My Book World

Cover of Hertog's 2012 Book

Cover of Hertog's 2012 Book by Susan Hertog

Both of these writers were born in the early 1890s, same as my late grandmothers, but neither one of my grandmothers experienced even a tenth of the excitement that these women did. But then my grandmothers wound up with something these two women didn’t: men who loved them enough to stay with them for life.

Rebecca West, British, and Dorothy Thompson, American, were both writers and became fast friends. Early on West was married to H.G. Wells, but the marriage did not last. Though West did remain with another man for over thirty years, in the end it was not a satisfying relationship. Dorothy was married to Sinclair Lewis, and though she was thrilled by his career and lived in support of it, she didn’t exactly receive the same enthusiasm in return for her award-winning work.

Both women gave birth to a son each, both of whom would be troubled largely, they proclaimed, because their mothers pushed them away in favor of their careers (yet each had an equally self-absorbed father). West’s son would go so far as to portray a likeness of his mother in a novel that she did not sanction. They never spoke after its publication.

Biographer Hertog does a fine job of comparing and contrasting the women’s lives by way of alternating chapters. Even better is her assessment of the place these women hold in literary history, plowing the way for women of succeeding generations.

Some Nuggets:

Rebecca West

“Perhaps it seems facile to connect her loss of H.G. to the abrupt abandonment by her father, but Rebecca would always espouse Freud’s theory of unconscious responses that fan out from a traumatic core connecting one’s past to one’s present” (41).

West’s “female protagonist concludes that ‘Every mother is a judge who sentences the children for the sins of the father’” (79).

West said, “‘I love America and I loathe it.’ She loved its land, lakes, and rivers but loathed its phony materialist culture” (88). Hmmm. Even then.

“Rebecca refused to say ‘obey’ as part of her marriage covenant, and Henry [Andrews], perhaps at her behest, substituted ‘share’ for ‘endow’ when he pledged his bride his worldly goods” (129).

“To deride was to deflect vulnerability. To write was to wield power and control. From ten in the morning until one in the afternoon, Rebecca sat in her study with a series of writing tablets, one designated for each draft of her book and a pen to suit each stage of its evolution” (174).

Dorothy Thompson

Dorothy “was convinced that ‘every worker needed a wife’” (204). We heard it here first.

“‘The whole nation lived on futures, mortgaging tomorrow’s wages for today’s automobile or radio and the feverish turnover of goods was called prosperity,’ she wrote. ‘Our finest cities are disfigured by dark, unhealthy, crime-breeding slums. We admire success and are callous to achievement’” (239). What a seer!

Friends

“Like Rebecca, Dorothy was deemed an androgynous creature, with ‘masculine’ tastes and ambitions. Out of sync with their time, yet deeply, longingly feminine, neither knew how to be a woman” (260). Whoa. Do you agree with Hertog?

“Rebecca and Dorothy were delusory when it came to love. They projected idealized stereotypes onto their men, and demanded more of them than any man could fulfill. Given their emotional deprivation as children, and their impulse toward social legitimacy, there was no amount of piety for Dorothy, or psychoanalysis for Rebecca, that could compensate for the emotional damage they caused and incurred. And the men they chose—Joseph Bard, Sinclair Lewis, H.G. Wells, and Henry Andrews—were equally crippled” (434). Whew!

Hertog’s selected bibliography includes all of West’s and Thompson’s major works, should one choose to read them. I read West’s The Fountain Overflows because Jane Smiley included it in her Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Novel. I’m afraid my 2007 assessment wasn’t very substantive, but I’d be willing to tackle it again knowing now what I do about West.

Errata

This Kindle edition had at least a couple of typos: “gossping” and “lattter.” I wonder if the same typos exist in the print edition.

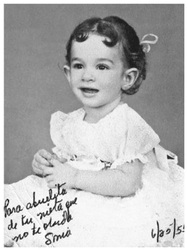

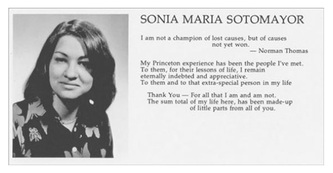

I became enamored with this book before I ever opened it by way of hearing Supreme Court Justice Sotomayor’s televised reading on C-Span’s Book TV. With great verve, wit, and charm, she enthralled a large crowd with the circumstances that led her to write a memoir in the first place.

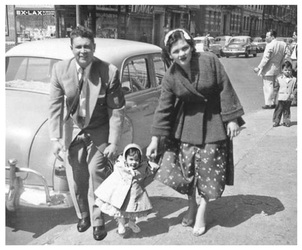

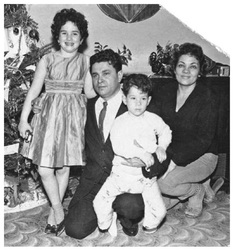

In speaking of her upbringing amid the multicultural arena of the Bronx, Justice Sotomayor says, “The differences were plain enough, and yet I saw that they were as nothing compared with what we had in common” (103). This understanding, early on, may lead Sotomayor to do something with her life that brings humanity together rather than tearing it apart.

“I honestly felt no envy or resentment, only astonishment at how much of a world there was out there and how much of it others already knew. The agenda for self-cultivation that had been set for my classmates by their teachers and parents was something I’d have to develop for myself. And meanwhile, there could come at any moment the chagrin of discovering something else I was supposed to know. Once, I was trying to explain to my friend and later roommate Mary Cadette how out of place I sometimes felt at Princeton” (135).

Sotomayor continues by describing her career develops, how each step leads toward her eventual nomination for the Supreme Court. Of her work in the district attorney’s office, “It was in effect to see that mastery of the law’s cold abstractions, which had taken such effort, was actually incomplete without an understanding of how they affected individual lives. Laws in this country, after all, are not handed down from on high but created by society for its own good” (212).

As I neared the end of the book, I found myself wanting the pages to stretch out; I wished for a delayed resolution to the narrative. Sotomayor, from the work she does while at Princeton on behalf of others less fortunate than herself, to her work in the DA’s office, to her work in a private firm where she earns a better salary and is befriended by important and wealthy people such as the Fendis of the fashion arena, is storing up years of valuable experience. In braving so many different worlds and mastering the language and rules of each, she smartly positions herself to become a judge, one who actually brings the law into focus for the rest of us. How many of the other justices, I wonder, have the breadth and depth of experience that she brings to the bench? If they know only the law and have had little touch with humanity, one wonders if their judgments aren’t sometimes a bit tainted by a certain provincialism.

I finished the last page having developed a great admiration for Sonia Sotomayor. She tells frankly of her life, neither diminishing nor embellishing any aspect of her background or character. When one writes with such candor, the reader can't help but feel drawn into the story. One has to think: Maybe, I, too, can be as honest as I tell my children and grandchildren about my life. I can’t wait to read her next book. As this one ends with her first judiciary assignment, I am positive there will be another.

P.S. I think West and Thompson would be delighted that Sotomayor is the third of four women to be appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States of America. I hope so. The battles they fought and won in the first half of the twentieth century, though not in the arena of law, should account for something.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed