A WRITER'S WIT

It is no simple matter to pause in the midst of one's maturity, when life is full of function, to examine what are the principles which control that functioning.

Pearl Buck

Born June 26, 1892

My Book World

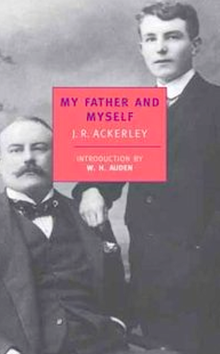

A few months ago, I profiled in my blog Ackerley’s novel, We Think the World of You, should you wish to see my rationale for reading this man in the first place. My Father and Myself is a memoir published posthumously. In its pages Ackerley outlines his suspicions about his father’s life before marrying his mother.

He begins by examining some photographs that document his father’s friendship with a number of other handsome young men back at the turn of the twentieth century. As one who embraces his homosexuality (with hundreds of partners over several decades), Ackerley sets about to see if he can discover if his father wasn’t also gay. What makes him suspect? Well, for one, unlike many British men, his father seems not to possess the usual homophobia but rather indicates to Ackerley that he has the freedom to pursue whatever life he wishes. And Ackerley feels compelled to take his father’s advice:

“I was now on the sexual map and proud of my place on it. I did not care for the word ‘homosexual’ or any label, but I stood among the men, not among the women. Girls I despised; vain, silly creatures, how could their smooth soft, bulbous bodies compare in attraction with the muscular beauty of men? Their place was the harem, from which they should never have been released; true love, equal and understanding love, occurred only between men. I saw myself therefore in the tradition of the Classic Greeks, surrounded and supported by all the famous homosexuals of history—one soon sorted them out—and in time I became something of a publicist for the rights of that love that dare not speak its name” (154-5).

The climax of the memoir may occur when Ackerley tells of searching out one of his father’s old buddies, one who is now near death. After heckling the elderly man with the question of whether his father may have liked men, he finally shouts at Ackerley, “Oh, lord, you’ll be the death of me! I think he did once say he’d had some sport with him [Count de Gallatin]. But me memory’s like a saucer with the bottom out” (262).

But Ackerley is still unsure. “May have” simply isn’t enough proof for him. The book is complete with an Appendix that dares to speak its name more graphically about Ackerley’s sexual difficulties. In all, the memoir is one of those fascinating books one should read: witty, devilish, and yet sad, too. Though Ackerley acts “freely” for his context, a dangerously homophobic England, he never quite achieves an approximation of happiness. One hopes that gay men never again have to live in such gloom anywhere on this earth. It simply isn’t fair.

NEXT TIME: NEW YORKER FICTION 2014

RSS Feed

RSS Feed