A WRITER'S WIT

The difference between life and the movies is that a script has to make sense, and life doesn't.

Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Born February 11, 1909

I watch as he gingerly undoes the thin cambric material concealing his box springs and pulls out a miniature copy of the Adventures of Tom Sawyer. “Found it on my teacher’s desk in fifth grade,” he whispers. “I’ve read it like twenty times.” He replaces it by wedging it between a spring and the mattress. Untying some strings, he produces a jar filled with grasshopper legs.

“Gross, dude,” I whisper, and he giggles, tying the jar back in place. He produces a small jewelry box.

“Here, open it.” I do and inside there’s a gold ring with a red stone. “It’s my Meemaw’s high school ring.”

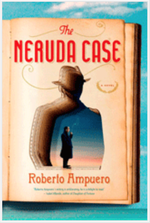

My Book World: On Neruda's Case

Ampuero’s novel, The Neruda Case, is divided into five parts, each one named after a woman whom Pablo Neruda is involved with over his lifetime, either as mistress or spouse. This novel is one of those in which a historic figure, in this case, a distinguished South American poet, is employed as a fictional character (names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously).

A kind of realization of Neruda’s life, the novel takes place against the backdrop of a pre-Pinochet Chile. In the early 1970s, Cuban Cayetano Brulé meets Neruda at a party, and the poet hires Brulé to help him locate a daughter he never really knew, the only child he believes he ever sired. Even though Brulé has never worked before as a detective, he agrees to help Dan Pablo.

In the part titled “Josie,” Brulé realizes Neruda has cancer, and the poet first engages him to locate a certain oncologist in Mexico. Brulé’s “training” as a sleuth takes place by way of reading certain detective novels that Neruda recommends. Throughout the novel, Brulé compares and contrasts his methods, his capabilities, with the fictional detectives of this one author. In order to make Brulé look like a detective, Neruda dresses him, presenting him with a lilac-colored tie dotted with small green guanacos (llamas): “It had a coarse texture, though a nice feel. On the lilac background, the guanacos leapt joyfully, grazed placidly, or contemplated the horizon” (55). Don Pablo declares the tie is over forty years old. He wore it when he met “some of the greatest European intellectuals” (55). He also wore it when he “went underground” in the 1950s. Essentially, Neruda means for the tie to be a talisman, to bring Brulé luck as he heads out on his mission to find Neruda’s daughter. This visual cue appears many times throughout the novel. Is it also a motif representing Don Pablo when he is not present? A reminder of Brulé’s mission, his amateur status? One is not quite sure, but it is one of those delightful images that makes the reader feel that he’s returned to familiar ground.

Throughout, author Ampuero recaps certain points in order to keep the reader apprised (and interested): “My women never gave me children. Not Josie Bliss, who was a tornado of jealousy, not the Cyclops María Antonieta, who gave birth to a deformed being; nor did Delia del Carril, whose womb was dried up when I met her; nor Matilde, who had several miscarriages. I’ve had everything in life, Cayetano: friends, lovers, fame, money, prestige, they’ve even given me the Nobel Prize—but I never had a child. Beatriz is my last hope. It’s a hope I buried long ago. I’d give all my poetry in exchange for that daughter” (132-3).

Oh, come on! one has to say. Really? Such a statement makes for good character motivation, but would a renowned poet have said such a thing?

Brulé’s trip continues throughout the world, including East Germany’s Berlin. One comes to believe that each of the five women in Don Pablo Neruda’s life has inspired him to be the poet he becomes; each is an integral part of the work that expresses the human being he is. Without each, or by remaining with only one woman, he would never produce the work that he does. With three chapters to go, Neruda dies, and Brulé is never able to inform the poet the truth about his daughter. As part of the novel’s denouement, one sees the lilac tie with green guanacos three more times:

“He wiped his tears with his guanaco tie, and studied the corpse’s face again through the shadows” (361). This seems to be Brulé’s way of connecting with the poet one last time.

The way is not easy, in the time of great political upheaval, but Brulé is able to attend Neruda’s funeral. “He wore his best suit, a white shirt, and the violet tie covered in small green guanacos” (363).

“He bit his lips, still unable to place Ruggiero, who now pressed his index finger against Cayetano’s green-and-purple guanaco tie, and smiled. ¶ ‘A friend of mine pushed you into that truck,’ he said. ‘They took you to Puchuncaví” (371). This scene brings Brulé full circle to the point where he was at the beginning of the novel.

The Neruda Case is a very finely constructed and enjoyable novel—not only as a sophisticated whodunit, but as a literary novel, as well. And even though I usually dislike reading translations (something is always lost), this one is superb. Read it!

WEDNESDAY: PHOTOGRAPH AND SHORT ESSAY

RSS Feed

RSS Feed