal philosophy: “One lives a vast number of days but life seems short because the days repeat themselves so. Take that period from my 21 – 24 yr. when I was in the shoe business, a clerk typist in St. Louis at $65 a month. It all seems like one day in my life. It was all one day over and over” (349).

Success: Williams is clear in a number of places about how the purity of his writing life is upended by success (Glass Menagerie in 1944):

“The trouble is that I am being bullied and intimidated by my own success and the fame that surrounds it and what people expect of me and their demands on me. They are forcing me out of my natural position as an artist so that I am in peril of ceasing to be an artist at all. When that happens I will be nothing because I cannot be a professional writer” (493).

“I have been twisted by a world of false values—And the talent died in me from over-exposure, a sort of sun stroke under the baleful sun of ‘success’—naturally I will go on trying to live as well as I can and the probability is that tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow, I will begin to edge back into the state of illusion. And hope” (515).

“The tragedy [suicide of Tom Heggen, writer of Mr. Roberts] points up once more the crying need for a different sort of theatre in America, one that will be a cushion to both fame and fortune which will provide the young artist with a continual, constructive contact with his profession and a continual chance to function in it. Otherwise these losses will be repeated then, and there is no field of creative work in which they can be less afforded” (503).

“I want to shut a door on all that dreary buy and sell side of writing and work purely again for myself alone. I am sick of being peddled. Perhaps if I could have escaped being peddled I might have become a major artist. It’s no one’s fault. It’s just a dirty circumstance, and now’s maybe too late to correct it” (635).

Books Williams read that I believe I must now put on my list: Yukio Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask. The Denton Welsh Journals, edited by Jocelyn Brooke. Denton Welch’s Maiden Voyage, In Youth Is Pleasure, A Voice Through a Cloud, Brave and Cruel, and A Last Sheaf. Jean Cocteau’s Le Livre Blanc. Donald Windham’s The Dog Star, The Hero Continues, Two People, The Warm Country, and Emblems of Conduct.

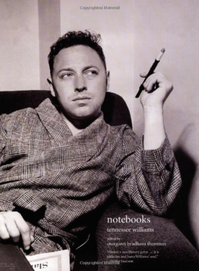

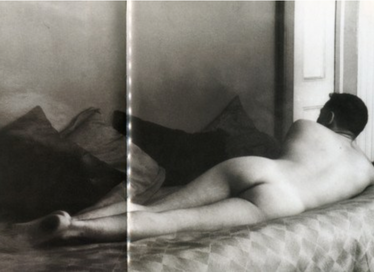

Countless interesting or titillating photographs of Williams (and some of his paramours) when he was young:

So much of Williams’s life seems to be self destructive. Not until 1957, at the age of forty-six does he consider beginning psychoanalysis. “The moment has certainly come for psychiatric help, but will I take it?” (701).

To anyone who wishes to understand Tennessee Williams and his work, you must realize your work is probably not complete until you read this tome, including the 1,090 footnotes (most of which I did plow through because they are substantive and interesting in their own right).

NEXT TIME: Behind the Book, "Handy to Some"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed