A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

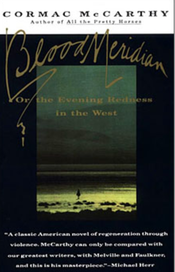

It might be that McCarthy brings to fruition that which Hemingway and Fitzgerald could not—due not only to publishing constraints concerning swear words and graphic violence but also the reins the authors may have held tight on themselves. The makings of complete literary honesty were there via Hemingway’s forthright sentences, at times extended to paragraph length (with little inner punctuation) and Fitzgerald’s fortitude in portraying the brutality of capitalism’s clutches on early twentieth-century America. But in this novel, McCarthy returns to the latter half of the nineteenth century of the West to extend his page-long sentences lyrically to rival the two authors mentioned before. And he does so in a way that somewhat softens the inherent mayhem of this novel.

At first, I had some difficulty in following the plot: that a sixteen-year-old Tennessean (the kid) ventures to the Southwest to see what’s in store for him there. The kid is tough, though, and becomes tougher as time passes. He joins a band of men who seek to scorch the earth of natives and anybody else with dark skin (the N word, due to Twain’s use of it in his books, seems to be used without restraint by these characters). But as the book shifts from one episode of killing to another across this physical and moral wasteland, I sense that the narrative is largely impressionistic. I am reminded of Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage—the wildly episodic nature of war—for that’s what this book is about, the White Man’s war to tame the West and all its human and animal critters.

Other than superficial features, the characters, as such, show little traditional development, but that may be McCarthy’s intent. These killers act as a single body, it would seem. In fact, little tolerance for the individual exists here. You act with the others, or you are fighting for your own life. And as an impressionistic work can be dreamlike in which a figure returns to you dream after dream, these characters keep running into each other, regardless of the miles and days or months between them. They can’t seem to remove themselves, if they should desire to, from this wanton way of life or death. And in most cases, it is the latter that guides them through their days heading toward McCarthy’s oft-cited orange sunset or that blood meridian.

NEXT FRIDAY: My Book World | Jaime Manrique & Jesse Dorris's Bésame Mucho: New Gay Latino Fiction

RSS Feed

RSS Feed