A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

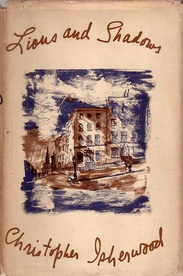

I'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the seventh in a series of twenty.

As I examine this copy borrowed from the Texas Tech University main library (1.7 million volumes), I note that it is accessioned in 1964. By examining the date due slip, I can see I’m only the third person to check out this book since 1972—making me a rare cat indeed. In remarks at the beginning, Isherwood says that his book “is not, in the ordinary journalistic sense of the word, an autobiography; it contains no ‘revelations’; it is never ‘indiscreet’; it is not even entirely ‘true’” (7). He goes on to state that the book is a record of a man, him, in his twenties, as he forges ahead in his life as a young novelist.

This young artist makes a short trip to France. He attends university in England. “I had not been in Cambridge a fortnight before I began to feel with alarm that I was badly out of my depth. The truth, as I now discovered for the first time, was that I was a hopelessly inefficient lecturee. I couldn’t attend, couldn’t concentrate, couldn’t take proper notes” (62).

He records the meaning that relationships there give him, including Mr. Holmes, a benefactor of sorts. “Isherwood the artist was an austere ascetic, cut off from the outside world, in voluntary exile, a recluse” (97).

Isherwood co-writes narratives with a close friend. One book in particular, a “Hynd and Starn” story, would be accompanied with fireworks, gramophone, and dialogue would be spoken. Copies would be free. “Our friends would find, attached to the last page, a pocket containing banknotes and jewels; our enemies, on reaching the end of the book, would be shot dead by a revolver concealed in the binding” (114). Isherwood simply doesn’t live long enough; today’s technology might have afforded him at least a few of these book innovations!

At the end of his second year Isherwood deliberately fails his exams by giving nonsensical answers. At the time, because the professors and administration act as if he has simply chosen to leave Cambridge, no one knows what he has done. Failure is painful, but he believes he is right to strike out on his own. “Suppose I stayed on and did, somehow, get a degree: what would become of me? I should have to be a schoolmaster. But I didn’t want to be a schoolmaster—I wanted, at last, to escape from that world. I want to learn to direct films . . . [h]ow I longed to be independent, to earn money of my own! And I had got to wait another whole year!” (125).

After leaving Cambridge, Isherwood takes a series of positions, one as a personal secretary, another as an English tutor for young pupils. During this time he also teaches himself how to write. A dear friend, also a writer, “Chalmers,” asserts his theories, and Isherwood concurs: “‘I saw it all suddenly while I was reading Howards End . . . Forster’s the only one who understands what the modern novel ought to be . . . Our frightful mistake was that we believed in tragedy: the point is, tragedy’s quite impossible nowadays . . . We ought to aim at being essentially comic writers . . . The whole of Forster’s technique is based on the tea-table: instead of trying to screw all his scenes up to the highest possible pitch, he tones them down until they sound like mothers’-meeting gossip . . . In fact, there’s actually less emphasis laid on the big scenes than on the unimportant ones: that’s what’s so utterly terrific. It’s the completely new kind of accentuation—like a person talking a different language’” (173-4).

The author chronicles his early experiences: “. . . I had sent the manuscript, already, to two well-known publishers. They had refused it, of course. One of them wrote saying that my work had ‘a certain literary delicacy, but lacked sufficient punch’—a pretty damning verdict, when your story ends with a murder” (205).

He indirectly addresses the idea of being gay, as well as the issue of being an artist, critical of society: “Does anybody ever feel sincerely pleased at the prospect of remaining in permanent opposition, a social misfit, for the rest of his life? I knew, at any rate, that I myself didn’t. I wanted—however much I might try to persuade myself, in moments of arrogance, to the contrary—to find some place, no matter how humble, in the scheme of society. Until I do that, I told myself, my writing will never be any good; no amount of talent or technique will redeem it: it will remain a greenhouse product; something, at best, for the connoisseur and the clique” (247-8).

Isherwood writes of the Great War: “I came to regard Lester as a ghost—the ghost of the War. Walking beside him, at midnight, on the downs, I asked him the question which ghosts are always asked by the living: ‘What shall I do with my life?’ ‘I think,’ said Lester, ‘that you’d make a very good doctor.’ He had already tried that at Cambridge and failed!

Most of all Isherwood continues to modify his craft: “Therefore epics, I reasoned, should start in the middle and go backwards, then forwards again—so that the reader comes upon the dullness half-way through, when he is more interested in the characters; the fish holds its tail in its mouth, and time is circular, which sounds Einstein-ish and brilliantly modern” (297).

Early on, “a lady novelist who was an old friend of our family,” reads his manuscript and in part tells him: “‘If you really have talent, you know, you’ll go on writing—whatever people say to you’” (119).

Isherwood takes her advice and—twenty books later—never looks back, except, of course, to write about it!

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed