A WRITER'S WIT |

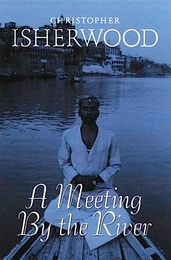

I'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the eighteenth in a series of twenty-four.

My Book World

Isherwood’s final novel, Meeting is both enjoyable and frustrating to read. The story of two brothers—told mostly in an epistolary fashion—holds one’s attention most of the time. The prose, as always, is seductive, leading a reader from one sentence to the next, one letter to the next. The author’s grasp of his material, that one of the brothers, Oliver, is planning to become a Hindu monk, is quite adequate—based on his own extensive study of and participation in the religion.

But the storytelling seems facile at times. The plot becomes a bit more complex when the other brother, Patrick, is married but is having an affair with a young man named Tom. Oliver finds out rather by accident and is unmoved by it, stating that from the standpoint of being Hindu, he doesn’t care. What is odd and a bit disconcerting is that none of the letters that Patrick or Oliver writes is ever answered directly. They both dutifully write their mother, and Patrick writes his wife. However, except for very rare indirect references to their responses, all of the information is outgoing—limiting the scope of the narrative, no doubt Isherwood’s intent. But why?

I located his thoughts concerning the novel from the second volume of his Diaries: “Yesterday I finished the first draft of A Meeting by the River; it has taken me exactly three months, to the day! I have just finished reading it through. There is something in it. But it seems quite boring in parts. Perhaps it needs cutting down to a long short story. It’s now 110 pages—let’s say a bit over 35,000 words” (367). I believe his instincts are headed in the wrong direction. He must add to it!

Isherwood also receives a response to a third draft from friend and writer, Edward Upward: “Obviously the reader isn’t meant to accept Patrick’s view that Oliver is becoming a monk in order to escape the ambitiousness which is natural to him but which he knows their mother wouldn’t approve of in him . . . . On the other hand the reader can’t quite believe that Oliver becomes a monk solely because the social work he’s been doing doesn’t seem ‘real’ enough to him” (400). Diaries.

I believe this observation is what makes the novel not as strong as it might be: one is never convinced of either character’s viability. One doesn’t learn enough about Oliver’s former social work to be able to compare it to what he might accomplish as a monk. One doesn’t quite believe that Patrick works in Hollywood, that he either loves his wife and children, or that he loves Tom, his paramour. And both characters, because of the similarities in their prose, might as well be two manifestations of the same character! Though Isherwood talks himself and his editor into publishing the book in this condition, there seems to be a lot missing. It, like A Single Man, is only about 50,000 words. If Isherwood could have added at least 30,000 words and developed both characters to their fullest, if he could have used the letter writing to its fullest capabilities, the reader might have become a bit more compelled to care about either brother and what happens to him.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed