A WRITER'S WIT

“A few times in my life I’ve had moments of absolute clarity. When for a few brief seconds the silence drowns out the noise and I can feel rather than think, and things seem so sharp and the world seems so fresh. It’s as though it had all just come into existence. I can never make these moments last. I cling to them, but like everything, they fade. I have lived my life on these moments. They pull me back to the present, and I realize that everything is exactly the way it was meant to be.”

Christopher Isherwood, from his novel, *A Single Man*

Born August 26, 1904

My Book World

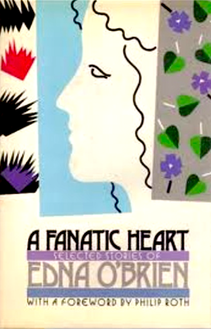

These twenty-nine stories are the best plucked from four of O’Brien’s prior collections plus four previously unpublished stories. Yet when I read them, they all seem of a kind: all of them taking place in various decades of her native Ireland. Moreover, one hears the same bells going off in different stories, but always with a slightly different timbre. One of these ringing motifs is men who drink heavily and cause one kerfuffle or another for the women in their lives. Is it the hard edge of Irish life itself—the damp cold, the grinding poverty—that cause men to act badly, or is it a man’s will to do so? Another motif is brash women who yet still have a small fear of the Catholic church, its strictures. And yet another one is the woman hungry for the flesh of love, whether it is with a man or a woman. And yet each time O’Brien presents the reader with one of these jeweled motifs, it is fresh, not much like the bell that went off previously. The collection might be compared to a musical form: variations on a theme, in which these various themes crop up again and again until their final rendering is heard.

One of my favorite stories is “Sister Imelda,” in which a teenage girl in a Catholic school falls in love with her teacher, also a nun. It is a love that is mutual, and yet her friends only think she is sucking up to the sister. No trouble arises. The turmoil between them—whether they should associate in any way but as teacher and pupil—lies just beneath the surface. And then Sister leaves the school.

“I knew that there is something sad and faintly distasteful about love’s ending, particularly love that has never been fully realized. I might have hinted at that, but I doubt it. In our deepest moments we say the most inadequate things” (143).

“Then she knelt, and as she began he muttered between clenched teeth. He who could tame animals was defenseless in this. She applied herself to it, sucking, sucking, sucking, with all the hunger that she felt and all the simulated hunger that she liked him to think she felt” (214).

“She had joined that small sodality of scandalous women who had conceived children without securing fathers and who were damned in body and soul. Had they convened they would have been a band of seven or eight, and might have sent up an unholy wail to their Maker and their covert seducers” (252).

NEXT TIME: PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAY OF A PARADE IN RENO

RSS Feed

RSS Feed