A WRITER'S WIT

Too much rest is rust.

Sir Walter Scott

Born August 15, 1771

My Book World

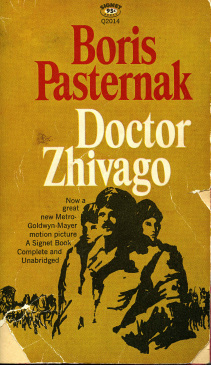

The Tattered Cover of My Copy

The Tattered Cover of My Copy As a high school youth I saw the film Dr. Zhivago at least twice. Then when I went to college I was required to view it for a humanities class, whose theme for the semester was “creativity.” Among other titles we also read Leo Tolstoy’s What is Art?. The book cost a dollar. One evening early in the semester the entire college, who was required to take humanities, showed up at the local theater to view Dr. Zhivago; the venue was capable of holding all 700 of us. Even out of the three showings all my tender mind could derive from the three-hour film was that Dr. Zhivago simply wished to live his life, free of political wranglings. He had no thoughts of being rich; he merely wanted to live his life creatively—mainly through writing poetry. Through the years I’ve continued to revisit the film, and, as an older man, derive different gifts from it.

Back when I was in college I was not required to read the novel but bought a Signet paperback version (the cover says) for ninety-five cents. I estimate that Dr. Zhivago, the novel, moved with me at least a dozen times from Winfield, Kansas to Dallas to Lubbock, Texas, each time packed up in a box and then placed in its alphabetical niche on various shelves. But only recently did I find the time to pull the yellow-paged copy off the shelf and read it—close to fifty years after I bought it. I’ve not been disappointed in Pasternak’s novel first published in Italy in 1955. It caused a furor both in Russia, where it was officially denounced, and in the Western world, where it was heralded as a realistic account of Tsarist Russia’s shift to communism.

The plot, of course, is only too familiar. Dr. Yuri Zhivago comes from a rather well to do family, and he receives his education with grace and anticipation of living a charmed life. He marries Tonia, and they have a son. At some point he works with Lara, a nurse, and though he is attracted to her, he does not admit it. Years later they are reunited by working in the same hospital, and they fall in love. Zhivago is then swept up in Russian history as he is captured by the partisans, who conscript him as a medical officer. He “serves” with them for a long period, and he never again sees Tonia or his son, Sasha, who have moved to Paris. As an older man he marries and fathers two children, but this part is left out of the film. Unlike the film, which seems to conclude with Yuri’s heart attack on the street, the book ends with a detailed account of the life of Tania, the love child of Yuri and Lara. The film devises a frame by which Zhivago’s brother searches out Tania and the entire book seems to be told as one flashback.

“Zhivago had told him how hard he found it to accept the ruthless logic of mutual extermination, to get used to the sight of the wounded, especially to the horror of certain wounds of a new sort, to the mutilation of survivors whom the technique of modern fighting had turned into lumps of disfigured flesh” (99).

“On one stretcher lay a man who had been mutilated in a particularly monstrous way. A large splinter from the shell that had mangled his face, turning his tongue and lips into a red gruel without killing him, had lodged in the bone structure of his jaw, where the cheek had been torn out. He uttered short groans in a thin inhuman voice; no one could take these sounds for anything but an appeal to finish him off quickly, to put an end to his inconceivable torment” (101).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed