A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

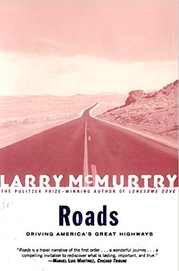

“I wanted to drive the American roads at the century’s end, to look at the country again, from border to border and beach to beach” (11). With this statement, McMurtry begins his travel book, which is not so much about the places he sees—although he does go into some detail about literary people, places, events—as much as it is about the roads that take him there. McMurtry loves to drive and not along those quaint roads where you can get stuck behind a slow-moving RV or semi, but the big ones, the Interstates. And every road he introduces with the article, t-h-e: the 15, the 40, the 35. He’ll often take a plane to a target city, rent a car, and drive back to his native Archer City in Texas.

Some nuggets:

“My casual intention, in thinking about these journeys, was to have a look at the literature that had come out of the states I passed through. For Minnesota there is not a whole lot. Scott Fitzgerald, though a native son, spent most of his life east of Princeton or west of Pasadena. His work seems to me to owe little or nothing to the [M]idwest. Louise Erdrich lives in Minneapolis now, but most of her work is set well to the west, near the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota” (30).

“Most Mexicans still feel that they have an innate right to be on the north side of the [Rio Grande] river, where their grandparents or great-grandparents lived. The Border Patrol can deport them, but it can’t extinguish this feeling” (54). If only Texans especially would understand this idea.

“Despite the Army Corps of Engineers’ elaborate strategies for controlling the lower Mississippi, most people who know and love the river know that it is more powerful than many plans human beings may design: one day it may rise up in flood and take out much of southern Louisiana, blowing through human constraints as easily as Moby Dick blew through the whaling boat” (68) LM wrote this in 2000. Not too prescient, eh?

“Once, when I was about ten, we were approaching the ranch after veering north to look at some pasturage when we saw a small barefoot boy racing along the hot road with terror in his face. My father just managed to stop him. Though incoherent with fear, the boy managed to inform us that his little brother had just drowned in the horse trough. My father grabbed the boy and we went racing up to the farmhouse, where the anguished mother, the drowned child in her arms, was sobbing, crying out in German, and rocking in a rocking chair. Fortunately the boy was not quite dead. My father managed to get him away from his mother long enough to stretch him out on the porch and squeeze the water out of him. In a while the boy began to belch dirty fluids and then to breathe again. The crisis past, we went on home. The graceful German mother brought my father jars of her best sauerkraut for many, many years” (185). This anecdote speaks for itself.

Occasionally McMurtry allows his prejudices to overpower his reason: “I’m not entirely comfortable in Idaho—fortunately it’s only seventy-five miles across the Idaho panhandle from Coeur d’Alene over the hills to Montana. I suppose my discomfort has to do with the Aryan Brotherhood and similar organizations, several of which make their official home in Idaho. In no state is there such obvious hatred of law and government—hard to explain, since there is scant evidence that there is much law and government in Idaho. A lot of frontier types who aren’t quite up to Alaska hang out there, secure in the knowledge that they’re in part of the country where the outlaw mentality is still encouraged” (195).

And talk about hatred of government: once when I was on a trip with forty other West Texans to visit the city of Ottawa, Canada, a majority of my fellow travelers booed the very mention of our president’s name. You see, this particular bakery had dared to rename their maple leaf cookie the Obama cookie. I never felt so ashamed to be an American in my life. I personally HATED George W. Bush, but I NEVER would have booed his name in any public setting, particularly in a foreign country—because much as I detested him and his policies, he was still my president. Larry, please, no more generalizations about people who hate or don’t hate. They’re just not relevant. We are all capable of hate in almost any context. I certainly won't let this one slip prevent me from loving your book!

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed