A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

I'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the thirteenth in a series of twenty.

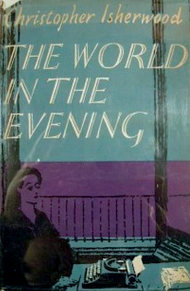

Evening. Minneapolis: U.of Minnesota

Press, 1952, 1982.

Evening, set in the late 1930s and early 1940s, seems to be hung on a simple frame. Part One is entitled “An End.” In it the protagonist, Stephen Monk, catches his second wife, Jane, in a compromising position with another man and leaves her immediately—almost too easily, it seems. Isherwood introduces a number of principle characters, including Stephen’s “Aunt” Sarah, as well as his nurse, Gerda.

Part Two is called “Letters and Life.” In this section Stephen recovers from a horrendous accident which occurs at the end of Part One, in which he is hit by a truck (described rather ethereally with little blood or pain). In this new milieu of body casts and long, empty days of convalescence, Monk untangles his life for the reader (often by way of letters he has saved): he flashes back to the life with his first wife, Elizabeth, a famous author, older than Stephen by twelve years, and how she dies. All of this section takes place in his family home in Pennsylvania which his aunt manages. He also describes an early episode in his married life with Elizabeth in which a younger man inveigles him into having a brief and unsatisfactory affair.

In Part Three, “A Beginning,” the reader is brought back to the beginning time period where Stephen’s body is healed, and he ties up all the loose ends of the story. Stephen and his ex-wife Jane have lunch, and the reader finally learns what really happens in the beginning with her and the man she’s with in bed (actually, it’s a large children’s playhouse in the back yard where a party is being given). For some readers (even to Isherwood as a younger man), the novel might conclude a bit sappily, a bit too neatly. The ending is perhaps saved by the witty repartee the couple exchange. For twenty-first century readers, however, it may be a bit too sweet.

A few nuggets from the novel:

In this passage we read a portion of a letter written by Elizabeth, with regard to Hitler’s rise to power, while she lives in Europe: “Oughtn’t I to be doing something to try to stop the spread of this hate-disease? Oughtn’t I to be attacking it directly? But, of course, this very feeling of guilt and inadequacy is really a symptom of the disease itself. The disease is trying to paralyze you into complete inaction, so it makes you drop your own work and attempt to fight it in some apparently practical way, which is unpractical for you because you aren’t equipped for it—and so you end frustrated and doing nothing” (171). It may remind some of us of how we and the media are paralyzed by a particular presidential candidate at the moment.

“Suddenly, I didn’t care any more. The problem had dissolved itself in the beer; and now there wasn’t any problem at all, no drama, no tenseness. This was all clean fun, I told myself; and it didn’t have to be anything more than that.

In the darkness I remembered the adolescent, half-angry pleasure of wrestling with boys at school. And then, later, there was a going even further back, into the nursery sleep of childhood with it teddy bear, or of puppies or kittens in a basket, wanting only the warmness of anybody” (194). Here, Stephen describes (barely referring to it) his sexual experience with a young man. It helps him, a heterosexual man, to rationalize his one-night stand, a move rather dated by standards of contemporary gay or straight fiction.

“This was the next day, in New York. Jane and I had met—for the first time since our divorce—to have cocktails and lunch at a hotel on Central Park; and I had finished telling her about the civilian ambulance unit in which I’d enlisted as a driver, to go to North Africa” (293-4). This passage makes me wonder why Isherwood chooses this kind of job for Stephen Monk, when Hemingway has selected it over twenty years earlier for his noted character, Frederic Henry, in A Farewell to Arms. Perhaps it is a common way for a civilian to become involved in a war effort.

“‘Well, thanks,” I grinned. ‘You aren’t looking any too repulsive yourself, right now’” (294). Isherwood does this occasionally, uses a speech attribution which is not really a synonym for the word “say”—a practice that may be acceptable in British publishing but one which American teachers of fiction abhor. Also, the remark itself seems rather a backhanded compliment given to a woman who has once been your wife.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed