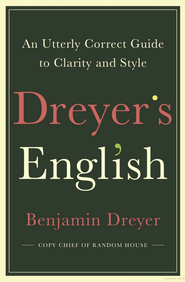

A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

This book about copyediting offers readers an excellent review if you think you already know the business pretty well, and, if you don’t, then it’s a great place to begin (Dreyer himself includes a list of fine sources). Even so, he makes something like the subjunctive mood (“mood” being a grammatical concept not always taught today) utterly clear (If I were vs. If I was)—not as rigid as, say, the Chicago Manual of Style. Dreyer nevertheless has his pet peeves and his absolutes:

This may be a particular peeve of mine and no one else’s, but I note it, because it’s my book: Name-dropping, for no better reason than to show off, underappreciated novels, obscure foreign films, or cherished indie bands by having one’s characters irrelevantly reading or watching or listening to them is massively sore-thumbish. A novel is not a blog post about Your Favorite Things. If you must do this sort of thing—and, seriously, must you?—contextualize heavily” (113).

I give Dreyer another thumbs up because he has a broad (flexible and forgiving) understanding of the English language, the concept of rhetoric being one of them. A peeve of mine (and he articulates it well) is how people misuse the term “begging the question” in common speech (especially on MSNBC or CNN) and writing, mistakenly taking it to mean “raising the question”:

Begging the question, as the term is traditionally understood, is a kind of logical fallacy—the original Latin is petitio principii, and no, I don’t know these things off the top of my head; I look them up like any normal human being—in which one argues for the legitimacy of a conclusion by citing as evidence the very thing one is trying to prove in the first place. Circular reasoning, that is” (151). The greatest example from my classical rhetoric text is, “When did you stop beating your wife?” An apparent single premise actually assumes two, one of which is not possible without the other. To stop beating your wife you had to begin at some point, making the question a trap.

At the same time, Dreyer is unusually forgiving about other concepts, some of which cause me to grind my teeth. Even a few scientists seem to forget that “data” are plural (hee hee) for “datum.” The data clearly show … (not “shows”). Same with “media.” The media are (not “is”) always talking about how the media are not to blame. Ah, so satisfying to my ear, and yet Dreyer seems to shrug it off.

Dreyer’s greatest talent may be as wordsmith. He makes this discussion of “continual” vs. “continuous” pellucid: “Continual” means ongoing but with pause or interruption, starting and stopping, as, say, continual thunderstorms (with patches of amity). “Continuous” means ceaseless, as in a Noah-and-the-Flood-like forty days and forty nights of unrelenting rain” (179).

He tackles “epigraph” and “epigram”; he tackles “farther” and “further,” and makes their meanings clear. Most of all, Dreyer’s book seems to demonstrate that the copyeditor, far from being captain of the grammar police, exists to take a writer’s finished manuscript and style his or her words to make the final product seem more like the original than the original. In other words, the copyeditor’s work should be invisible. Well done, it seems like magic, particularly to the author.

NEXT FRIDAY: My Book World | Matt Bell's novel, Appleseed

RSS Feed

RSS Feed