A WRITER'S WIT

We breathed the air of freedom without knowing the language or any person.

Nelly Sachs, Poet

Born December 10, 1891

My Book World

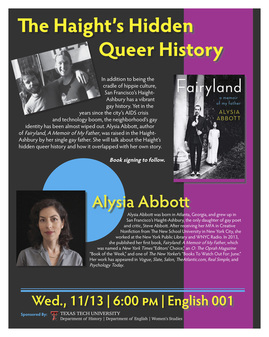

On November 13, 2013 I attended a reading at Texas Tech University. There Alysia Abbott, author of Fairyland, read from her memoir about growing up in the seventies under the parenting of her father, who was gay.

During her presentation, Abbott gave more history and background about the time period than she spent reading from the actual text, which was a bit disappointing. Perhaps she felt, since she was addressing history as well as English students, that she must give more information to such a youthful audience.

At any rate, Abbott’s book is what a good memoir should be: a point of view that is composed from the inside-out, a story few others could tell. When she is a tot, her mother is killed in a car accident in Atlanta, Georgia. Her father Steve Abbott, bisexual up until that time, bundles up his daughter and moves to San Francisco. There he finds solace in a Bohemian community of poets, from whom he gains great sustenance. He could have left his daughter with her maternal grandparents in small-town Illinois, but he chooses to raise her in this milieu of social and political freedom.

Even though he has opted to live in the freest gay community in the country, Alysia assimilates a rather closeted attitude by virtue of the fact that she must keep her dad’s gay life a secret from the rest of their family when she visits them. And because of this attitude, she too, feels as if she’s closeted. In fact, she often keeps her dad's sexuality a secret from her friends at school, for as long as she can. Even when she attends school in NYC and later in Paris, she does not easily reveal her secret—afraid it will make her different.

When her father becomes ill with AIDS in the early nineties, she must put her academic and personal lives on hold and return to SF to care for him. When she hesitates, he asks her to recall that when her mother died, he didn’t have to take care of her, but he chose to. Dagger! She winds up caring for her father thirty or forty years earlier than most people care for their elderly parents, and it does cramp her robust life. When he enters hospice care, she is relieved. Still, she must make daily pilgrimages to see him, must remember to take him certain items he asks for or things she knows he wants. Each day becomes more difficult.

Abbott has slowly built the narrative arc leading toward a powerful and inevitable climax: her motherless state and search to find surrogates, the San Francisco earthquake of 1989, which becomes a metaphor for the fissure in the relationship with her father, her cross-country pursuit of education, when she could have stayed in California, and her return from Paris so that she can finish her degree hurriedly and rush home to witness her father’s death.

“I was studying his fingers when the mechanized rhythm of the breathing, which had been steady—and calming in its steadiness—suddenly paused. Everyone in the room stirred, the tension building as we waited for the next heaving inhalation.

It never arrived.

There was no sound at all.

Then at once everyone’s voices rose up in a single chant: ‘We love you, Steve. We love, you, Steve. We love you . . .’

I collapsed over my dead father’s hands and wept. Exhausted and relieved” (306).

“It didn’t occur to me until after Dad died that the lack of a long-term boyfriend in his life was due, at least in part, to my overarching presence in our apartment as a teenager. I scowled. I was rude. I neglected to deliver phone messages and objected when my father kicked me out of his bedroom/our living room. Except for my close attachment to Dad’s first two boyfriends, the men that passed through our life were mostly useless to me. They could never replace my mom. All they could do was take my father from me, divide his precious love in two” (308).

As usual, I've set up a link to Powell's Books, and, if the price isn't right, of course, you can find anything at the other place.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed