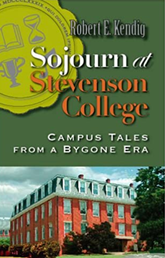

A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

This book is a satisfying read because the author opts to tell his story of teaching in a college town in the 1930s in a nonlinear manner. Although some characters carry over from one chapter to the next (like a meddlesome underling in the history department), each tale can more or less stand alone.

This book has its poignant moments, but it is largely about humor:

A filling station owner installs a large speaker under the seat (ew) in his customer outhouse and connects it to a microphone. “‘Lady, would you move over please, we’re working down here’” (46-7).

At Stevenson College, students are a bit perturbed because the faculty are “unnecessarily indolent” (78) in standing for the opening and closing hymns. “During the holidays, some of the students—we never knew who were the guilty ones—gained access to the chapel. They ran uninsulated wires through the tops of the cushions on the front pews, and under the carpeting on the floor to the loud foot pedal of the piano and thence to a substantial dry cell battery located to the rear of the instrument” (79).Well, one can imagine that on that day, every faculty member stood for the opening and closing hymns.

Later, the meddlesome underling commandeers the visit of a literary figure from England, attempting to make his visit as English-like as possible, even to the point of faking a British accent in what is probably a mid-South community. All throughout she rudely attempts to guide the discussion away from the local department and what and how the professors teach. Finally, when the woman expresses her fascination with the spelling of British names, the Brit himself has had enough: “This was more than Sir Reginald could stand. He sat upright in his chair and, looking directly at Mrs. Garber, he responded, ‘No, madam, I am not hyphenated. I am not even circumcised!’” (108).

The story that may touch educators comes near the end when Kendig renders how he advises a star pupil who, upon graduating, has the opportunity either to play a professional sport or take advantage of a Rhodes Scholarship. The pupil asks Kendig what he ought to do. The esteemed professor asks him to ponder the following: “But think about the two opportunities ahead of you and assume for a moment that either one can lead to your being famous. Then you might ask, ‘For what would I want to be famous?’”(165-6). I won’t say which he chose.

This is one of those books published by a small press that may not be picked up because it is “too parochial or too regional” in its nature. Yet it is a book that is well edited, well-designed, and one that is both enlightening and entertaining. Kudos to publisher/editor Barbara Brannon for bringing this book to light for all of us.

NEXT FRIDAY: My Book World | Samuel Butler's The Way of All Flesh

RSS Feed

RSS Feed