A WRITER'S WIT

Two can live as cheaply as one—if they both have good jobs.

Sigmund Freud

Born May 6, 1856

My Book World

The author, born in Shanghai, China, in 1930, explains in the Foreword that this novel is based on his experiences during World War Two, during which he was interned from 1942 to 1945, in his early teens. Indeed, the main character Jim is separated from his parents. The 1987 film by Steven Spielberg makes a big to-do of their separation, but in the book it seems to happen as it might happen to a child. One moment his parents are present, as he is knocked down in a certain melee. The next moment his mother is gone: “Jim’s mother had disappeared, cut off from him by the column of military trucks” (32). Then his father lies down with him, but mysteriously, the next day Jim finds himself alone in a hospital, hoping his parents will come for him soon.

This bright boy must now negotiate the muddy and treacherous waters of wartime virtually on his own. I was inspired by a recent viewing of the film to read the book. I recall many of the movie’s scenes as they unfold on the pages. However, Spielberg takes some liberties, as film directors are wont to do, in order to tell his story. The novel is multi-layered, with countless poignant and sad scenes, but Spielberg turns it into a boy’s adventure story. Both are great, but they are not equally great works.

In the beginning, the eleven-year-old Jim, intelligent though he is, possesses childish and feckless notions:

“He thought of telling Mr. Maxted that not only had he left the cubs and become an atheist, but he might become a Communist as well. The Communists had an intriguing ability to unsettle everyone, a talent Jim greatly respected” (15).

“Jim had little idea of his own future—life in Shanghai was lived wholly within an intense present—but he imagined himself growing up to be like Mr. Maxted” (16).

“In many ways the skeletons were more live than the peasant farmers who had briefly tenanted their bones. Jim felt his cheeks and jaw, trying to imagine his own skeleton in the sun, lying here in this peaceful field within sight of the deserted aerodrome” (17).

The novel, like a children’s story, moves from one episode to the next, one scene to the next. I found it hard to follow at first. But then I realized that perhaps Ballard wishes for the reader to experience this daze that Jim is in, the chaotically episodic nature of his life over a period of several years, as he struggles to stay alive. Even though he periodically wonders where his parents are, even wonders what they look like, his main focus is on staying alive. His body suffers malnutrition. He develops pus-laden gums.

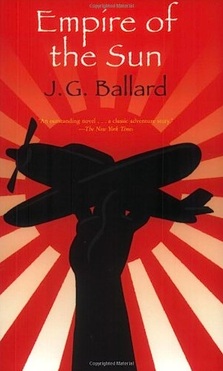

In my Kindle I highlighted the word sun, sunlight, and many synonyms for the word. Ballard seems to be saying two things. One, the Japanese empire, whose symbol seems to be that big red sun on its flag, is stretching its domain to include China. The sun also seems to symbolize a brighter day for Jim and the thousands of other refugees of their war. Ballard’s use of it is never heavy-handed; the “sun” just seems to appear as a natural part of this war-torn world.

I’ve read other war (anti-war) novels: Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, Crane’s Red Badge of Courage, Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, Heller’s Catch-22, and others. This novel captures yet a different war, part of the Pacific theater, but it is seen through the eyes of a boy, who at times perceives things poorly because he is a child, and at the same time grasps what’s happening precisely because his innocence allows him to see the truth. And his point of view often allows him to sidestep the callous or evil actions or adults, even those who profess to be looking out for him. Ballard seems to cast little judgment over this war. It is only where this young man is trapped, alive, yet half dead. Ballard’s last paragraph works as a précis of his entire novel:

“Below the bows of the Arrawa a child’s coffin moved onto the night stream. Its paper flowers were shaken loose by the wash of a landing craft carrying sailors from the American cruiser. The flowers formed a wavering garland around the coffin as it began its long journey to the estuary of the Yangtze, only to be swept back by the incoming tide among the quays and mud flats, driven once again to the shores of this terrible city” (279).

NEXT TIME: MORE SHOTS OF BACKYARD BIRDS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed