A WRITER'S WIT |

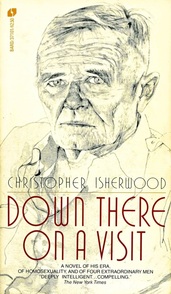

I'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the fifteenth in a series of twenty-four.

My Book World

I first read this novel in 1980 on my way back from a trip to Europe. I marked very little, and, frankly, I don’t think I understood much of what Isherwood was talking about. I hadn’t yet studied literature in depth. I hadn’t studied Buddhism or the act of meditation. It meant little to me. This reading seemed richer, especially in light of the fact that I’ve read almost all the author’s works including his thousand-page Diaries, Volume One, 1939-60.

One of the main characters of Isherwood’s novel, Paul, scoffs at the character named Christopher Isherwood by saying: “You know, you really are a tourist, to your bones. I bet you’re always sending postcards with ‘Down here on a visit’ on them. That’s the story of your life . . . . (308). So, in effect, the novel is a threading together of four visits down there.

“Mr. Lancaster” begins in London, in 1928, when the character Isherwood is twenty-three and takes a voyage to northern Germany by way of a tramp steamer called the Coriolanus. He does this courtesy of one Mr. Lancaster, who becomes both like a father and a son to Isherwood. Lancaster dies at his own hands, it is conjectured, because of his impotence. And another character, Waldemar, makes his first appearance in the book, this section, which seems more like a short story than a novel segment.

The second part of the novel is “Ambrose,” a former mate of Isherwood’s at Cambridge (one supposes W. H. Auden is the model), who buys property on a Greek island, St. Gregory, and is in the process of building a house in this 1930 segment. He invites Isherwood and his Berliner companion, Waldemar, to venture down to visit. The only other inhabitants of the island are some scamps who, though working as laborers on the new house, also get into a lot of mischief as they head to the mainland each night. The island is rife with snakes, flies, and a host of other problems that probably only young men could tolerate. Yet the place is not without its charms:

“When we have eaten supper, we sit out in front of the huts, at the kitchen table, around the lamp, unhurriedly getting drunk. As soon as the lamp has been placed on the table, this becomes the center of the world. There is no one else, you feel, anywhere. Overhead, right across the sky, the Milky Way is like a cloud of firelit steam. After the short, furious sunset breeze, it gets so still that the night doesn’t seem external; it’s more like being in a huge room without a ceiling” (85).

The “Waldemar” section of the novel is set in 1938 and begins on another boat, this time outside the Dover Harbour. Isherwood, the man, the author, has just returned from his 1938 trip to China with Auden. In this section, Auden is again the model for a different character, Hugh Weston. As character Isherwood and companion Dorothy step off the boat, whom should they run into but Waldemar! There would be no such thing called a novel without the idea of coincidence. Isherwood is terribly concerned with the concept of class and is horrified when on a visit to his family, they treat Waldemar as a low-class ragamuffin, instead of their son’s dear friend. Christopher is also very concerned with the lead-up to war in Germany. Waldemar begs Christoph to take him with him to the US, but Christopher says it is impossible. Yet Waldemar reappears once again!

In “Paul,” the fourth and final part of his novel, Isherwood moves to Los Angeles, the time 1940. He connects with a male prostitute, a gorgeous, highly paid young man who is really difficult to get to know, but Christopher tries. This section reflects Isherwood’s attempts to achieve a spiritual life by way of Buddhism. He makes an acquaintance with a swami, Augustus Parr, and, when Paul indicates that he would like to become more spiritual, the two connect, spend almost an entire day together. This section wears thin before the end, in which Paul, winds up returning to Europe and dying essentially of drug usage. Isherwood, the author, does a little too much deus ex machina to make things turn out easily for him, instead of allowing the story to end with a bit more conflict or complexity.

I think Down There on a Visit is in actually a collection of long stories more than it is a novel. Just because you refer to a character that appears earlier does not make it a novel. Even if Waldemar keeps reappearing in all four parts, one cannot necessarily call this work a novel. A novel is one large sweep of motion, with one climax. This one has four for each part, and then the author has, with great skill threaded the four of them together. I’m not criticizing the execution, exactly. I’m just saying it should have been sold as linked stories (though such a thing had not yet been marketed by the publishers at that time) or four novellas, but not as a novel. That said, one cannot praise Isherwood enough for his sense of lyricism and competence with the English language. They are always superb.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed