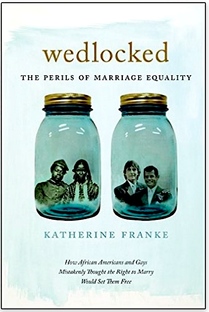

A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

Ms. Franke, Sulzbacher Professor of Law and Director for Gender and Sexuality Law at Columbia University, puts forth an interesting, almost quirky thesis for her book. She believes that same-sex couples receiving the right to marry is similar to laws that compelled African-American men and women who had been co-habiting prior to the end of the Civil War, to marry following its end. And she asserts some compelling arguments or at least some ideas to ponder.

In her introduction, Franke states: “State licensing means your relationship is now governed by law, and that you have to play by law’s rules. An affair or a breakup now has legal in addition to emotional consequences. Put most bluntly, when you marry, the state acquires a legal interest in your relationship. Cloaking freedom in state regulation—as the freedom to marry surely does—is a curious freedom indeed, for this freedom comes with its own strict rules” (9).

The author points up a number of problems with marriage equality, one of which is the following: “Given that sexual orientation-based discrimination is legal in twenty-nine states, many Americans in same-sex relationships find themselves in the situation where they have a right to marry but exercising that right could result in losing their job once their employer learns of their marriage” (59).

“Lawyers who advise non-traditional families on their legal rights have noted that once states started to allow same-sex couples to marry, the rights of couples in non-marital families began evaporating. Whether it be relationship contracts between unmarried partners, de facto parental rights, or rights that might accrue between two partners as a matter of common law, little by little courts are saying: you could have married, and since you didn’t we won’t recognize you as having, or being able to create, any kind of alternative family relationship between or among you that is legally enforceable. The right to marry, thus, extinguishes a right to be anything else to one another” (98).

Franke later reasserts what she claims in her introduction, which is worth repeating, for it seems to reinforce her thesis: “Getting married means that your relationship is no longer a private affair since a marriage license converts it into a contract with three parties: two spouses and the state. Once you’re in it you have to get the permission of a judge to let you out. And what you learn when you seek judicial permission to end a marriage is that it’s a lot easier to get married than it is to get divorced” (121).

As Franke begins to conclude her arguments, she often shifts to speculative language. “Of course we can’t know for sure, as the court documents tell us far too little. But I have a couple of guesses about why these unwed mothers went to court and filed form papers announcing the fathers of their children” (174). “Another possible explanation for the frequent filing of bastardy petitions was the mothers were initiating these cases not for a local legal audience, but for one up north” (176). “It’s not hard to imagine unmarried mothers’ turn to ‘bastardy petitions’ as a way of healing the deprivation of kinship that all enslaved people suffered” (177). “The police had been summoned by another of Garner’s lovers who was jealous and had reported to the police that ‘a black man was going crazy’ in Lawrence’s apartment ‘and he was armed with a gun’ (a racial epithet rather than ‘black man’ was, in fact, probably used)” (181). Well, which is it: “probably” or “in fact”? The latter example, in particular, seems inauthentic if the author cannot, in fact, locate a proper citation to prove her assertions.

Near the end of her book, Franke sets up an important and stimulating question: “One might also provocatively ask whether marriage is better suited for straight people. By posing this question I don’t mean to align myself with those, such as the conservative National Organization for Marriage, who feel that only straight people should be allowed to marry, but rather to ask whether the legal rules and social norms that make up civil marriage have heterosexual couples in mind. Put another way, is there something essentially heterosexual about the institution of marriage? Are marriage’s rules and norms well suited to govern the lives and interests of same-sex couples?” (209). Yes or No? Her question would make for an interesting debate!

“One lesson we can draw from the early experience of same-sex couples with the right to marry is that marriage may not be for all of us. While we might all support the repeals of an exclusion from marriage as a matter of basic constitutional fairness, we need not all jump into marriage to demonstrate our new rights-bearing identity. If this book has any overarching message it is that we ought to slow down, take a breath, and evaluate whether marriage is ‘for us’” (225).

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed