A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

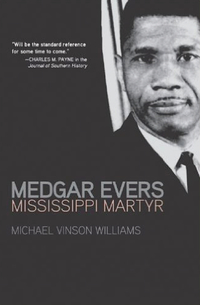

I turn fifteen on June 11, 1963, a day before NAACP field secretary for Mississippi, Medgar Wiley Evers, is assassinated by Byron De La Beckwith, in front of Evers’s own home in Jackson, Mississippi. If the item is mentioned in the local media where I live in Wichita, Kansas, I am probably oblivious to it. Yet Evers’s death seems to kick off a series of political assassinations that take place in the United States in the 1960s: John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert Fitzgerald Kennedy, and others. In spite of all its many charms—Motown, the Twist, the miniskirt, mod clothing, the Sexual Revolution—the decade is really a rather dark period.

Evers’s story, through the years, is one that echoes in my mind—as it is occasionally referenced on TV, in the news, or even a film—yet I never quite have the narrative of events straight, the motivation for such a heinous act. But after reading Mr. Williams’s book, I can never look at the 1960s in quite the same way. The life of Medgar Evers is a remarkable one, a life that is often overlooked in the larger scheme of things, for example, that Mississippi is the wealthiest state among all the southern states, up until the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, that its wealth and position are entirely dependent on the institution of slavery and that when it is abolished, the South, including illustrious Mississippi, descends into poverty.

Contrast that status with the Mississippi of today, which holds the dubious distinction of being one of the poorest states, with the poorest level of per capita spending on education. What a descent, and yet it helps to explain why, even a hundred years after the Civil War—that’s at least four generations—white Mississippians still hate Negroes in the 1960s, want to keep them suppressed. Yes, for those one hundred years, people with dark skin are still enslaved by draconian laws that keep them confined to their own schools, their own restaurants, their own libraries (if such exist), or their own sections of public places such as train stations or washrooms. And certain (not all) white Mississippians believe that to continue such segregation is not only all right but that it is somehow ordained by God. And furthermore, certain white Mississippians feel justified in using lynching to justify their rage over the stupidest kinds of slights imaginable: winking at a white woman, slapping a white boy, a fifty-cent debt.

Imagine your family trying to move about your daily life—school, work, church, social intercourse—and always being afraid you might offend or displease someone with white skin. You’re often told you don’t belong in this line, this room, this particular place, and often, in spite of certain signs—Coloreds Only—you’re not always sure, until someone with no uncertainty informs you, either by way of verbal abuse or physical, sometimes violent, actions. This is the kind of society that Medgar Evers is attempting to change in his work as NAACP field agent. Several times in his life, Evers could leave the state of Mississippi for attractive job offers in more enlightened spots in the country, but he loves his home state, its geography, its people, so very much that he chooses to stay and fight.

Unlike MLK, Evers is not necessarily swayed by the use of peaceful means. He keeps a revolver in the glove box of his car, as he often travels late at night, arriving home in the dark after having attempted, somewhere else in Mississippi, to help others negotiate the filthy waters of prejudice and desegregation. Evers speaks out, both verbally and in print. His assassination does not happen out of the blue. Prior to this event, he narrowly escapes being hit by a police car. His household receives threatening phone calls. For a time he does accept or ask for protection, and for a time he receives it. But finally, Evers realizes he can never be free to do what he needs to do for the African-Americans of Mississippi if he must constantly have body guards surrounding him, and besides, it becomes too expensive of a proposition and he begins to eschew the offers.

And you may be thinking, All this is old ground, covered a thousand times in the past. Why don’t we just move on and forget about it?

If that’s what you think, consider these passages from forty-year-old writer Ta-Nehisi Coates’ article in The Atlantic’s September issue, in which the author addresses his son in light of his own fears:

“And yet I am still afraid. I feel the fear most acutely whenever you leave me. But I was afraid long before you, and in this I was unoriginal. When I was your age the only people I knew were black, and all of them were powerfully, adamantly, dangerously afraid” (85).

And Coates’s fear is not only present in Baltimore where he grows up, but in the North, when he visits a grandmother:

“I felt the fear in the visits to my Nana’s home in Philadelphia. You never knew her. I barely knew her, but what I remember is her hard manner, her rough voice. And I knew that my father’s father was dead and that my Uncle Oscar was dead and that my Uncle David was dead and that each of these instances was unnatural. And I saw it in my own father, who loves you, who counsels you, who slipped me money to care for you. My father was so very afraid. I felt it in the sting of his black leather belt, which he applied with more anxiety than anger, my father who beat me as if someone might steal me away, because that is exactly what was happening all around us. Everyone had lost a child, somehow, to the streets, to jail, to drugs, to guns. It was said that these lost girls were sweet as honey and would not hurt a fly. It was said that these lost boys had just received a GED and had begun to turn their lives around. And now they were gone, and their legacy was a great fear” (85).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed