A WRITER'S WIT |

A Poet Remembered

Sheila Zamora, Soprano

Sheila Zamora, Soprano Perhaps the most memorable instance in which I accompanied Sheila Zamora was when she performed “Once Upon a Time,” a selection from a long-forgotten Broadway show, All American. She was a junior, and the spinet I played was shoved against the natatorium wall at South High in Wichita, Kansas. The smell of chlorine was nearly overwhelming, the edge of the spotlight barely illuminating my sheet music. While Sheila sang on behalf of what was called the Water Show, certain mermaids performed a synchronized swimming number. When the spectacle was over, a crowd in the stands applauded, and later Sheila drove me home.

I accompanied a number of vocalists in high school, college, and beyond. I followed and guided them all, but Sheila seemed more of a poet in her stylings than a mere soprano—I would seem to lean with her as she stretched a phrase or paused for a silence only she heard. One scorching summer day, while we were both in college, I ran into her downtown, near the old Henry’s store. In the crosswalk, we stopped to talk until any further exchange became impossible. I never saw her again.

Many years later, while perusing a publisher’s catalog, I ran across an ad for books of poetry. There, in print, I saw her name, Sheila Zamora, but was it my Sheila Zamora? In this book of poetry, the one I ordered out of great curiosity, the editor begins with a short biography. She reveals that Sheila, of Mexican-German parents, grew up in Wichita, Kansas, and graduated, in 1970, from Wichita State University with a BA in English. This Sheila had also married a man fourteen years her senior, had given birth to two sons, and eventually was accepted into a graduate program in creative writing at Arizona State. This Sheila's marriage later went sour, in fact, became untenable and dangerous. In 1978, when the Sheila I'd accompanied was thirty-one, her estranged husband, within view of her two boys, shot her four times and killed her.

*

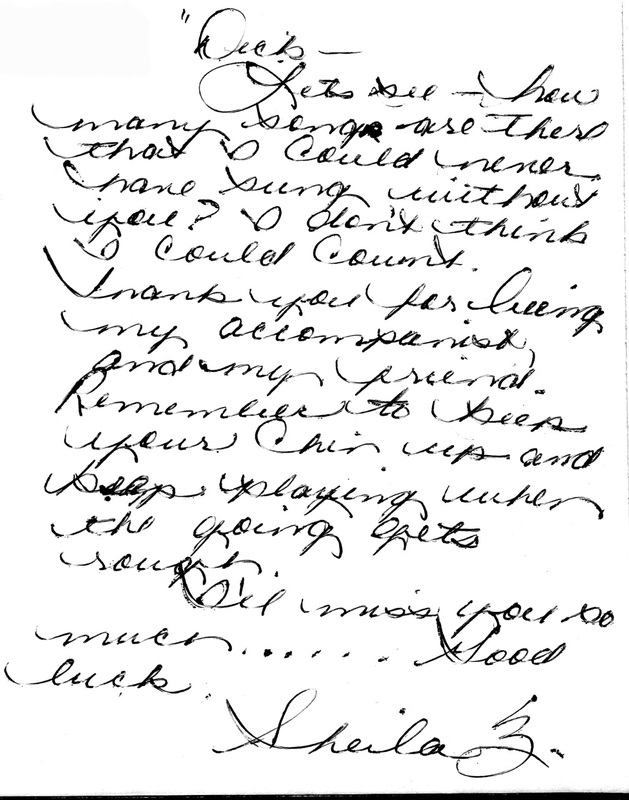

“Dick, let’s see,” Sheila writes in my 1965 yearbook:

“How many songs are there that I could never have sung without you? I don’t think I could count. Thank you for being my accompanist, and my friend.” Then on what becomes a more poignant note, she ends by saying, “Remember to keep your chin up and keep playing when the going gets tough. I’ll miss you so much . . . . Good luck. Sheila Z.”

I’ve read Sheila’s collection a number of times. As fine as they are, her poems may not be of equal maturation, having been frozen before the poet, no doubt, could reach her full potential. Still, I keep re-reading them, perhaps searching for the high school girl I once knew, the one who, if she had lived, might now be singing “Once Upon a Time” in a lower key, with a huskier voice, from the viewpoint of a mature woman. On this, the anniversary of Sheila's birth, I share below the entire poem from which today's "A Writer's Wit" is excerpted—one that exhibits how she may have wrestled with an idea of the man who took her life.

The Talk of Two Women

for Dina

the Wandering Jew in an opposite

direction from where it has leaned

toward the light, find in the deep

glossy purple of underleaves

the underside of words. I ask

to see your sculpture and you

meet my two small sons who are suddenly

between us as in a photograph taken years ago; it

barely distinguishes their arms, the color

of desert earth, or strands

of their hair like the startled

meticulous patterns of ceramic. We compare

our lives, using language

which is a second language, intangible

as instinct. I care most

for the hollows inside

your bottle-hangings where I imagine

breath might swirl, and you

listen to the breath shaped like woodwinds

inside my poems. We share

what we know about fear, about the obvious

risks of loving

men we can’t resist, their arms,

the gentle rafts where we would drown

while the real dangers

wait inside what we rarely trust: other women,

ourselves, and the sound of children

weaving through our voices. Yet

we find ways to talk, touching lightly,

as instinct turns us in other directions

from where we lean apart. We turn

toward the polish of art

or chairs

shaped like violins twisting us

from the idea of risk

into a mutual light.

Zamora, Sheila. Leaf’s Boundary. With an introduction by Pamela

Stewart. New York: Hoffstadt and Sons, 1980, 6-7.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed