A WRITER'S WIT

That a majority of women do not wish for any important change in their social and civil condition, merely proves that they are the unreflecting slaves of custom.

Lydia M. Child

Born February 11, 1802

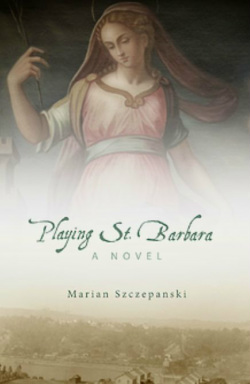

Playing St. Barbara Not Easy

In October author Marian Szczepanski wrote a guest post in this blog about how she came to pen her book. Before beginning my profile, you may wish to click on her name for a link to that post.

Publishing a book today is as dependent on word of mouth as it has ever been, more so if you consider that most publishers either don’t have the budget for reading tours and other expensive forms of publicity or else save their millions for their top-earners. What follows is my word-of-mouth entreaty to read a fine book.

A COMPELLING STORY

Playing St. Barbara begins in 1929 with an eighth-grader’s winning essay describing the seventh-century legend of St. Barbara, patron saint of miners. The salient features of Barbara’s life—a cruel and unyielding father, her unbending conversion from paganism to Christianity, her apparent disappearance into the earth—play out in various ways throughout Szczepanski’s novel, and it is important for the reader to internalize the saint’s story before moving on.

The narrative reveals the lives of three daughters, one of whom writes the winning essay, and the wife of a coal miner, primarily during the decade of the 1930s in southwestern Pennsylvania. As an aside, in 1957, my family’s car broke down in a coal mining town in this region, and we spent three days there in a “hotel” waiting for our car to be repaired (my parents wound up buying a new Pontiac before we returned to our home in Kansas). Coal dust was so prevalent that my mother felt compelled to wipe every chair before we sat down, even the toilet seat. She must have prayed before each meal we ate, that we would not breathe in any more of the powder than necessary. Such fine dust is spread throughout this story like a black veil.

The father, Finbar Sweeney, is an abusive brute. Not a day goes by that he doesn’t verbally abuse his wife, Clare, or physically harm her by way of a brutal slap or unwanted sexual advances. Not a day goes by that he doesn’t abuse one of his three daughters. All three seem like shards of the same person, and they are, in a sense, all reflections of their mother, Clare. It may be because of their suffering that Clare in some way consumes what seem like magic seeds to free her body of a number of pregnancies.

One bright thread in the lives of the coal miners and their families is the annual St. Barbara pageant (the other is baseball), offered up to the martyred life of the patron saint of miners. Each of the Sweeney daughters, very close in age, is called upon to play the life of the saint over several years—and each in her own way fails. The event emphasizes the class differences in that the play is directed by a woman the youths call The Queen, a wife of an “upperhiller,” a woman whose husband is in management. However, The Queen must depend on the miners’ children to play the parts and is not always pleased with their performances.

Each of Clare's daughters, in her own way, manages to escape from the town: the eldest by marrying well, another by becoming a nun, though she sacrifices her own love of a man to do so, and the third by her very wits, bidding good-bye to the town and venturing off to nearby Pittsburgh to start a new life. Clare, too, long-suffering wife must make a decision with regard to Finbar. After the mine experiences a huge explosion and collapse and Fin must spend time in the hospital, she goes to see him every day, and each day, unless sedated, he lashes out at her. Temporarily free of his ill treatment at home, she, of course, drinks in her freedom. Her friends and daughters urge her to leave Fin, an act of desperation at a time and place where the strictures of the Roman Catholic Church are clear, where most women wouldn’t leave their husbands for any reason. But the women in Clare’s life are clear: Finbar, alcoholic brute, is never going to change.

BUY THE BOOK

Playing St. Barbara is a rich amalgam of many things: historical novel, romance (capital R), crusade for the rights of nonunion workers (Pennsylvania Mine War of 1933), exposé of the Klu Klux Klan’s work in the 1930s, the plight of women since time immemorial. But most of all, it is a window into a small fragment of life that must have begun somewhere in Germany, where coal-mining was developed long ago, and continues through today in the States. Though the conditions and rights of miners have improved, the delicate and flammable nature of their work will probably never change. And sadly, though the lives of women everywhere have improved, as well, there are still souls today who are being subjected to men like Fin, trapped in lives that are as dark and dirty as the mines themselves. Szczepanski’s book will not allow us to forget.

Today’s writers depend heavily on the “platform” they themselves build: websites, blogs, readings in indie bookstores (that they themselves must arrange), Facebook pages, Twits (you know what I mean), Google+. But most of all, steady sales depend on the hardy word-of-mouth transfer from one reader to the next. Marian Szczepanski has written a highly literate and transformational book. It is a book for women. It is a book for men. It is a book for the old and the young. Anyone who loves a great story, a significant one. To get your copy, click on any of the links below. I highly recommend that you do!

Amazon

High Hill Press

Powell’s Books

As an added note, click here to follow a link to Marian's website for a PDF of the cast of characters and a number of other aids for readers, as well.

WEDNESDAY: PHOTOGRAPHY

RSS Feed

RSS Feed