A WRITER'S WIT |

My Book World

I'VE MADE IT MY GOAL to read the entire oeuvre of late British-American author, Christopher Isherwood, over a twelve-month period. This profile constitutes the twenty-second in a series of twenty-four.

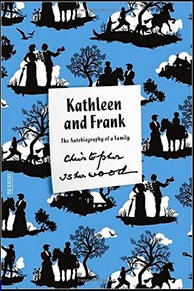

Kathleen and Frank makes the twenty-second book of Isherwood’s that I’ve read in about a year, and I thought perhaps that his work couldn’t get any better, that his best writing occurred when he was younger. But I was wrong. Mr. Isherwood, in his late sixties when he pens this book, distinguishes his latter years as a writer by undertaking, instead of fiction, nonfiction. In this tome of over 500 pages, he culls through letters that pass back and forth between his parents in the early part of the twentieth century, as well as his mother’s daily diaries. He then stitches them together in not only a seamless narrative about his parents’ courtship and marriage but a curiously interesting one, by inserting commentary or historical information from third sources. Even after having read all of Isherwood’s diaries, I believe he saves some intimate or startling details for this book.

In his previous works Isherwood’s parents always seem rather cardboardy, perhaps purposely, or perhaps because of a blind spot Isherwood has. In this book, one finds his mother, Kathleen, a very early feminist, one who sympathizes with the Suffragist movement in England. Not only that. She’s not really that keen on having children at an early age. She is well past thirty when she marries and nearly forty when she gives birth to Richard, Christopher’s younger brother by eight years. She is highly cultured, and very opinionated about any bit of theater that she’s seen or literature that she’s read. One can almost hear Christopher’s voice in hers or vice versa. At the same time, one might have thought that Christopher, as a gay man had a distant father, but if that were true it would have only been in the geographical sense. His father, Frank, was a soldier who fought with distinction in the Second Boer war in South Africa, and later died in World War I in France. Frank made a point of telling Kathleen that he didn’t wish to make Christopher conform to societal norms for being a boy; he preferred that Christopher make his own way. What a gift from a father to a son who is different. Frank, before he leaves for war, is also interested in the theater, so much so that he plays the piano, performs in certain kinds of musicals. But he isn’t a soft officer. He is a distinguished one, an officer whose men honor and respect him. His loss in 1915 is exaggerated by the fact that his body cannot be accounted for. Months pass before Kathleen gives up all hope, in fact, receives official notice from the Royal army.

There is a third character, one that is not present in most American family sagas. In fact, there are two additional characters: Marple Hall, the Bradshaw-Isherwood home, and Wyberslegh, the younger Isherwood home. Both are over three hundred years old at the time Isherwood writes. His vivid descriptions of both halls (he defines “hall” loosely as the home of the owner of a large estate) are not necessarily flattering. Of Wyberslegh he says that it is damp most of the year, and that may be the kindest thing he has to say. The upkeep and maintenance on a large residence is quite costly. Yet Wyberslegh is the home where Christopher lives until his father is stationed in Ireland and before he is sent to boarding school at a rather early age. It is the estate Christopher signs over to his brother Richard, when he realizes he is never returning to England to live—quite a generous act.

NEXT TIME: New Yorker Fiction 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed